Blog Post < Previous | Next >

Mad Magazine - CVP

What now?

The previous article in this series, “Party On To the Apocalypse,” addressed the wholesale environmental degradation that our way of life is wrecking on the planet. This final part attempts to address what we can do about it. However, from the outset let me be perfectly clear, I have no magical answers and I make no claims, whatsoever, to know how to solve our predicament.

Even casual research produces troves of studies and proposals arguing every possible scenario. But the cumulative challenges we’re facing are way above my pay grade, and in fact, are way above any one person’s pay grade.

Addressing our combined social, economic, and “environmental deficit spending” is going to be a group undertaking. It won’t just take a village, it will take a global village to begin to get through this mess, unless, of course, one’s idea of the future is some Hollywood, dystopian scenario that includes a new form of feudalism, where the rich retreat to ranches in Montana and Hawaii, and live in heavily fortified enclaves, stockpiling gold, guns, and food, while everyone else lives in some kind of Blade Runner-like urbanism.

I recognize that there will be some who will say I shouldn’t complain unless I have solutions, which I do try to offer. But when the stakes are this high it’s okay to just play the role of Paul Revere. He may not have known how to win the war but he knew he should be warning people trouble was on the way.

Where to begin?

No one can say exactly what we need to do about the combined socioeconomic, democratic, and environmental challenges we are facing or in what order we need to do it. If anything, we need to fix everything simultaneously. All we know is that to continue to “party on” won’t get us there.

That said, perhaps there’s no one better to consult on this question than the original party animal, Albert Einstein.

Credit: Environmental Media Fund

Einstein said,

"If the facts don't fit the theory, change the facts."

No, he wasn't talking people who change the facts to suit their own purposes. He meant that if we want to get to the truth, we need to challenge our own assumptions… the so-called “facts.” So, perhaps we should start by questioning the unspoken assumptions that are driving our socioeconomic and environmental challenges.

Much has been made of technology’s ability to address environmental degradation. And, perhaps, if we can just slow our growth, technological innovations can catch up to address the problems. But this scenario seems increasingly unlikely and in its absence we’ve each taken it upon ourselves to try to “do something,” anything, individually.

Unfortunately, the changes needed are systemic, holistic, and involve government and corporate participation and funding prioritization at all levels. Worse still is that fact that we’ve started to lull ourselves into false securities about what can and cannot do, individually, to combat major challenges like climate change. But so far, these are essentially just ways to rationalize how we can continue to party on.

Individual efforts will be grossly insufficient.

Bjørn Lomborg, director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, recently wrote, in an opinion piece entitled, Your electric car and vegetarian diet are pointless virtue signaling in the fight against climate change,[1]

“Switch to energy-efficient light bulbs, wash your clothes in cold water, eat less meat, recycle more, and buy an electric car: We are being bombarded with instructions from climate campaigners, environmentalists and the media about the everyday steps we all must take to tackle climate change. Unfortunately, these appeals trivialize the challenge of global warming, and divert our attention from the huge technological and policy changes that are needed to combat it.”

And

“It is absurd for middle-class citizens in advanced economies to tell themselves that eating less steak or commuting in a Toyota Prius will rein in rising temperatures. To tackle global warming, we must make collective changes on an unprecedented scale.”

So, why do we delude ourselves in the face of problems rather than hunkering down and making the innovative changes and whatever short-term sacrifices are needed to solve them? The answers to that question are too long to even list and involve everything from personal psychology to the human condition, where our short lifespans inherently produce a myopic understanding of long-term consequences.

I think one of the more important reasons for our current situation, one that is rarely included in environmental conversations, is the foundational beliefs encoded into our socioeconomic system.

The Darwin Fallacy

I consider myself a capitalist. In fact, I think capitalism is essential to innovation and entrepreneurship. But like anything else, it only works if the users have a code of ethics and a strong sense of morality. Presently, Our form of capitalism is failing too many people to be sustainable.

No lesser individuals than Ray Dalio, the manager of Bridgewater Capital, the world’s largest hedge fund, and tech billionaire luminaries like Marc Benioff have recently come out and said that. They are saying capitalism, as we presently practice it, has to be radically altered or else those left out of its rewards will eventually take a blunt, public policy instrument, driven only by anger and frustration, and tear it apart.

