Blog Post < Previous | Next >

UN Population Division

Can Europe defend itself?

Yes, it should be able to

In May 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron warned that Europe could no longer rely on the U.S. for its defense, declaring that NATO was experiencing “brain death.” He urged Europe to develop an independent defense capability — a warning that came nearly a year before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, European leaders failed to act on Macron’s prescient call to action, as it would have required a substantial increase in defense spending — at least 1% of GDP. Instead, they continued to depend on the U.S. security umbrella, despite its growing unreliability.

Now, five years later, following the recent Munich Security Conference — where the U.S. signaled that Europe was on its own — European leaders find themselves in a state of panic.

Let’s review how the defense capabilities of the European members of NATO compare with Russia along 3 different dimensions:

- Demographics

- Economics

- Military equipment

Demographics

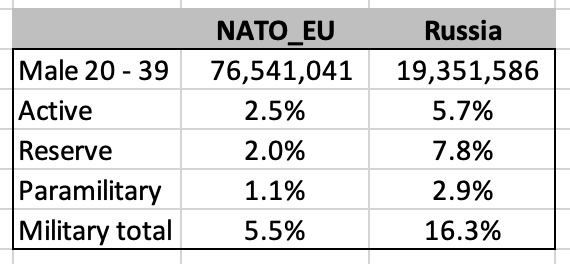

Let’s look at the count of military personnel grouped in 3 categories:

- Active. Currently on active duty serving full time in the military.

- Reserve. Reserve forces are not kept under arms. They are available to mobilize when necessary.

- Paramilitary. Armed units that are not considered part of a nation’s formal military forces.

Based on the most recent figures, the European members of NATO (NATO_EU) have a lot more military personnel than Russia does. The NATO_EU group has 1.9 million active personnel or 75% more than Russia (1.1 million).

The personnel military burden on males 20–39 years old is a lot lower for NATO_EU vs Russia. As shown below, the total military personnel (as specified) represents only 5.5% of the defined male population for NATO_EU vs 16.3% for Russia.

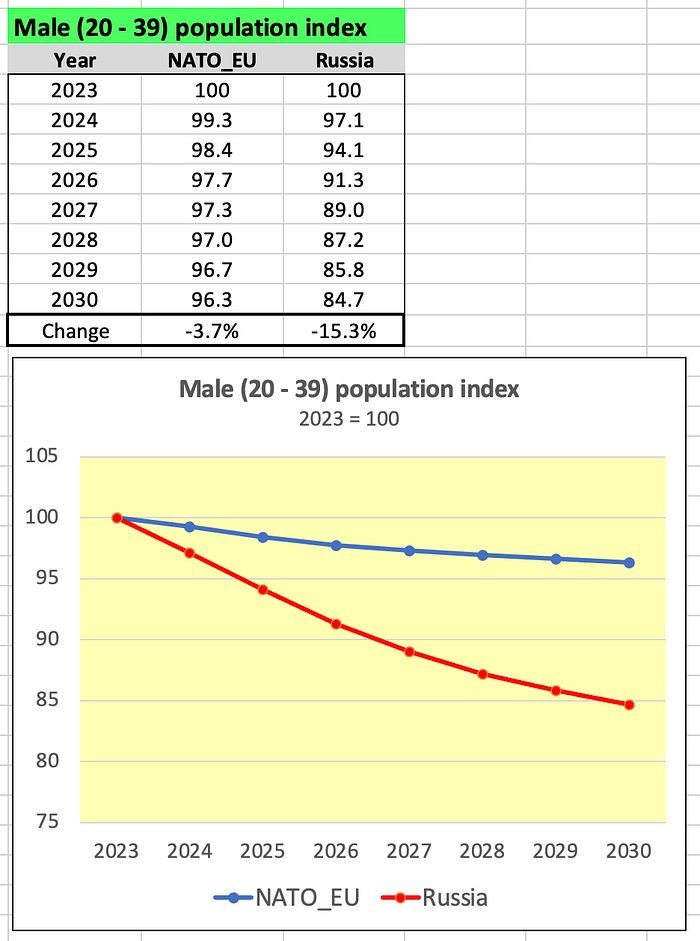

I am unclear whether Russia’s figures reflect the huge casualties incurred in the war with Ukraine. The Economist estimates that between 462,000 and 728,000 Russian soldiers have been killed or wounded to date. Let’s review the UN Population Division data regarding Russian males 20–39 years old.

