Blog Post < Previous | Next >

CVP

Paradigm Shift - Part VII: Faster, Cheaper, Better

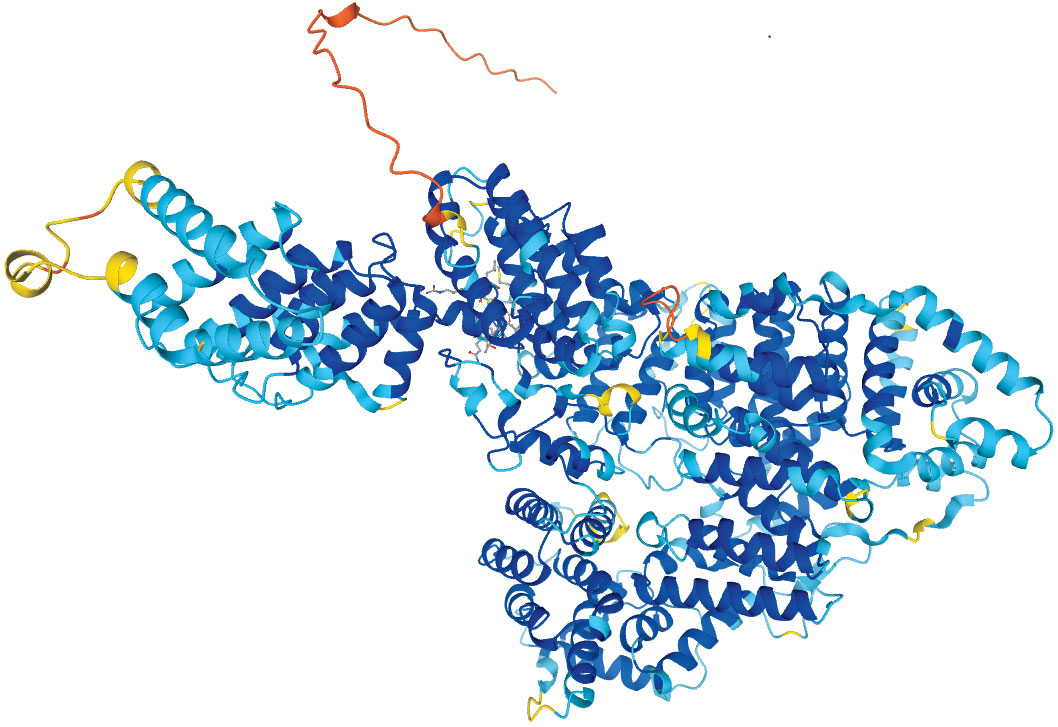

Proteins are the building blocks of life. They’re made up of chains of amino acids folded into complex shapes, which determine their function. Understanding the structures of proteins and how they interact is fundamental to understanding all forms of life.

Scientists have been trying to determine the structures of proteins since the 19th Century. In the past 50 years, using advanced techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance, cryo-electron microscopy, and painstakingly crunching genetic codes, scientists had figured out the structures of approximately 180,000 proteins.

In 2022, Google announced that its “AlphaFold AI” at DeepMind Labs had accurately deciphered the structure of over 200 million proteins – essentially every protein in the known universe – virtually in the blink of an eye. The potential impacts of this quantum leap on medical, technological, and scientific breakthroughs are unfathomable.

I realize we are so overloaded hearing about “AI” that our eyes glaze over at the mention of it. But AI really matters… and it’s going to change everything… and soon.

In Paradigm Shift - Part III: How Affordable Housing Need Powered the Modernist Movement, it noted that we find ourselves in a situation similar to the modernists of the early 20th Century, searching for a way to mass produce quality, affordable housing faster and less expensively. The Modernists believed that new technology was the only thing capable of helping them do that.

Factory-Built

Aside from having new power tools and equipment, we still build the typical single-family home or small, infill multifamily project the same we did 100 years ago: workmen do manual labor using materials delivered to a building site, rain or shine.