The problem is not capitalism, per se, but like anything else, taken to its extreme, there are downsides. Our socioeconomic system has become overly reliant on a form of "hyper-capitalism" that is based on misguided beliefs about the benefits of constant, ruthless competition and catch phrases like “survival of the fittest,” which turn out to be a grossly simplistic way of understanding of what’s really going on.

Competition is great in theory and in sports, but in real life the most essential piece, a level playing field, doesn’t exist. Or as former senator Al Franken put it,

“They tell you in this country to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, but first you’ve gotta have the boots.”

Nature v Nurture

In the mid-1800s there were two competing theories about evolution, the theories of Charles Darwin and the theories of Jean Baptiste Lamarck.

Lamarck believed that what happened to an organism during its lifetime affected future generations and drove evolutionary changes. For example, Lamarck believed that the necks of giraffes grew longer, over time, because they stretched them, during their lives, to reach tree tops. Darwin, on the other hand, suggested that a mutation of some kind (he had no idea there were genes), which were the result of pure chance, caused their necks to grow longer, thus giving long-necked giraffes a competitive advantage over short-necked giraffes, and more access to food, so they “survived” and were, quite by chance, the “fittest.”

For Darwin, it was just happenstance that in some cases this worked out for the better and in other instances it might have led to extinction.

Lamarck’s theories were instinctively intriguing, but scientifically incorrect, and fell out of favor. But his curiosity about the impacts of our experiences (“nurture”) would prove to be more correct than he could have imagined. Darwinism, on the other hand, which could be considered a precursor to the science of genetics, became our widely-held belief. More importantly, it was the essential basis for the socioeconomic system we operate under today.

Unfortunately, Darwin’s theories have morphed into the mantra of modern hyper-capitalist society -- The so-called “dog eat dog” world. This has been the rationalization for some of the most brutal repression, violence, atrocities, inequality, and injustices in the past 150 years. If you read economic analysis in the financial press, the guiding principle continues to be “winner take all.” And this has been used to rationalize environmental destruction around the world and everything else that flows downstream from that.

This phenomenon has been called “Social Darwinism.” Let's call it “Darwinian Capitalism.”

Under Darwinian capitalism, the reasoning is that if you’re the winner in any contest, aren’t you therefore also, by definition, then the “fittest?” This kind of thinking reveals a great deal about the glaring deficiencies in our socioeconomic model, which are now coming back to haunt us.

In the abstract, capitalism as we know it allows one’s ego to believe that everything one has accomplished is somehow due to one’s own hard work and wits. Our context, privilege, and nurturing environment had nothing to do with it. Similarly, believing that everything is due to having or not having “good genes” is also part of that legacy.

Unfortunately, this is only half true, if even that.

Yes, of course, working hard, striving for a better life, and all the rest are absolutely required to succeed at anything, but even in Darwin's view, the personal traits that allow one to do that are often just dumb luck. And, yes, there are many examples of genetically “gifted” people whose success is irrespective of their nurturing: child prodigies in music, mathematics, linguistics, and science. And no one doubts that LeBron James has natural talent. But that’s not most people. Actually, statistically it’s hardly any people. And, more importantly, that’s not what “civilization” was built on.

The invention of agriculture is often credited as the mother of civilization, not because it fed the king better, but because it fed the masses.

Darwinian Capitalism: an incomplete model

The discovery of epigenetics – that evolutionary changes in organisms are due to the proteins that control genetic “expression,” not just inherited genes, and the incalculable impacts that has on evolution and “survival” -- indicates that Darwin’s understanding was child’s play compared to the complexity of actual biological evolution.

The impacts of nurturing in directing the course of our evolution and how our socioeconomic system operates – who become the haves and who become the have-nots -- is turning out to be at least the equal to the differences in our genetics, and perhaps more so.

The truth is that in many cases today one’s health and success, and even one’s IQ, may correlate more closely with the zip code you grew up in than the “fortitude” of your DNA. Yet, Darwinian capitalism continues to drive much of our misguided tax laws, industrial subsidies[2], and other public policy, even when it leads to diminishing returns like the kind we’re seeing in our the U.S. today (income inequality, opportunity inequality, homelessness, rising suicide rates, falling longevity, etc.).