The table above indicates that the Russian male population (20–39) was experiencing a baseline demographic contraction of close to — 2% or — 400,000 individuals per year by 2020–2021 before the war with Ukraine. These figures did not change much in 2022 and 2023. Therefore, it is not unlikely that the 2023 figures, relative to the present, overstate such a population by close to 400,000 or more (referring to The Economist number of casualties of 462,000 to 728,000).

Even absent the impact of the war with Ukraine, the UN Population Division projections (beyond 2023) suggests that the NATO_EU demographic advantage will accelerate till 2030. Indeed, such projections suggest that by 2030 the Russian male population (20–39) would shrink by — 15.3% vs. only — 3.7% for the NATO_EU group. This entails that the NATO_EU mentioned male population would rise from 4.0 to 4.5 times the Russian one.

As reviewed, the NATO_EU group demographic advantage over Russia is formidable.

Economics

Economy size

Even after adjusting for purchasing power parity (PPP), the economy of the NATO_EU group is about 5 times larger than Russia’s. The graph below discloses the representative time series over the 2014–2024 period. By 2024, NATO_EU’s GDP on a PPP basis was $34.1 trillion vs only $7 trillion for Russia.

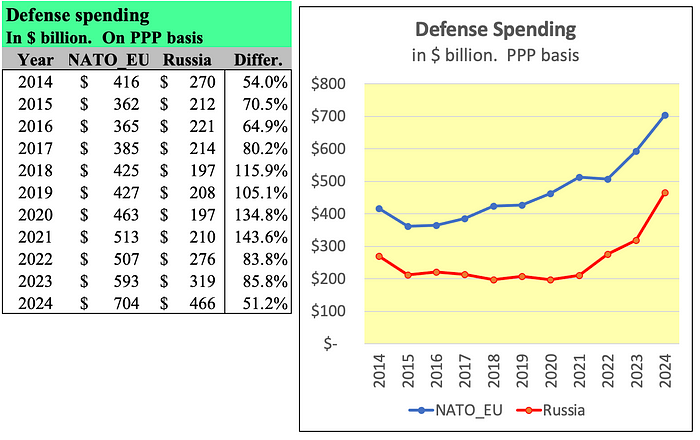

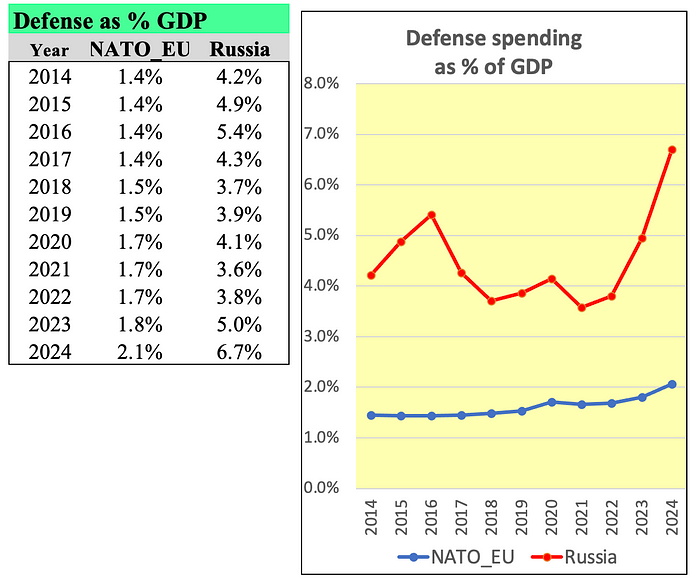

Defense spending

The Media recently stated that Russia was spending more on defense than all the European members of NATO (NATO_EU) combined. The Media arrived at that conclusion by multiplying the Russian defense expenditure by a purchasing power parity (PPP) factor. But, in doing so, they omitted to do the same for the NATO_EU defense expenditure. I did that using the most recent World Bank data and applying the same PPP factor for the entire time series (not a perfect method, but still informative given the limited data available).

On a PPP basis, NATO_EU spends a lot more on defense than Russia does. In 2024, NATO_EU will have spent an estimated $704 billion on a PPP basis, or 51.2% more than Russia’s $466 billion.