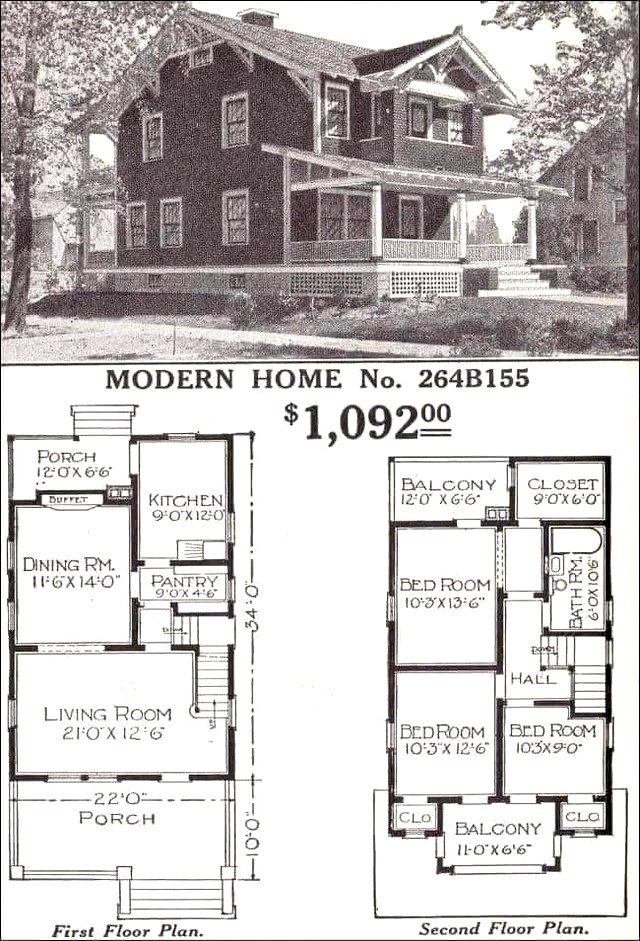

That’s not to say people haven’t tried to change that. In the 1930s, Sears Roebuck and Co. published a housing catalog (click this link) of build-it-yourself houses. They sold homes the way IKEA sells furniture.

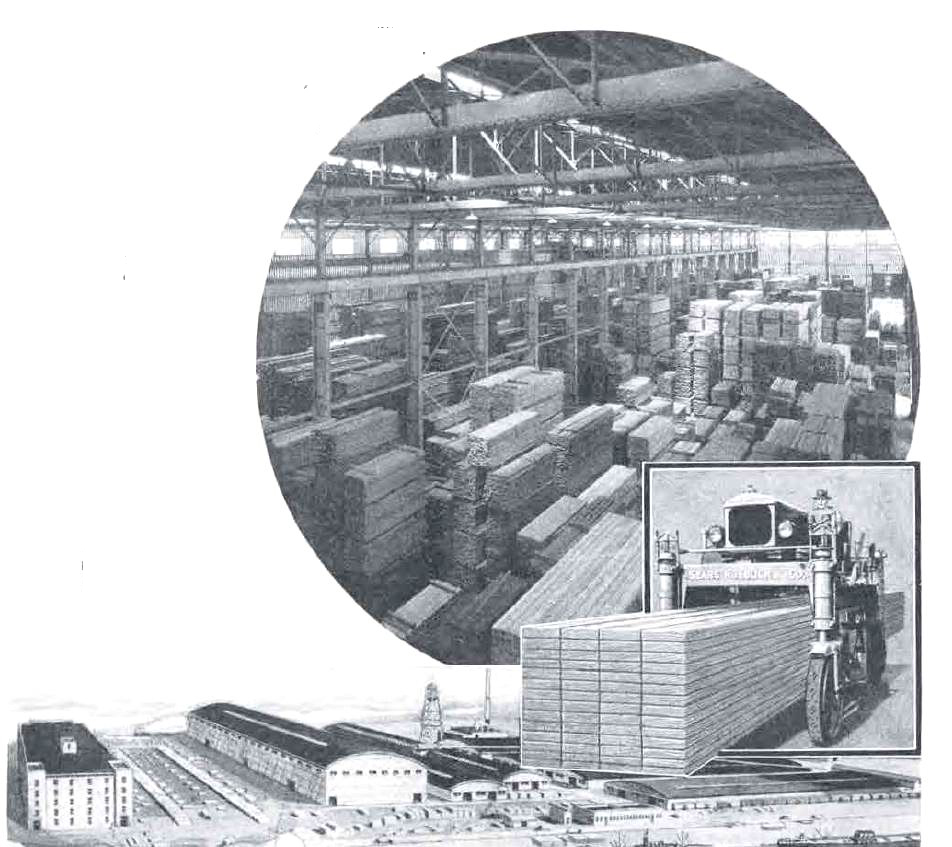

Its “mass production” factories in Newark, New Jersey, and Chicago, Illinois, using the most “modern machinery,” would ship you plans, instructions, and everything you needed to build your new home, in a disassembled, precut kit that included lumber, siding, windows, roofing shingles, plumbing fixtures, appliances, cabinetry, and stair railings, down to the last screw and nail.

Sears Roebuck Catalog

Sears marketed their “Honor-Bilt Homes” brand this way since 1900 and by 1930, they claimed to have sold over one hundred thousand of them. The house below would have set you back $1,092, shipping included.

Decades later, “factory-built” evolved into “modular homes,” where completed parts of a house, built in a factory, are delivered to the building site and “stitched” together. This method has been most commonly used to build “single-wide” and “double-wide” mobile homes, since the 1950s.

Mobile homes are basic, affordable housing. The manufacturers, who tend to be regional, keep prices lower than conventional construction by offering a limited number of models and using inexpensive materials, and the units can be delivered by trailer truck on a standard width lane on the highway (typically flagged as a "Wide-Load").

Modular construction is now also used to build higher-density, multifamily housing. These are configurations of rectangular, shipping container-sized units (and sometimes actual refitted shipping containers) stacked and stitched together on prefabricated steel frames, erected on the site.

