Blog Post < Previous | Next >

CVP

Paradigm Shift - Part VI: New Hope for Affordable Housing?

We find ourselves bombarded these day by the one-sided argument that affordability all comes down to housing “supply and demand,” despite no statistical evidence that this is how housing affordability actually works. Consider that builders now have the largest inventory of unsold homes (excess supply) since 2009, even though housing prices have risen dramatically since then.

Shouldn’t we stop to ask why? Perhaps academics and housing “experts” are looking at the wrong end of the horse.

What if the “housing crisis,” defined as the number of existing homes minus the number of people wanting a home, is actually a symptom of more fundamental imbalances? What if the drivers of housing affordability are the supply and demand of something else?

The problem with distilling housing affordability down to overly simplistic, supply and demand housing "unit" data is that it overlooks underlying “costs” of real estate development. As it is, "housing costs” are only discussed in terms of how high prices are in order to argue for more bonds, taxes, and fees to fund public subsidies or to argue for more removal of local control of zoning and planning regulations.

According to the currently fashionable theory, more public debt and deregulation will allow for-profit real estate developers to make more money so they can provide more “affordable” units in their projects, which turn out to be a pittance: as little as 10%. This giveaway is also accompanied by offering huge density bonuses and endless “waivers” and “concessions” of local building standards so they can maximize profits even more (and the private equity crowd in New York is laughing all the way to the bank).

However, the important deterministic forces underneath housing pricing are (1) a “supply” of relatively inexpensive money (the cost of credit, private capital, mortgages, construction loans, etc.) on one side and (2) the “demand” for housing by well-paid workers, who make enough money to afford to buy or rent a home, on the other. But the inflation-adjusted income and higher wage opportunities for the average American working family have been going down for more than 45 years, and the cost of money is now going up (and looks to stay elevated), making buying or renting much more challenging.

(The low interest rates that the Federal Reserve kept artificially low for more than a decade in response to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, must now be paid for with higher rates to control stubborn inflation.)

Since neither interest rate levels nor the availability of higher paying jobs have ever been within the government’s or even private industry’s ability to control, this leaves us with only one other place to look for relief. Maybe, the question we should be asking ourselves right now is, how can we dramatically reduce the construction costs of home building?

The costs of labor and materials have nothing to do with local planning and zoning and are only indirectly related to other development costs, such as land costs, financing costs, the number of units allowed per acre, etc. They are more related to the overall state of the economy.

As such, the most reliable way to reduce housing construction costs and avoid economic imbalances -- to simultaneously keep interest rates at reasonable levels and to increase wages for the average American worker without causing a recession or increasing inflation -- is to increase productivity (producing homes less expensively).

Until productivity in housing design, development, and construction is increased (primarily through design innovations and new construction materials and methods), Adam Smith’s “invisible hand of markets” will continue to dictate the affordability of money, goods, and housing, regardless of what the ‘lost in the sauce’ politicians in Sacramento think should happen.

There’s an old joke in the construction industry about talking with clients: “I can build it for you faster, cheaper, or better, but you can only have two of these.” But what if technological innovations could allow us to have all three and do so profitably, at a smaller scale than previously thought possible?

The Holy Grail of affordable housing development would be to find a financially feasible way to capitalize on the ubiquitous opportunities to build and operate smaller, lower-density, infill, mixed-use, multifamily housing (under 35 units) in suburban communities. In places like Marin County, there are dozens of small opportunity sites for every large opportunity site capable of supporting a large project (more than 150 units) that a big developer would prefer to build and investment bankers like to finance.

Digital Magic

In the early 1980s, a Marin County startup named AutoDesk invented a computer-aided design (CAD) software called “AutoCAD.” Although the origins of CAD traced back to the late 1950s,[1] AutoCAD was the first affordable, mass-marketed product available for architects, engineers, and designers. It digitized the labor of creating architectural drawings and renderings by hand the same way WORD digitized writing a letter.