Next, when we focus on the defense spending burden on the economy, the NATO_EU group currently spends on defense only 2.1% of GDP vs 6.7% for Russia. Thus, Russia’s defense burden on its economy is more than 3 times higher than for the NATO_EU group.

Russia’s economy is experiencing defense spending related inflation. Inflation is high at 9.5%. To fight inflation, its central bank is keeping short-term policy rate near record high at 21%. Meanwhile, long-term rates are also very high at 16.3%, as investors anticipate that inflation will keep on rising above current level. Russia’s economy is also experiencing defense related capacity constraints as its unemployment rate is at a record low of 2%.

By comparison, the NATO_EU group has an economy with much slack. Inflation is low at 2.4%. Long-term rates are only 2.5%, as investors expect inflation to remain low. Unemployment is relatively high at 6.3% confirming the slack in the economy.

In view of the above, Russia’s economy may be hard pressed to spend more on defense. Meanwhile, the NATO_EU group has plenty of spare capacity to spend more on defense.

A closer look at European NATO members defense spending

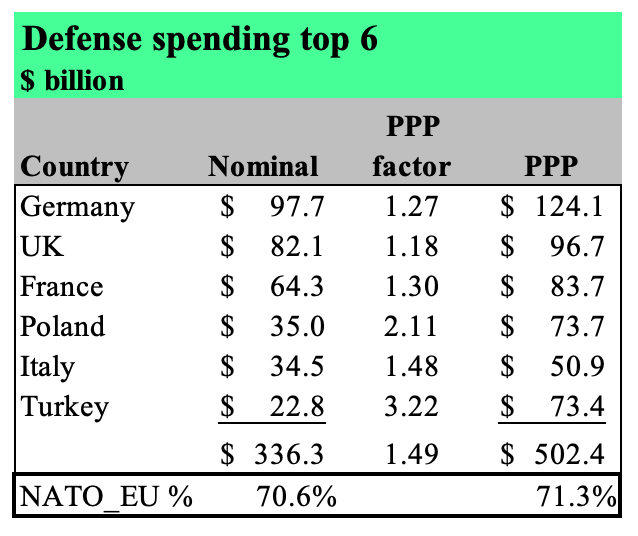

The top 6 European countries account for 70% of the total defense spending by the 29 countries that are part of the NATO_EU group.

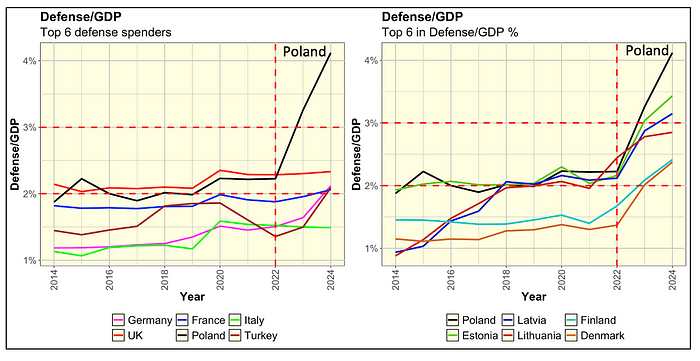

The two graphs below illustrate defense spending as a % of GDP over the 2014 to 2024 period.

- The graph on the left shows the top 6 defense spenders in $. These are the same ones as in the table above.

- The graph on the right shows the top 6 in defense spending as a % of GDP.

Poland belongs to both groups. It represents a leading benchmark in terms of defense spending commitment.

Within the two graphs, I added two horizontal red dashed lines representing defense spending as a percentage of GDP: one at 2% and another at 3%. In 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea, the NATO/EU group agreed that a 2% defense-to-GDP ratio was appropriate. Then, in 2022, after Russia attacked Ukraine, the group decided that increasing this level to 3% was more suitable.

I also added a vertical red dashed line in 2022 marking the onset of the Russia — Ukraine war.

