Blog Post < Previous | Next >

CVP-Edvard Munch

Desperately Seeking Solutions in a Soundbite World

The wisdom of the crowds or the Lord of the Flies?

In the past 100 years, communications technology has changed everything. It started with motion pictures and the invention of “movie stars,” resulting in the ability to make gobs of money from “virtual” reality. Then came the rock stars, who ruled the roost for a while by selling songs to worldwide audiences. They were quickly followed by sports mega-stars broadcast on satellite and cable TV, and exalted Wall Street financiers trading at the speed of light using digital algorithms, leading to today’s internet billionaires, all because technology has now made it possible to monetize the replication of images, video, snippets text or any content to an audience of billions, in real time.

This ability to crowd-source everyone’s opinion 24/7, was lauded as the “wisdom of the crowds,” in the 1990’s. But, with the ubiquity of enabling technology that gives all participants equal digital powers, what has become indecipherable is the difference between whose opinion is qualified and whose really isn’t.

In our new world of digital false equivalencies, everyone is an “expert,” regardless of their qualifications, intelligence or morality. This ability to appear to be more than one really is, bolstered by gaming our perception of “reality” with likes and retweets, has gotten to the point that it is driving critical thinking and values down to the lowest common denominator. What we end up with are snippets of “attitude” that render meaningful conversation and problem solving impossible.

Worst of all, in a world where there is no way to truly assess if there is any “there” there, perceptions of “public opinion” can dramatically influence the decisions of policymakers, in spite of the fact that it may be driven by small groups spewing out glib catchphrases to carefully manipulate media.

In this environment, being clever is better than being intelligent. Being good at aggressive branding and marketing is better than being educated and thoughtful. And, having life experience and wisdom is devalued by the noise to the point of being relegated to oblivion.

This phenomenon is seriously eroding our political process and disproportionately swaying the thinking of elected politicians, who unfortunately have a strong tendency to “go along to get along.”

On a planet faced with an increasing number of serious environmental, economic and social justice related problems, this puts our democratic system in danger of cascading down into a totally dysfunctional mess, incapable of addressing any problems.

The art of the troll

In media, politics and social discourse, more and more it’s all about anticipating the responses of one’s opponent and playing "gotcha" by finding the fatal flaw in their statements then regurgitating soundbite talking points. Forget about Russian bots hacking our elections, it’s hard enough to just deal with the comments section in the Marin IJ.

There are anonymous internet trolls (why are they always anonymous?) who comment on every article I write, on any topic. But, you can tell from their comments that they were compelled to hit the keys after reading only a few sentences or being set off by certain words that sent their texting thumbs fidgeting to produce torrents of buzzword-filled verbiage that usually misses the entire point of the article.

I’ve even had my writing lambasted for being “merely opinion,” even though the piece was titled an "opinion piece."

A mirage of public support

Most people go about their lives, minding their own business. For anyone raising a family, taking care of an elderly parent or just trying to make ends meet, doing those things is overwhelming enough to have time for local politics. Most people feel, for good reason, that the less they interact with their “government” the better.

This vacuum of real participation (vs. virtual) empowers media and technologically savvy special interest groups.

Today, “public support” can consist of the prolific opinions of a few individuals with millions of anonymous “friends,” who can manufacture the appearance of widespread participation. However, on closer inspection, many of today’s “movements” and “stakeholder groups” are nothing more than a digital mirage and an attractive web site page.

But, that has not and will not stop them from wielding enormous political power.

If you consider that money equates with political “voice,” and that voice is mostly enabled by technology and media, you begin to understand how bizarre legislation can seem to suddenly come out of nowhere and quickly move toward approval in Sacramento, before the general public even knows what’s going on.

Trumpeted as being all about solving the “housing crisis,” Senate Bill 827 may be the best example yet of legislation by soundbite.

The rise and inevitable fall of SB 827

In March and April of this year, the elected representatives of California’s two major cities, Los Angeles and San Francisco, voted to outright oppose Senator Scott Wiener’s Senate Bill 827. Most other cities and counties around the state did some version of the same thing.

The details of the proposed legislation have been well covered in the press and in this publication. However, the essence of it is that the state would take away the sovereign right of locally elected government to control its own planning, growth and zoning, and determine what kind of development that would be allowed “by right.”

The rejection of this proposed legislation is a very big deal and it leaves Scott Wiener on thin ice, politically, having been rejected so decisively in his own home town.

These cities didn’t say they’d consider the legislation with amendments. They flat out rejected the entire concept and one of the major reasons was due to the massive grassroots, community uprising that ensued after it was proposed. This unequivocal opposition cut across the full spectrum of income groups, ethnicities and races. The opposition included small rural towns and big urban cities: middle class suburban communities and disadvantaged inner city neighborhoods. It included Democrats and Republicans.