Over-reliance on Darwinian capitalism enables greed, inequality, and destruction of the planet in a self-reinforcing cycle that works for some in the short-run, but is weakening our cultural dynamism, entrepreneurship, and the value of human capital, while increasing the global tragedies of the commons, in the long-run.

For all its patina about individual freedom, Darwinian capitalism works against democracy and the public good, and incorrectly favors the individual over a functioning social system.

Ironically, everything we recognize as "civilization" – the rule of law, reliable public services, negotiable currency, equal rights, public infrastructure, due process, regulated and trusted markets, and democracy itself – requires favoring the good of the many over the advantage of the few: the triumph of the common good over the private desires of individuals.

Without a system that benefits the many over the few, civilization begins to fail. But the remedy to addressing social inequality and affordability is by focusing on reforming things that are the root cause, not attacking individuals and classes of people. Otherwise, we end up with the kind of draconian, top-down, undemocratic laws now running rampant in California.

Believing, “Let the have-nots make it on their own” is the same as believing, “Let’s attack and blame everyone who owns property or assets (the so-called “rich”) to fix all that ails us.”

Neither of these approaches work.

So, how exactly, do we fix all our inequality problems in a way that does not kill the goose that laid the golden egg: a prosperous and robust middle class?

And then there’s this

Automation has been with us for over 150 years. But today automation, robotics, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of things are fundamentally changing the very definition of work and the role of the individual. This has been great for the fundamentals of wealth building, which we measure in terms of productivity. And, for more than a hundred years this was happening at a pace that the average person somehow kept up with.

No longer.

So, how do we deal with the fact that this growing trend needs fewer people to achieve it?

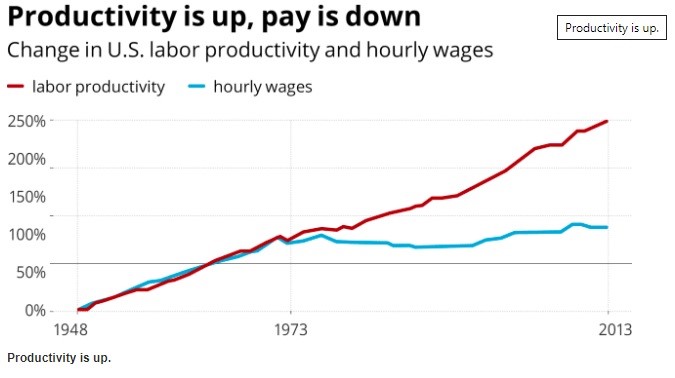

Consider this chart. What it shows is that since 1970, productivity has increased dramatically, while average hourly wages have nominally stayed the same (and are down 11.4% inflation adjusted). And what is not shown is that job creation has also been dropping.

This is nothing short of catastrophic for the average wage earner.

Credit: Tel Aviv University

Dr. Roey Tzezana, a researcher at Tel Aviv University and a research fellow at Brown University, puts it this way,

“The state and the economy are advancing by storm — but the workers are almost not benefitting from this progress and are left behind.”

And

This “doesn’t match the ideas of democracy because democracy is based on the middle class, It is harder for workers from the lower class to vote in an intelligent manner and make intelligent decisions. It is a situation that over time does not enable the continuation of democracy as we know it.”

This inability to “make intelligent decisions” now includes the vast majority of our local, regional, and statewide elected officials, most of whom are in so far over their heads, it’s frightening.

The continuing question of affordability

The statistical “wealth gap” in our world is well known, and does not need to be repeated here. And the intricacies of crafting equitable tax law could fill volumes. But, there’s little question that mega-rich corporations need to pay some taxes -- perhaps an alternative minimum tax for companies with over ten billion in earnings -- because they are benefiting from the government services, roads, schools, and infrastructure that the rest of us are paying for. And the government needs to tax individual billionaires more (income tax rates for the super-rich are at historical lows).

Even Warren Buffet and Bill Gates are pushing for that, to ensure that everyone at least has “boots.”[3]

It makes sense that a lot of people are angry about the inequities in our system. But we ignore fundamental economic principles and how markets work at our peril and risk making things worse in the longer term if we made bad decisions.