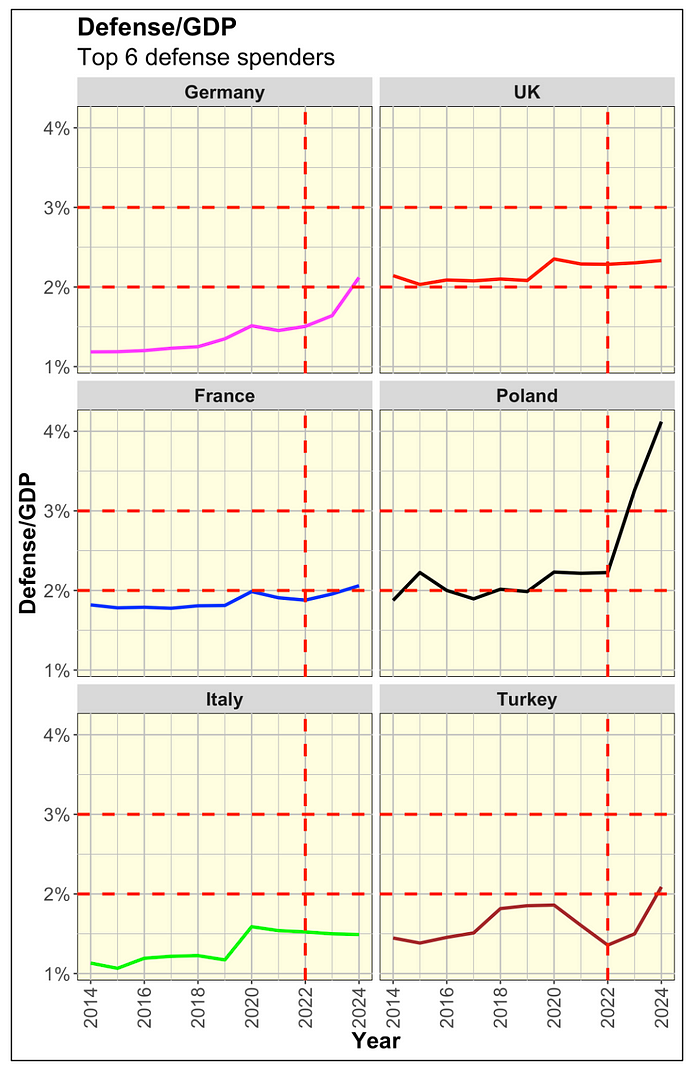

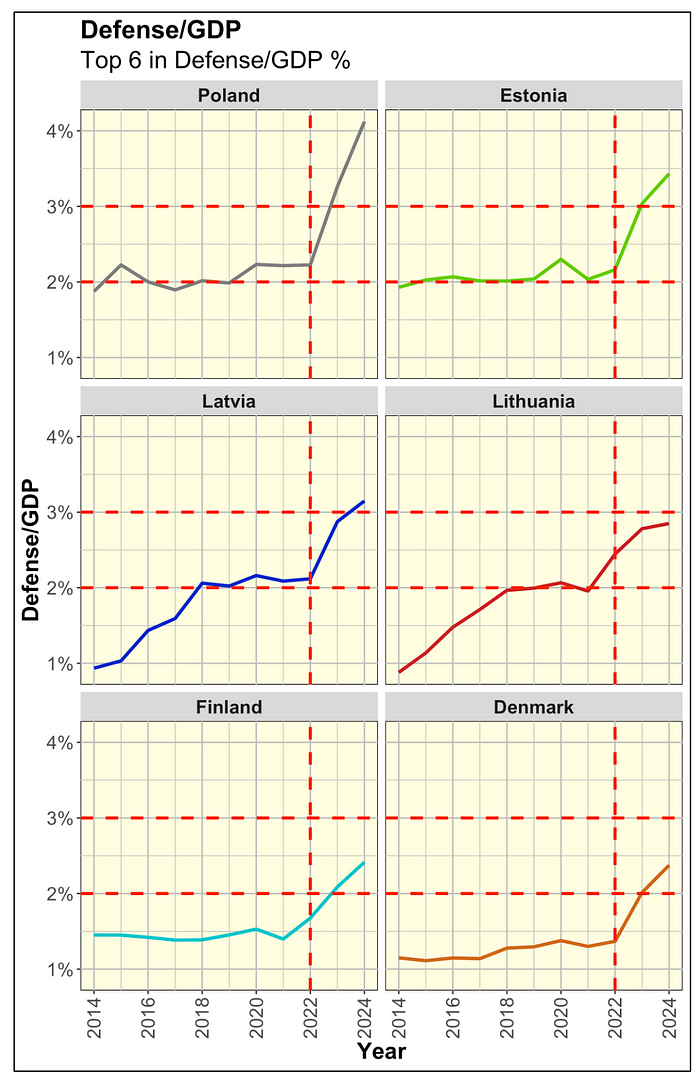

The two graphs above are a bit overcrowded. So, let’s split them up.