But, how could this be? The press has been falling over backwards to claim that there is massive public support for SB 827, which now looks like it may end up being Senator Wiener’s Waterloo.

So, how does a nonsensical proposal like SB 827 come about in the first place, when it turns out that so many people oppose it?

The publicity surrounding SB 827 was primarily driven by the YIMBY movement that we are told is sweeping the nation. We were bombarded almost daily in the drama-loving press with reports of their successes, political support and how many tech czars were throwing their weight behind them.

While it is true that Senator Wiener – like most politicians who are primarily interested in feathering their own nests -- has been receiving out-sized financial support from construction unions and real estate development interests, and tech executives desperate to find housing for their new hires, on closer examination it looks like the “massive” YIMBY support is an example of the type of marketing mirage I’m talking about.

The YIMBY “movement” appears to be a relatively small group of clever, urban, tech and marketing savvy individuals, who have fooled the media into thinking they speak for a majority, when in fact they only speak for themselves.

The YIMBY party platform is that entitled, highly educated Millennials should be able to live anywhere they want, including the most desirable neighborhoods. Therefore, government should throw out hundreds of years of property rights laws and legal provisions that declare a city’s General Plan its sovereign constitution, and remove all zoning restrictions, so the “market” can build enough housing to make prices more attractive. The argument is that we should do this because over development will lower housing costs and because it is “fair,” and we are required to do our “fair share.”

In our “Wag the Dog” world, words like “fair” get our attention, until we sit down and think about it for ten minutes. Aside from the fact that the YIMBY housing ideas are based on nothing but wishful thinking, confuse real estate boom and bust cycles with market pricing trajectories, and would probably bankrupt most California cities, statistics show that it has little relationship to the real world.

By and large, most Millennials are doing what every generation in history everywhere in the world has ever done: getting married, working hard, buying cars, saving money and buying a starter home they can afford or moving to places that offer more opportunity and a better quality of life for their families. They are deciding that cool coffee bars and night life don’t really matter that much.

Welcome to the real world

As much as the YIMBY ideology may appear logical in the fast moving world of tech innovation and investing, if you apply it to real world challenges, like housing and planning, things that impact and involve real people from all walks of life (who could care less about Silicon Valley, Hollywood or Wall Street), it results in real damage and hardships and dislocations and destruction of people’s lives and the shredding of the social fabric of cherished communities.

Much like Wall Street traders, VCs and tech CEOs demand clear, simple concepts and quick, guaranteed exit strategies, because God knows they have to hurry up and get on to saving the world with yet another way for you to send pictures of your cat.

They remind me of Hollywood, where the saying is that if you can’t pitch a movie idea while riding two floors in an elevator with an executive, the movie isn’t worth making. I guess that explains the “wonderful” state of Hollywood movies today – such depth, such important subjects being addressed.

None of this is to suggest that we are not living in a time of a crisis of “affordability.”

Note that I do not separate out any particular kind of affordability, such as housing, from other types like healthcare, college tuition and regressive taxation, because to do so would obfuscate the real issues.

Still, housing affordability is where this whole conversation about a “crisis” and the genesis of proposed laws like SB 827 began, more than twenty years ago.

Affordability in the age of creative destruction

There is always an easy solution to every human problem - neat, plausible, and wrong.

~ H.L. Mencken

There is an almost hysterical outcry for immediate solutions to our “housing crisis.” But, unless solutions are presented in dumbed-down catchphrases, most people’s eyes seem to glaze over. If “fixing” the problem takes educating one’s self or actually getting personally involved, few want to hear about it, much less read about it. Our mouse-clicking world has reduced our collective tolerance for bad news to milliseconds.

Unfortunately, if you want a world run by soundbites, you will either get a Donald Trump or a Scott Wiener running your lives. They are opposite sides of the same coin of cleverness and catch phrases and spin.

It has always been axiomatic that you can’t find the right solutions if you’re asking the wrong questions. But, what if that is exactly what everyone keeps doing.

Sacramento is currently in a “top down” frenzy, writing a new law every day to penalize cities and their residents and increase taxes and fees on our state’s residents and businesses to raise money for hyper-development plans that grow grander and grander with each iteration. Most legislators are in a total, political career-saving panic to “solve” our housing affordability problem.

But, what if everything they’re doing, like SB 827, is for naught or will only make things worse.

I’ve been writing about housing affordability solutions for more than 20 years: financing solutions, zoning solutions, planning solutions and practical development related solutions. However, even my writings have generally been in the context of solutions at the local, regional and state level. But, what if the real drivers of “un-affordability” have little to do with what we do locally, regionally or at the state level.

