Blog Post < Previous | Next >

CVP

Hold Onto Your Hats

Why every city and county in California will likely fail to meet its RHNA quota in the 2023-2031 housing cycle.

The New York Times recently published this graph in an article by Ben Casselman and Lauren Leatherby called, How is the Economy Doing? The chart compares economic activity over the past 3 months with economic trends that have been in place since 2010 to try to make sense of where we might be headed.

Despite the chart's earnest presentation of the data and the authors’ best efforts, it proves that trying to prognosticate anything these days is impossible. Or put another way, as legendary investor John Bogle said, “Nobody knows nothing,” which includes me too, but maybe we can try to make educated guesses.

Consider for a moment: The first six months of 2022 were the worst start of a year in the stock market’s history. In mid-June, the S&P 500 Index suffered three 90/90 down days in a row (90% of the stocks were down and 90% of the trading volume was down), the greatest number of 90/90 days in a row in stock market history. This all happened while the Federal Reserve claimed that the economy was strong, employment was strong, and consumers were in great shape. If that’s true it has never happened in stock market history, going back to the beginning of the Great Depression.

Strange days, indeed.

We had a once-in-a-100-year (we hope) pandemic that no one on the planet saw coming (except for science fiction writers). We had equally unforeseeable global lockdowns, dead-stopped economic activity, spent unprecedented trillions of dollars in government funds to support our economy, and had decision-makers frantically shooting in the dark.

We’ve had massive “quantitative easing” by the Federal Reserve (translation: holding interest rates artificially low and adding unsustainable debt to the central bank’s balance sheet) followed by a panicked Fed pivot to “quantitative tightening” (translation: the opposite, raising interest rates at one of the fastest paces in history and off-loading debt).

We’ve gone from being told, “We have to do all we can to save the economy” to “We have to do all we can to stop the economy” in less than a year.

The same central bankers who opened the floodgates to allow trillions of dollars to supercharge financial speculation of all kinds 2 years ago (ostensibly to avoid massive unemployment) are now hell-bent on destroying the economy (to intentionally drive up unemployment) in the belief that this is needed to “save” it. (Does it ever dawn on these guys that they can't control everything that's bad in the world with interest rates?)

The problem is that the majority of the inflation we are experiencing has less to do with interest rates than with the unprecedented pandemic, the war in Europe, and the resultant and equally unprecedented supply-chain/manufacturing disruptions around the world in every conceivable industry. Add to that increasingly impactful climate change-induced disasters (flooding, drought, endless wildfires, etc.) and you have to wonder if the Federal Reserve isn’t just “pushing on a string” or better, trying to do brain surgery with a sledgehammer.

The Fed is panicking about the mistake it made a year ago (too much financial stimulus for too long), seemingly oblivious to the mistakes it may be making now (too much tightening too fast). They are stumbling through our economy like a blind bull in a china shop.

On the one hand, they acknowledge that the outcomes of their actions will not be evident until six to nine months from now, while at the same time increasingly barking out shrill warnings in reaction to every little piece of “backward-looking” data that crosses the wires as if convinced they have to immediately get inflation down to a magical (and made up out of whole cloth) 2% rate as quickly as possible or the world will end.

Unfortunately, the Fed’s track record in predicting the future is abysmal. Or as noted financial analyst Gary Shilling recently commented,

“The Federal Reserve’s forward guidance program has been a disaster, so much so that it has strained the central bank’s credibility.”

Is everything going to return to “normal” in the near future? No one really knows, but what we do know for sure is that none of the inflation we’re experiencing was caused by the average working person—you know, those tax-paying people who keep the economy going-- yet they are the ones who are now being told they have to bear the burden to contain it. And forget the poor and disenfranchised in our society. The seven private bankers on the Federal Reserve Board only give lip-service of their existence and uses their "suffering" from inflation as an excuse.

There is something barbaric about our concept of how our economy is supposed to function. And more and more, it’s just not working for regular people. No wonder so many people are so pissed off these days. California's state housing policies are a corollary to this approach to problem-solving.