First, let’s focus on the top 6 defense spenders. Half of them have been sleeping at the wheel, as they often committed far less than 2% from 2014 to 2022 (Germany, Italy, Turkey).

Even the onset of the Russia — Ukraine war in 2022 was not enough of a wake up call for many of them. See the lack of response in France, Italy, and UK where their respective defense spending commitment remains flat going forward.

Poland, bordering Ukraine, has reacted a lot more than its peers. First, it committed to the 2% level way back near 2014 (much earlier than its counterparts, except for the UK). Second, by 2022 it very rapidly committed to the 3% level (no one else among the top 6 is even close to that level). By 2024, Poland even crossed the 4% level.

When we focus on the top 6 in defense spending as a % of GDP, it is a very different story. Poland, part of both groups, remains the leader at over 4% by 2024. But, notice how this entire group reacted very quickly by boosting their defense spending by the onset of the Russia — Ukraine war in 2022. Beyond 2022, they are all way above the 2% threshold. And, 3 of them have crossed the 3% threshold.

Countries who are close to Russia or Ukraine have responded vigorously by boosting their defense spending since 2022. Meanwhile, the ones who are further away have not responded as much.

Given the US withdrawal of its support for NATO at the recent Munich Security Conference, this is likely to change. And, the laggards (in % of defense spending) may have to catch up to the leaders and quickly head towards the 3% level and above.

Military

There is very limited data on military equipment. The best data I could gather was outdated as it was collected before the Ukraine war. Thus, the figures probably way overstate the military equipment that Russia has left.

Russia has far fewer tanks than it did back in 2020 (13,530 tanks). According to various sources, Russia has now 2,000 tanks operating in Ukraine and another 3,345 in Russia that are not combat-ready. If we could go line by line, we would uncover that the Russian military equipment inventory is much lower than as depicted above. The inventory of the NATO_EU group may have attrited too, but most probably less so than Russia’s.

Regarding military satellites, the count within the table does not factor Starlink with 6,900 satellites. This private company would most probably be glad to lease these satellite services to the NATO_EU group at a reasonable cost.

The nature of warfare has dramatically changed since the above table was compiled. Tanks may have become worthless in the age of drone warfare. If we could factor in technology (drones, Starlink network, automatic weapons system (AWS), etc.) and quality, it is likely that Russia’s military equipment and readiness does not compare well vs the NATO_EU group.

NATO-EU Defense: A Matter of Will, Not Might

NATO and the EU have ample resources to counter Russia, yet they have so far lacked the collective will to do so, as evidenced by several factors.

1. Internal Divisions on Russia

NATO-EU is not uniformly anti-Russian. Hungary and Slovakia openly support Russia, while Austria enables sanctions evasion through its banks, which offer intermediary financial services via shell companies in Liechtenstein. Moreover, as of late 2023, Austria still imported 98% of its natural gas from Russia.

2. Disunity Among Leading European Powers

Germany and France, the two dominant European nations, struggle to form a cohesive anti-Russian stance.

- Germany: Two major political parties lean pro-Russian — the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), polling at 21%, and The Left, at 5%. Despite the risks, Germany may reconsider its reliance on cheap Russian natural gas post-conflict.

- France: Political views on Russia remain fluid and controversial. Far-right leader Marine Le Pen faced scrutiny over a 2014 loan from a Russian bank, repaid early amid a political scandal. The far-left party La France Insoumise has also shifted toward a pro-Russian stance. Additionally, France’s trade and investment ties with Russia are expanding.

These political and economic entanglements explain why both Germany and France have been slow to increase defense spending.

3. The Urgency of Increased Defense Spending

The recent Munich Security Conference underscored the need for Europe’s top six economies to commit at least 3% of GDP to defense. Some, like Noah Smith in his Substack article “It’s Time for Europe to Stand Up,” argue that 5% would be more appropriate given the current geopolitical climate.

For NATO_EU it is also an issue of logistics. Coordinating and implementing military strategy among 29 European members will be challenging. However, keep in mind that Russia’s performance in these areas is lackluster at best.

In view of all of the above, despite the mentioned logistics challenges, Europe should be able to defend itself just fine.

THE END