Blog Post < Previous | Next >

CVP

Paradigm Shift - Part V: Automation and AI, Double-edged Swords for the Housing Industry

Hardly a day goes by without hearing about artificial intelligence (AI): how it will take our jobs and take over the world. The rate of change in our lives feels like it’s getting faster. However, by and large, the housing construction industry is failing to adapt.

For hundreds of years, people have trekked to a plot of land to build a house. Materials and tools have been hauled by horse-drawn wagon and unloaded from trucks at the site, then the workers set about to construct a home, by hand, piece by piece. And although we now have amazing new materials, fancy battery-powered tools, lunch trucks, and Port-A-Potties, nothing about the home-building process has fundamentally changed.

Other than a few commonly available prefabricated items like roof trusses, most of the cutting, nailing, bolting, and assembly of materials is done on-site, rain or shine. The process is slow and fraught with delivery snags, weather delays, high labor costs, and all manner of unforeseen challenges. There are time-consuming inspections and labor protection precautions and endless contingencies. And, in a business where time is money and cost-overruns are the death of profits, this encourages mindless, design repetition to cut costs.

The result is a cityscape dotted with “affordable housing” projects that stick out like sore thumbs with the unique distinction of looking awful no matter where you put them. (But, we’re no longer allowed to protest, so long as our city is meeting its “RHNA housing quota,” handed down by the proselytizing minions at the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) in Sacramento).

What we build and the way we build housing is simply too slow, too inflexible, too wasteful, too inefficient, and too costly. This is resulting in profoundly negative consequences for environmental sustainability.[1]

And in a world where housing prices and affordability are determined by so many constantly changing outside factors, reducing the costs of construction may be the only sure-fire way to create affordable housing.

The Nature of Change

Scientific and technological advancements throughout history have always been disruptive, seem to come out of the blue, and are met with resistance and skepticism. As the saying goes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.[2]

As far as we know, hominids have been making and using tools (technology) for at least 3 1/2 million years and probably longer. (The oldest known site, so far, where stone tools -- sharp flakes of stone, hammers, and anvils -- were discovered is Lomekwi 3, located in northwestern Kenya.) Our tools have been a major driver of change throughout history and more often than not, in unexpected ways.

The transistor was invented in 1947. The first mainframe computers were invented in the 1950s. The integrated circuit was invented in 1959. Twenty years later, desktops with a hundred times the computing power were showing up in homes and offices. Twenty years after that, a hundred times the computing power was in the palm of your hand.

Who would have guessed that such rudimentary inventions would have such profound consequences?

Ten years ago, everyone said that the best thing to learn was how to code because you were guaranteed a great job. Today, coders are quickly going the way of buggy whip makers as AI’s coding capabilities are growing exponentially. At the same time, people seem to be yearning for an easier time in the past that, unfortunately, never really existed (which is why people have always been inventing new machines and technology to make life better and easier).

For my money, the benefits of scientific and technological innovation outweigh the downsides and abuses. Medicines and vaccines beat bloodletting and leeches, every day of the week. AI enables me to research articles 1,000 percent faster than before. This is a good thing. Automation and mass production make just about everything we buy, eat, and wear available at a more affordable price, and that’s a great thing.

Yes, of course, we have to curtail abuses and protect personal privacy and national security and all other important considerations. But, let's consider the positive potential for a moment.

If you disagree, maybe just stop reading now and go out in the backyard and start digging a hole to put your head in. You have a lot of company.

Resistance to Change

In the fall of 2024, dockworkers at major U.S. ports began threatening to strike to stop “automation” at our nation’s largest ports. They are convinced that robots and AI will result in massive job losses. I would suggest that they are on the wrong side of history.

Consider the case of the Netherlands.

In the early 1500s, Portugal dominated the international spice trade with the Far East. Amsterdam was just a small city of little international significance. Portugal controlled the key maritime trading routes and strategic ports along the route around the Cape of Good Hope to the ports in the Far East.

The Netherlands’ trading was mostly confined to short trips on smaller ships in the Baltic Sea. Yet, less than a century later, the Dutch had emerged as a major, seafaring power in Far East spice trading, surpassing both Portugal and England.