In California, these questions relate directly to how we address our social, economic, and environmental challenges, how we plan for growth and housing.

The path Sacramento legislators are taking to create more “fairness” in housing policy is the wrong direction. I’ve continued to argue that all real public wealth is the result of the efficient utilization of private capital (the tax base), which is measured as “productivity.” Taking private funds and putting them in the hands of unaccountable, unelected agencies has never proven to be an efficient use of capital.

Economics is irrespective of how one feels about “capitalism” in general, Darwinian or otherwise, or whether one favors more or less socialistic policies. It just is what it is.

Doubling down on stupid

“If we want things to stay the way they are, things will have to change”

Giuseppi Di Lampedusa ~ The Leopard

In California, politicians and major corporate interests are charging forward in a desperate attempt ‘grow our way’ out of our problems. The uncontested assumption that a “Build, baby, build” mentality and hyper-stimulation of growth and consumption will cause all problems to magically solve themselves is a fool’s errand. And as I noted in my recent article on Faster Bay Area, it is the height of absurdity to believe that the very same Darwinian capitalist forces (major Bay Area tech companies) that benefit the most from public transportation and real estate development should be allowed to craft public tax policy to “solve the problem” -- taxes that will mostly impact the rest of us, the hard-working middle class.

With regard to environmental impacts this is particularly dangerous thinking. [4]

Let’s consider for a moment just the immediate impacts of building and development, because building buildings, and the thousands of the associated industries, products, and activities that includes, is the biggest human enterprise on the planet.

Fundamentally, we are still building and developing using pretty much the same materials and construction methods that we’ve been using for centuries. But, even if everything we ever built,[5] going forward, is LEED certified double platinum, it wouldn’t put a dent in the global supply-chain, ecological damage it is causing.

Consider just the CO2 emissions impacts shown on this chart.

Credit – Architecture 2030

What this chart shows is that the climate impacts of the materials used to build buildings are 9 times more impactful than the operations of that building once it’s completed. And these are just the carbon impacts. It doesn’t even factor in the impacts of global habitat loss, soils destruction, water usage, species extinction, and other social, cultural, and economic impacts caused by resource extraction, processing, shipping, and manufacturing.

Even if we evaluated this purely on financial terms, the “natural capital” cost of building is many times the real estate value of the completed project. This is irrespective of whether we’re building commercial, retail, or industrial space, or whether it’s high-density housing or single family homes.

So, considering that we have not found a way to build anything close to what could be called truly “green,” doubling down on more of the same, as our leadership in Sacramento is demanding, is an incredibly bad idea at this time, particularly since there is no evidence that our societal “affordability” problems (housing, education, health care, etc.) are being caused by lack of growth.

“But it will be expensive and people will lose their jobs!”

When ideas like a “Green New Deal” or a “Blue New Deal” or whatever color deal is proposed, the most immediate reaction by Wall Street owned politicians is, no we can’t even think about that because it would be too expensive and too many people would lose their jobs, or a hundred other excuses for why we can’t or shouldn’t change.

The fallacy in that is that the change is coming anyway. It has to or those same politicians will lose their jobs even faster when the economic consequences of not changing overwhelm us.

Trying to predict the future with certainty is pointless. But the only thing more foolish than that is to not learn from history.

It would be a huge mistake to believe that creating a new economic model, one based on transformation, restoration, preservation, innovation, cradle to cradle product life cycles, and restorative principles, along with massive investment in rebuilding infrastructure and jobs and skills training will be any less vibrant or profitable than the system we have. In fact, it’s hard to imagine that it won’t be far more profitable, while also being more equitable.

I’m not a fan of Andrew Yang’s idea of just giving away money, but there’s no doubt that when regular people have more money in their hands, they tend to spend a greater percentage of it on basics such as food, clothing, housing, education, and healthcare, whereas major corporations and corporate executives tend to spend it on executive compensation, stock buy backs, and nonsense (yachts, private jets, lavish homes, etc.).[6]

Strong economies, like democracies, are built from the bottom up, not the top down.

If we want to have any chance of delivering the richness of the natural world that we presently enjoy to future generations, we cannot keep doing what we’re doing the way we’re doing it. That’s a hard cold fact. Because all Darwinian capitalism will do is find a way to make money off our own demise.