In the super data-dependent world we now live in, the data that our governments operate and act upon is archaic and manipulated and adjusted (e.g., the CPI) to the point that it’s hard to believe that any of it is reliable. But one of the clearest and loudest canaries in that coal mine is the housing market data. And, as short-term interest rates approach the cap rates investors are willing to pay to purchase and operate residential properties, investment in affordable housing looks even less attractive.

House of Cards

As I recently noted, homebuilder sentiment and housing starts are falling like a rock, the 30-year home mortgage rate has risen above 6%, and there’s renewed talk about mortgage origination companies going under (something we haven’t heard about since 2008). And despite the Federal Reserve’s rantings about the inflationary dangers of wage increases, real, inflation-adjusted wages continue to fall.

After spending years turning housing into a meme stock by providing artificially low-interest rates, the Federal Reserve decided that the health of the housing market should not be taken into consideration, even though we need to address our housing “affordability” challenges more than ever. And falling residential construction starts will not help lower rental rates no matter how high the Fed raises interest rates and, in fact, because of it.

Admittedly, it's a tough conundrum, but all this brings me back to my prediction that the state's housing quota system is about to fail, catastrophically, in the next housing cycle. No one will build enough units to meet their quota in the coming housing cycle, no matter how many penalties the state threatens or how high they set their housing quotas.

If one creates a college admissions exam and 100% of the students fail that exam, do you blame that on the students or do you blame the exam? That pretty much says it all about the California’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) quota allocation system. Every year, more and more cities and counties fail the test and that trend is about to speed up.

But more fundamentally, if the global economy continues on its trajectory into a broad-based recession, stagflation, or worse, what is the average working person or small business owner going to do this time around when there are no more foreclosure or rent moratoriums, no more PPP bailout checks, and no more trillion dollar fiscal stimulus programs?

Spoiler alert: nothing good because it's not just about what is happening now or next year, but economic downturns are like supertankers: once they head in a direction, it takes a long time to turn them back around. We are getting a bit too close to that tipping point, which does not portend good things for the housing market.

Despite the Federal Reserve’s soothing outlook, things are not okay and the “consumer” is not “strong.” (Household wealth suffered the biggest drop ever in the second quarter--the third quarter will be much worse.)

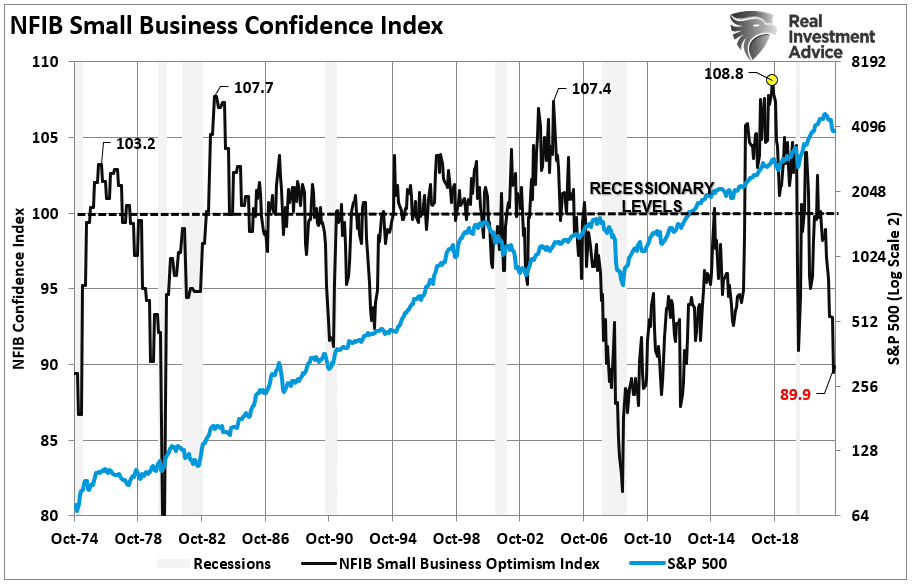

Now, consider this chart of the latest Small Business Confidence Index. We’re looking at negative sentiments we haven’t seen since 2008.