Initially, the Dutch had a problem. They didn’t have many seafaring ships. And they needed lots of them, as quickly as possible. But the primary driver of their fortune came from an unlikely source.

In 1593, a Dutch grain merchant named Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest patented a windmill-powered sawmill by developing a basic version of the crankshaft (like the one that drives the pistons in an internal combustion engine). It turned the circular motion of the windmill into vertical motion that drove rows of vertical saw blades up and down, which turned a tree trunk fed into it into flat boards used for shipbuilding. It sped up the log-to-lumber manufacturing process 30 times faster than sawing by hand and its measurements were far more accurate.

In addition to saving time and labor, this automated, mass production technology enabled standardized construction methods and allowed for faster assembly and lighter and narrower hull designs that made Dutch ships faster and more maneuverable, giving its ships an unassailable advantage. Shipyards became more productive and better organized, which ultimately increased the efficiency of shipbuilding and trade by 3,000 percent.

The Dutch rapidly expanded their maritime explorations, spanning Asia, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic, and by 1670 their merchant marine trade totaled 568,000 tons of shipping—about half Europe’s total.

Predictably, shipbuilding workers protested vehemently against van Uitgeest’s invention and threatened to strike to stop its adoption. They were concerned that handsaw operators would be out of a job. They considered “automation” to be a curse. Yet, a century later, the Netherlands dominated the world in advanced shipbuilding -- Amsterdam had become a major international trading center and industry-related employment had increased a hundred-fold.

Today, according to the CPPI 2023 report, no major U.S. seaport ranks in the top 50 of the global rankings for efficiency and competitiveness. U.S. ports need to make substantial investments in infrastructure, technology, and operational practices as soon as possible because they are becoming as obsolete as the jobs its dockworkers are presently trained for.

The housing construction industry now finds itself in the same “boat,” so to speak. Like the Dutch and their need for ships, incremental improvements are not going to cut it.

The industry needs a “sea-change” …and soon.

California housing policies defend the status quo

The most stalwart financial supporters of California politicians who have led the charge to create California’s dysfunctional housing laws have been the construction trades unions. Like the dockworkers and their brethren, five centuries ago, these constituencies appear to see no benefit in progress, increased efficiency, lowering the costs of construction, or reducing the climate impacts of what and how we build (At least, I've yet to see any proposals for automation come from them.). On the contrary, their interests appear to lie in preserving status quo jobs, while increasing wages and benefits.

As such, I would suggest they and all the politicians they support are also on the wrong side of history. Unfortunately, however, the holes they are digging are not just impacting their futures but all of ours, as well.

This is not to say construction tradespeople are bad people or that there is some kind of conspiracy afoot. Those who work in the trades are some of the most honest, hardworking people I’ve ever met. Their failing is that they are just being all too human, like the rest of us: instinctually shortsighted and self-interested to a fault. But, at least they’re not hypocrites like the politicians and movers and shakers who are all too happy to take their money but offer them no policy alternatives, in return.

All those glad-handing, Sacramento politicians suffer from a profound lack of vision and the trend is not the working man’s friend.