Its success coincided with the ubiquity of personal computers and by March 1986, AutoCAD had become the most widely used design application software in the world -- a position AutoCAD and the AutoDesk Design Suite of design software products still hold today.[2]

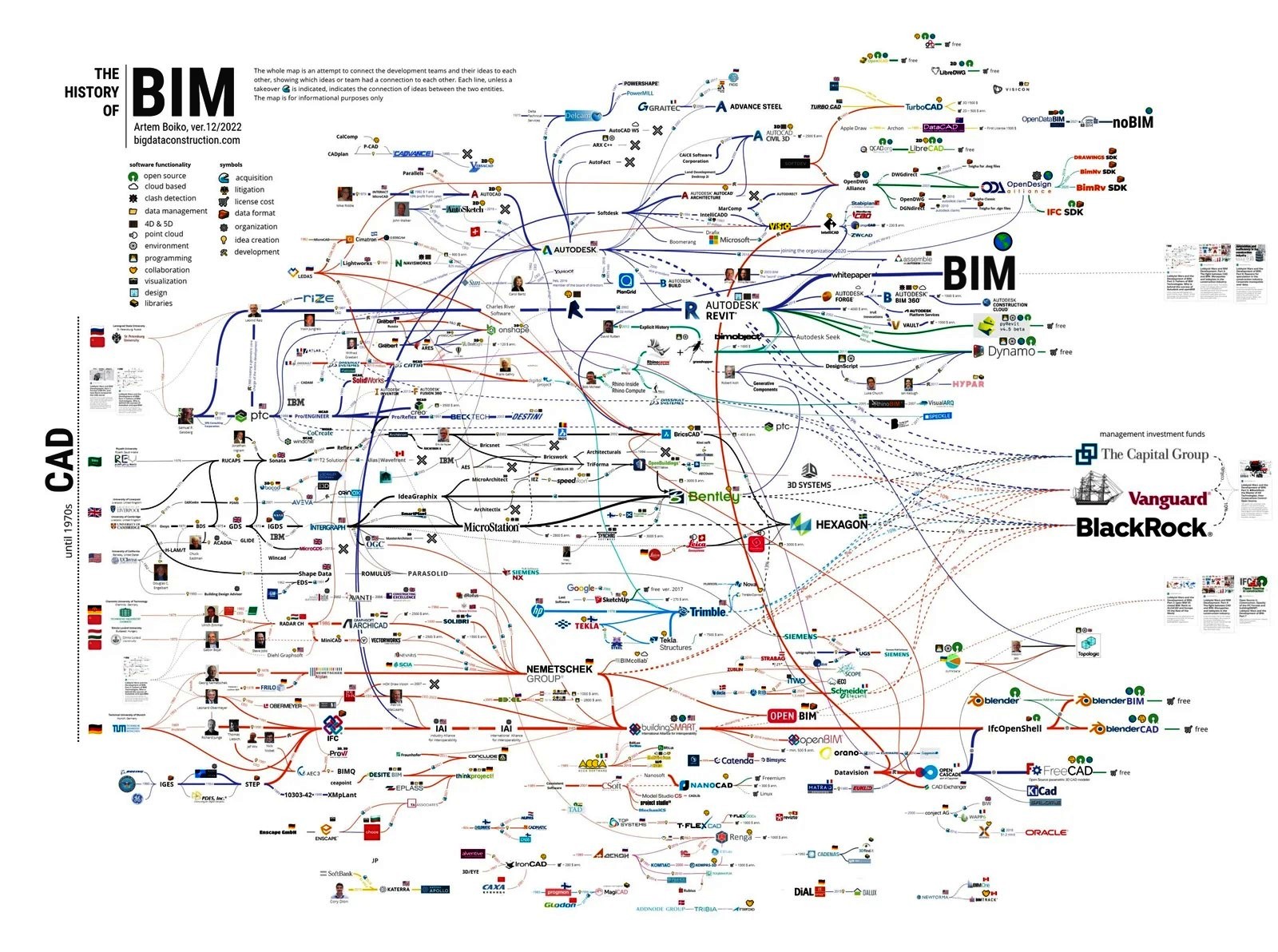

Since then, design software for the architecture, engineering, and the construction industry (AEC) has rapidly evolved from Computer-Aided Design (CAD) to parametric design software and Building Information Modeling/Management (BIM) software.

The diagram below depicts the expanding universe of digital design and modeling tools that have arisen since the birth of CAD.