“Hope on Alvarado,” shown below, is a proposed 84-unit shipping-container project to house the homeless in Los Angeles, designed by KTGY Architecture + Planning.

The affordability and cost reductions of these projects are derived from the simplicity of construction, the use of repetitive unit designs, and ease of shipping: as shipping containers they can be transported by truck, rail, or boat.

The 223-unit, Mayfair apartments, built in El Cerrito, California, used wood-framed, rectangular units in various configurations. Again, this type of factory-built housing works best for larger projects.

Modular Building Institute

There are also factory-built, “modular” or “componentized” single-family housing, where prefabricated wall or roof panel components or entire sections of the home (bathroom, kitchen, etc.) are prefabricated, then assembled, on-site.

Huntington Homes

There are also many architects using prefabricated, modular construction to design custom, single-family residential, but they tend to be just as or more expensive than traditional, site-built homes.

OMD

However, factory-built housing has really come into its own with the boom in accessory dwelling units (ADUs). The majority of ADUs are either modular construction or shipped as fully completed units, dropped onto a site-built foundation with a crane.

Plant Prefab

These successes aside, however, although prefabricated building components are widely used for things like roof trusses, factory-built/modular housing has so far failed to have a major impact on mass-market, single-family and smaller, multifamily home building.

The Limitations of Factory-Built Housing

The limitations of factory-built housing are formidable in trying to address smaller, affordable, infill, multifamily projects. Most factory-built housing manufacturers can only serve customers within a limited distance from their plant. And the smaller the project, the more customized the unit designs, and the farther away it is, the less cost effective it becomes.

Other significant challenges to the prefabricated housing business are (a) pre-finished, modular units often need to be extensively over-designed, structurally, to tolerate the stresses of shipping (reducing cost savings), and (b) production lines configurations at facilities tend to be fixed and can only produce certain “models” at any given time.

Changing assembly line configurations to accommodate "one off," custom design requests can be expensive and is typically only done when new designs are introduced or the project is of sufficient scale to cover the costs.

For example, Factory OS is a major investment in housing prefabrication by Google, Autodesk, Citibank, Facebook, and Morgan Stanley, operating out of an old shipbuilding hanger on Mare Island near Vallejo, California. This facility was previously home to two prior, failed, modular housing manufacturing ventures.

Factory OS

Note the striking similarity of the manufacturing floor at Factory OS and the image of the Sears and Roebuck factory, above, 125 years earlier: fixed dimensional spaces, fixed assembly lines, producing limited types of housing components, using manual labor and hand tools (without robotics or flexible assembly line automation).

Not much has fundamentally changed.

Developers I know who have tried to work with Factory OS to build low-income, multifamily, housing projects have come away disappointed because they are too inflexible and could not deliver a product at a competitive cost compared to site-built construction. It's surprising that Autodesk, with its formidable position in the design and construction / CAD / BIM / Parametric software universe, would invest in such a venture.

All Businesses Are Now in The Data Business

The architecture and design business is rapidly transforming from a paper documents business to a responsive, real-time, BIM-enabled, digital data business that fast tracks designing, specifying, materials ordering, and project staging and management processes from the initial concept to the last brick, laid in place. Similar to Sears’ instructions kits, the profession’s data-driven tools now know everything needed to build a project, from the plans and specifications to the lumber, siding, windows, and roofing shingles to plumbing fixtures, appliances, cabinetry, and stair railings, down to the last screw and nail.

More importantly in the virtual world if a piece of the project’s three-dimensional puzzle needs to change, everything else automatically adjusts or lets you know if that change has caused conflicts with something else.

This is critically important because it’s not uncommon these days for architects, engineers, and designers to be still working on finalizing the construction documents for one part of a project while contractors are already building another part of the project… fast-tracking, under the pressure of tight deadlines.

The mantra of the construction industry is “time is money.”

As it stands, unless it's for a large project, factory-built housing production typically lacks the ability to address this dynamic. They can’t quickly address architects’, developers’, or clients’ needs for design changes and customization, on the fly, outside of predetermined options.

If modular, prefabricated housing is going to thrive, generative AI-enabled automation and robotics, and AI-assisted design, supply chain, production management, quality control, and workflow optimization will inevitably have to play a decisive role.

For more, see;

Paradigm Shift: Rethinking Housing Affordability

Paradigm Shift - Part II: Housing Unaffordability May Be Just Beginning

Paradigm Shift - Part III: How Affordable Housing Need Powered the Modernist Movement

Paradigm Shift – Part IV: The Assault on the American Dream

Paradigm Shift - Part V: Automation and AI, Double-edged Swords for the Housing Industry

Paradigm Shift - Part VI: New Hope for Affordable Housing?

Paradigm Shift - Part VIII: Gen-AI Can Reduce Housing Costs

Paradigm Shift – Part IX: Gen-AI and Factory Built Affordable Housing