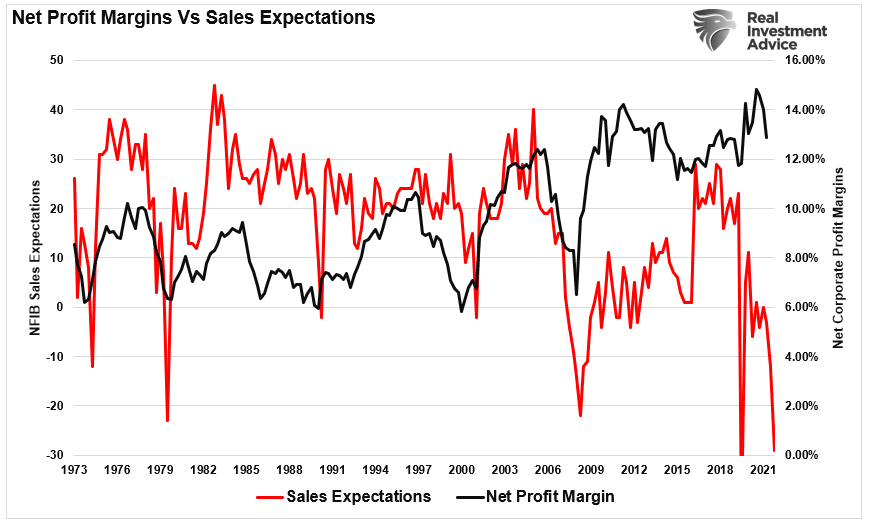

Or consider the Sales

Expectations of those same businesses. We’re looking at falling projections we’ve

only seen once in the past half-century.

Now, look at the Net

Profit Expectations from those sales. We’ve never seen such a dramatically

rapid fall since the outbreak of World War II.

Against this backdrop, we need ask ourselves, how sound are the finances of the average California city and county? How prepared are they for what may be coming?

Against this backdrop, we need ask ourselves, how sound are the finances of the average California city and county? How prepared are they for what may be coming?

There is no question that the ongoing juggernaut of state housing laws, designed to remove all local control of planning, zoning, and residential development, will lead to potentially overwhelming consequences for this local government. These would include but not be limited to,

An increase in lawsuits by developers and advocacy groups to demand high-density zoning, property tax exemptions, and waivers of impact fees,

An increase in local government’s operating expenses as their costs of goods and services and employee salaries and benefits continue to rise, and the demand for public services, schools, police, and fire protection continue to rise, and

An increase in local government’s costs for infrastructure improvements and maintenance (water, sewer, roads, etc.) to serve thousands of unplanned new residents.

And all this at a time when people are voting against taking on more public debt or raising taxes (California tax collections are falling) and have plenty of personal debt of their own.

The Fed and the State of California are making a huge error in assuming that the rise in household equity due to the past year's inflation (which becomes highly illiquid as interest rates rise[1]) is the equivalent of consumer health and buying power. The truth is the exact opposite.

Under these circumstances, an educated guess would be that our present path is more likely to lead to market gridlock, liquidations, and less affordable housing than more affordable housing. (Builders won’t build what they can’t rent or sell for a profit and people can’t rent or buy what they can’t afford or finance.)

As such, the state should be immediately funding cities and counties to help them build low-income housing (particularly small and medium-sized municipalities that are already running on fumes and have had to cut staff, public services, and operating hours to the bone) instead of layering on threats and penalties and the administrative cost burdens of more and more rules and procedures to get an “A” on their Housing Element certification report card.

The state’s legislative “piling on” combined with the Fed’s panicky actions are a recipe for future municipal debt defaults and bankruptcies. And once that trend begins, it has a rapid cascading effect on everyone and everything else (i.e., less and less residential development). And there is no question that the average city in the state of California is not prepared for this outcome.

Just an educated guess, but what if…?

[1] “We have had five months of zero M2 growth–money supply growth, and the Fed isn’t even looking at it,” economist Steve Hanke said recently in an interview with CNBC on Monday. “We’re going to have one whopper of a recession in 2023.”

Bob Silvestri is a Marin County resident, the Editor of the Marin Post, and the founder and president of Community Venture Partners, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit community organization funded by individuals and nonprofit donors. Please consider DONATING TO THE MARIN POST AND CVP to enable us to continue to work on behalf of California residents.