Click on the image to enlarge

BIM Software built on CAD in the late 1980s and early 1990s, offers a comprehensive approach to building design and project management. It incorporates the building design’s geometry and spatial relationships with the quantities and properties of the materials used, location characteristics, and the construction management and on-site coordination challenges.[3]

For example, when an architect draws a wall using Autodesk’s Revit software,[4] a BIM program, it not only records the building’s design but also how that wall is built, what materials are used to build it (i.e., concrete, bricks and mortar, wood studs and drywall, etc.), and its related costs data, from which it can produce construction cost estimates and facilitate equipment and materials ordering and coordinate project construction logistics and scheduling. It enables better collaboration and project management across different disciplines in the construction industry.

Parametric modeling software enables and enhances CAD and BIM and frees the designer’s imagination. It allows rapid, multi-level design iteration by remote teams of professionals and the simultaneous exploration and comparison of multiple design options. It allows architects almost unlimited creativity [5] to create designs based on parameters and rules chosen by the architect rather than fixed dimensions and rigid geometries. This includes specific things like massing concepts, material choices, code requirements, and conceptual design variables that affect the style and expression of building elements.

The Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, by Frank Gehry Partners, with its unique structural shapes and sizes and exterior cladding of thousands of uniquely shaped metal panels, is a good example of the design freedom that can result from working in a Parametric/BIM digital environment.

Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, Frank Gehry Partners

Gehry said that his design of the Disney Concert Hall was partially inspired by the sails of sailboats. Using state-of-the-art-technology, he has become famous for turning whimsical ideas into metal and glass realities, such as the Hotel Marqués de Riscal in Spain.

Marriot

And then there is generative AI.

Generative AI, Design, and Construction

As everyone knows by now, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is based on the invention of Large Language Models (LLMs, also referring to Large Learning Models), the most ubiquitous of which currently being CHAT-GPT. But there are now dozens of LLMs available -- with names like OpenAI, Llama, GPT-4, Orca, Claude, Bert, and Megatgron-Core -- each capable of being “trained” on whatever information (data) is desired.

Since the initial public release of CHAT-GPT, less than 2 years ago, available AI applications have expanded far beyond generating text responses, simple searches, mathematical problem solving, or cheating on your homework, into medical and scientific research, psychology, imagery, and video, and architecture, design, and construction.

Generative AI allows the “prompter” (the term for the person(s) interacting with the AI) to iterate endless outcomes based on text or spoken inputs. These might be things like asking the AI to suggest alternative solutions to a building’s shape and form, to optimize a building’s design for passive solar energy gain, to protect the building from regional weather-related impacts, or to reduce the embedded carbon and lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of its construction materials and methods… or anything else one might want to imagine.

But AI architectural applications go beyond practical or physical parameters. It can iterate variations based on conceptual themes, stylistic preferences, and aspirational, abstract ideas.

The work of the offices of Zaha Hadid offers stunning examples of that.

Rublyovo-Arkhangelskoye, Russia, Zaha Hadid

But can generative AI help us develop more livable and humane housing and allow unlimited design customization, while utilizing modular, factory-built components that reduce construction time and building costs?

And if so, exactly how will that work?

NEXT - Faster, Cheaper, Better

[1] In 1957, Dr. Patrick J. Hanratty developed PRONTO, which is considered by many to be the first commercial numerical-control programming system.

[2] https://www.scan2cad.com/blog/tips/autocad-brief-history/

[3] https://www.scan2cad.com/blog/cad/cad-vs-bim/

[4] https://www.autodesk.com/solutions/revit-vs-autocad

[5] https://www.sculpteo.com/en/3d-learning-hub/3d-printing-software/the-best-parametric-modeling-software/

For more, see;

Paradigm Shift: Rethinking Housing Affordability

Paradigm Shift - Part II: Housing Unaffordability May Be Just Beginning

Paradigm Shift - Part III: How Affordable Housing Need Powered the Modernist Movement

Paradigm Shift – Part IV: The Assault on the American Dream

Paradigm Shift - Part V: Automation and AI, Double-edged Swords for the Housing Industry

Paradigm Shift - Part VII: Faster, Cheaper, Better

Paradigm Shift - Part VIII: Gen-AI Can Reduce Housing Costs

Paradigm Shift – Part IX: Gen-AI and Factory Built Affordable Housing