What if housing affordability is just another symptom of the overall un-affordability of living in our society, in general: the un-affordability of housing, healthcare, education, healthful nutrition, legal advice, or whatever? If that’s the case, then we will never solve any of these challenges in a fundamental way, unless we face the facts.

An historical disruption of the labor market

The chart below shows the critical relationship between productivity and wages, since 1980. This chart explains an important reason why affordability has become such a widespread problem.

Since the mid-1970s and exploding in the early 1980s, an irreversible divergence began in the historic relationship between productivity and the efforts of work and compensation and benefits. Nothing like this has happened since the industrial revolution, but the global extent of the impacts today are far greater and more rapid that at any time in history. Suffice it to say, we are witnessing one of the most profound redefinitions of the meaning of “work” in two hundred years.

Since the mid-1970s and exploding in the early 1980s, an irreversible divergence began in the historic relationship between productivity and the efforts of work and compensation and benefits. Nothing like this has happened since the industrial revolution, but the global extent of the impacts today are far greater and more rapid that at any time in history. Suffice it to say, we are witnessing one of the most profound redefinitions of the meaning of “work” in two hundred years.

The resultant dislocations of people and re-allocations of capital that are resulting from this may be impossible to predict but bear examination.

The correlation between wages and education / skills

As the next charts shows, the need for workers who do repetitive jobs, manual or mental, which just 40 years ago represented the majority of jobs available, is rapidly disappearing. This particularly impacts entry level positions, manufacturing, and unskilled workers. So, a lot of people are being left behind. Advancements in robotics and computerization have equally decimated jobs growth in the manufacturing sector.

As technologically-enabled work becomes more productive, fewer people are needed, putting a downward pressure on average wages, but the people who are needed must have higher levels of skill and education. The only jobs left for those without the requisite education or skills are menial service sector jobs, which are generally much lower paying.

This hypothesis is borne out by the data, which again shows a significant rise in lower paying service worker jobs, since 1980.

Unemployment may be going down but wages are not keeping up with the rising costs of living.

Real wages

As the chart below shows, the real (inflation adjusted) wages of people with highly productive skills are rising at faster rate than those without the required education and skills. Wages for low paying jobs have actually been losing ground for the past 28 years.

However, as we will see, even for workers with the most advanced skills, real wages since 1980 are not keeping up with the rising costs of housing, healthcare and education.

This overall affordability crisis is also evident when we look at the inflation adjusted minimum wage, since 1980.

Once again, beginning in the mid-1970s, we see a dramatic divergence in what the minimum wage is in real dollars today ($7.25/hr.) and what it would have to be in order to have kept up with the inflation ($18.42/hr.) as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

The overall impacts of inflation

Having established that wages are lagging real costs and the distribution of wealth is increasingly uneven, let’s consider the impacts of inflation on the affordability challenges for the average person.

Let’s look at the three most serious affordability challenges we face: Housing prices, healthcare costs and the cost of a college education.

Housing Prices: 1980-2018

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average price of a home in the U.S. was 215.28% higher in 2018 versus 1980. However, this national average by no means gives us an accurate picture of housing costs in desirable areas and jobs centers.

The divergence in housing prices between the national averages and in a select number of desirable cities is the “housing” corollary to the “haves” and “have-nots” divergences in wages, noted above.

For example, the home I bought for $80,000 in 1981, in the Washington Park neighborhood of Denver, Colorado (with minimal updating), now sells for over $850,000: an increase of more than 1,000% (ten times the value). Similarly, a 950 square foot home built in 1946, situated in Sycamore Park in Mill Valley, cost about $115,000 in 1980 and would sell for about $1,250,000 today (with a remodeled kitchen and bath): an increase of over 1,000%.

Property values in prime East and West Coast cities are up approximately 800% on average, since 1980. And, just to show that the housing affordability problem is not just an American problem, just look at the comparative price of houses in other hot global markets.

Housing affordability is a global problem.

Healthcare and Medical Care 1980-2018:

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (chart below), prices for medical care rose 643.69% since 1980. In other words, healthcare costing $1,000 in 1980 would cost $6,436.94 in 2018.

Surprisingly, according to the BLS, compared to the overall inflation rate during this same period, inflation for medical care was average. That means pretty much everything else (food, transportation, clothing, etc.) has gone up almost 650% since 1980.