Consider the absurdity of this example. In the past ten years, our great financial minds have created something called “catastrophe bonds,” or “cat bonds” for short. They are basically a derivative bet to make money off of environmental catastrophes. The absurd part, of course, is that the greater the environmental catastrophe, the longer the odds the wealth will still exist to honor the bond's insurance premium.

As expected, demand has been high.

Credit: Bionic Turtle

Changing our fundamental beliefs is as essential as it is daunting, but it’s the core of our present day challenges. Part and parcel of overcoming this inertia to preserve the status quo is human psychology. Unfortunately, we remain predominately driven by visceral and emotional impulses, first and foremost. We tend to only consider longer-term consequences and think things through after directly experiencing catastrophic failures (seeing it happen to others on TV appears to have little effect).

To paraphrase Princess Leia in Star Wars, “We are our only hope.” Knowing all we now know, there’s no question that solutions will take unprecedented collaboration locally, nationally, and internationally. But, I wonder if we’re capable of doing that.

I have serious doubts.

The wealth of the 500 richest people surged 25% in 2019[7] and according to The New York Times, the richest 1 percent in the United States now own more wealth than the bottom 90 percent. Meanwhile, Amazon (a company many of us like and depend on) pays no taxes on approximately $240 billion in earnings, and Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world with an estimated net worth of $120 billion, spends is excess cash dreaming about space travel: as if there aren’t any pressing problems right here on this planet.

Self-interest and short-sightedness have evolved in our species and served our ancestors well in a competitive world on the savannah. But are they hard-wired into our genes? Have eons of evolution in times of scarcity shaped our behavior to such an extent that no matter how much we have we will still feel like we’ll never have enough?

Are we doomed to be driven by forces that act like some kind of childhood neurosis that may have once served a purpose, but is now impeding us from reaching our full potential? Has life has gotten so fast and complex that we can’t hear ourselves think, anymore? Or are we just overloaded by so much conflicting information that we can’t make good decisions?

I don’t know. But I’m worried because as pressures mount we seem to be losing our ability to deal with complex human emotions-- the thing that keeps us connected to each other and ourselves. And that gets reflected in public policy decisions.

Steven Jay Gould, one of our world’s foremost thinkers, had a theory about this that pre-dated Taleb’s “Black Swan” concept.[8] He said that things don’t change gradually, but instead build up and then change very quickly all at once.

He called this phenomena “punctuated equilibrium.”

It is a certainty that the more we stress the planet the greater the odds of an environmental “punctuated equilibrium” in our future.

[1] Bjørn Lomborg, a visiting professor at the Copenhagen Business School, is director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center. His books address how we might prioritize our efforts for maximum outcomes and include “The Skeptical Environmentalist,” “Cool It,” “How to Spend $75 Billion to Make the World a Better Place,” “The Nobel Laureates’ Guide to the Smartest Targets for the World,” and, most recently, “Prioritizing Development.”

[2] Taxpayers in industrialized nations spend a trillion dollars a year subsidizing unsustainable industries like oil exploration and production …at a time when energy are among the richest companies on the planet. And we subsidize agri-business, like growing cotton, one of the most water-intensive crops in world, in the southern deserts of California.

[3] Let’s face it, if you make $10 million or more a year and you can’t afford to pay higher taxes and still make ends meet, you have problems that no amount of money will solve.

[4] See The IPCC Report on Climate Change in the Age of Entitlement, Growth Addiction and Urbanism

[5] Existing buildings presently represent 40% of our energy consumption in their daily operations.

[6] All rationalized as necessities under Darwinian capitalism.

[8] https://marinpost.org/blog/2019/12/12/party-on-to-the-apocalypse

READ PART ONE - The Dow Jones, CalPERS, and Us

READ PART TWO - When the housing “crisis” meets a financial crisis, who will pick up the tab?

READ PART THREE - Party on to the Apocalypse

Bob Silvestri is a Mill Valley resident and the founder and president of Community Venture Partners, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit community organization funded only by individuals in Marin and the San Francisco Bay Area. Please consider DONATING TO CVP to enable us to continue to work on behalf of Marin residents.