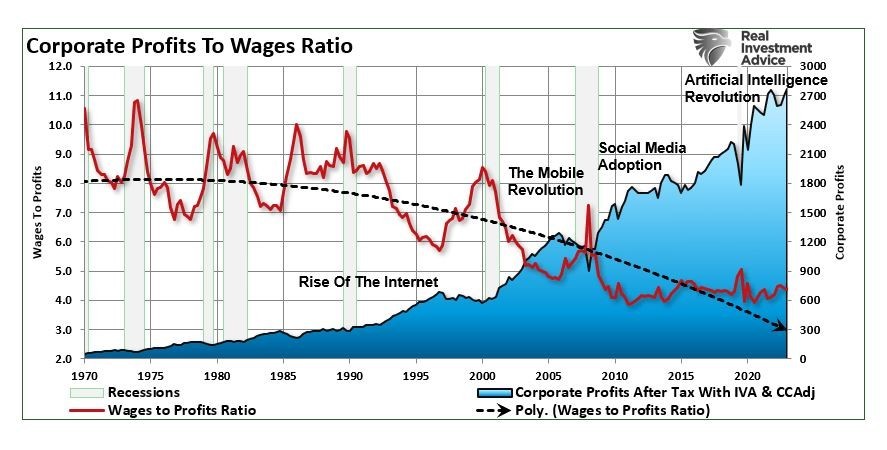

The chart below is instructive. It shows the relationship between corporate profits and the wages they pay to achieve them. Notice that as they reduce the need for workers through the adoption of new technologies, and wage costs fall, their profits continue to grow, even accelerate. Increased productivity is the most essential component of non-inflationary, economic growth and can be wealth-building for all involved.

That’s something we need more of, today, not less of.

Being a Luddite won’t change this. Since the invention of the wheel, for better and for worse, no government or special interest groups have ever been able to control the inevitable outcomes of technological innovation any more than we can now control automation or AI.

The impacts of automation and AI on jobs

Fifty years ago, a person could still pursue an occupation in a field that his father and even his grandfather before him had pursued, but no longer. What we define as a “job” is now undergoing irreversible change.

An analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute, entitled, “Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages,” predicts that due to the integration of AI and robotics,

“…demand for high-skill workers will rise, particularly in healthcare and STEM-related professions. At the same time, demand for workers in occupations such as office staff, production workers, and customer service representatives will [dramatically] decline. Automation, supported by generative AI (gen AI) tools have the potential to automate work activities that absorb up to 70 percent of employees’ time today.” [Emphasis added]

In another study, “The future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills,” the authors predict that

“By 2030, up to 30 percent of current hours worked could be automated, accelerated by generative AI. Occupations with lower wages are likely to see reductions in demand, and workers will need to acquire new skills to transition to better-paying work.” [Emphasis added]

However, McKinsey also predicts that AI will not only create jobs but will also create economic surpluses that enable businesses to pay for workforce job transitions. As such,

“Faced with the scale of worker transitions we have described, one reaction could be to try to slow the pace and scope of adoption in an attempt to preserve the status quo. But this would be a mistake. Although slower adoption might limit the scale of workforce transitions, it would curtail the contributions that these technologies make to business dynamism and economic growth.” [Emphasis added]

And,

“Providing job retraining and enabling individuals to learn marketable new skills throughout their lifetime will be a critical challenge. Beyond retraining, a range of policies can help, including unemployment insurance, public assistance in finding work, and portable benefits that follow workers between jobs.” [Emphasis added]

In the housing industry, automation and AI will undoubtedly be double-edged swords slicing their way through the entire design and construction process. (Part VI will discuss how.) Many jobs and methods will become obsolete. Other jobs will emerge and pay twice as much.

Prefabrication, componentized construction, off-site assembly, and other innovations will continue to be highly disruptive, save time and money, increase worker safety and construction efficiency, and replace traditional methods. The growth of advanced automation methods and AI construction management will turbo-charge that trend.

Recognizing this and helping the workforce adapt to and participate in the positive outcomes is the only way forward. When it comes to affordable housing needs, the future can’t happen soon enough.

[1] The World Economic Forum estimates that “buildings are responsible for 40 of energy consumption,” and this is just from daily operations and doesn’t include the environmental destruction and externalities from building materials sourcing and construction.

[2] French critic, journalist, and novelist Alphonse Karr in 1849.

For more, see;

Paradigm Shift: Rethinking Housing Affordability

Paradigm Shift - Part II: Housing Unaffordability May Be Just Beginning

Paradigm Shift - Part III: How Affordable Housing Need Powered the Modernist Movement

Paradigm Shift – Part IV: The Assault on the American Dream

Paradigm Shift - Part VI: New Hope for Affordable Housing?

Paradigm Shift - Part VII: Faster, Cheaper, Better

Paradigm Shift - Part VIII: Gen-AI Can Reduce Housing Costs

Paradigm Shift – Part IX: Gen-AI and Factory Built Affordable Housing