Why millennials are so angry

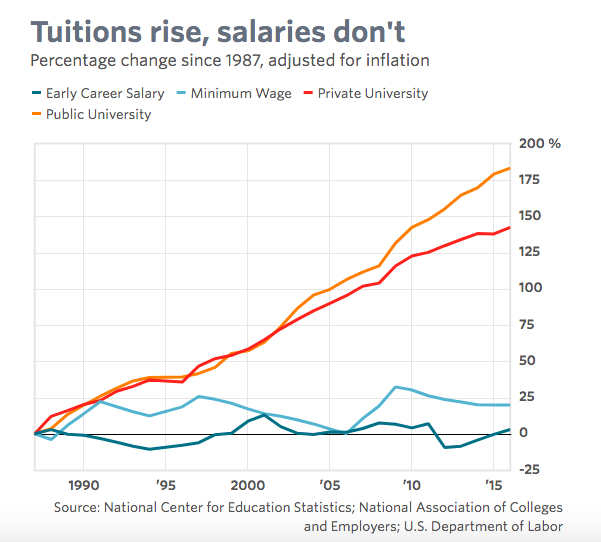

College education Tuition: 1980-2018

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for college tuition and fees were 1,076.22% higher in 2018 than they were in 1980. In other words, college tuition costing $20,000 in the year 1980 would cost $235,243.10 in 2018 for an equivalent Bachelor’s Degree.

Meanwhile, earnings for graduates holding degrees from top schools have only gone up about 250% during the same time period (1980 to 2018) – only 25% of the increase in the costs of a college education.

Something’s gotta give.

The differential between the cost of a college education and the earnings of an average family has mostly been made up for by debt, not by increased earnings (see chart below).

Worse still, wages for people holding a Bachelor’s Degree have not been increasing at all in real terms (see chart below).

At some point, people might be asking if the cost of a college education is really worth the price. But, the truth is that the only thing that keeps us all paying the piper is that the consequences of not having a good college education is even worse.

Putting housing affordability in perspective

What all this data makes clear is that housing “un- affordability” is being primarily driven by factors far beyond the control of local, regional or even state governments.

Ask yourself, how is the average family supposed to deal with astronomical healthcare and college tuition costs and still be able to afford a home on an average person’s salary? How is a young college graduate supposed to deal with having hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt and substandard wages and employers who are paying less and less of their healthcare costs, and still be able to purchase their first home?

The answer is they can’t. It’s just impossible. Only a small percentage of the population can afford to fill the gaps with savings or earnings.

The reasons for the unprecedented disconnect between what we expect to be able to do and what we can actually afford to do are the result of more things than we can list. It is the result of things we could control, like government spending priorities and policies, and things we can’t control like the times we find ourselves in as we transition to a highly educated and fully technologically enabled world.

But, things being as they are right now, we can appreciate why younger generations are fed up and demanding change.

The great danger is that people grasp on to overly simplistic and downright ignorant ideas, such as SB 827, that are based on nothing more than that anger and the ideologies it produces, instead of working together to really address the fundamental changes that need to be made.

The plain truth is that no amount of growth and building will accomplish our shared goals.

People are “infrastructure,” too

People feel more angry, insecure and afraid than at any time in recent memory. Sometimes, it feels like the world has collectively lost its mind and all common sense has been thrown out the window. This is fertile ground for disastrously bad personal and public policy decisions.

What is even sadder about our present situation is its impact on the American Dream. Homeowners, who until recently were seen as the backbone of our country, the ones who by hard work and thrift built and invested in and stabilized communities, are now being portrayed as racist, selfish and enemies of all things "good" for what ails us.

This is a remarkably self-destructive endgame for our economic and political system.

So, what to do?

The data I’ve presented unequivocally argues for massive jobs training and re-education programs of our adult population, with particular focus on increasing skills that are enhanced by technology rather than those eliminated by technology. We must increase the overall earnings power and wealth creation for the average person to be commensurate with the dramatic increases in productivity.

Increasing the number of people who are participating in the 21st century’s super-productive economy is the only way to bring about affordability. This is doubly important when you add in the intense competition we're currently seeing from global labor markets.

However, instead of facing what we really need to do, we are generally ignoring those fundamental problems and falling back on past policies that are doomed to fail. We are increasing tax burdens (decreasing affordability) and pouring billions of dollars into trying to inefficiently build housing in order to “warehouse” those being left behind. We are using up finite financial resources to pay for symptom relief, while leaving the disease untouched.

We still think believe in limitless resources and endless horizons are ahead and that we can “grow” our way out of our problems with preposterous legislation such as SB 827 and SB 828, but we can’t. We keep thinking that some version of the 1930s New Deal work programs and public works projects will fix everything, but they won’t.

The economic disruption we’re experiencing in the U.S. is not caused by the same dynamics that brought on the Great Depression or the major recessions of the second half of the 20th century or even the crash of 2008. The underlying issues today are more profound, more systemic.

This time around we have to primarily invest in people, not things.

The same old, same old

The business of America has always been business, profits and growth, more and more without caring what the long-term consequences might be. That's been our system since our founding. And, that was a good start, but it's not enough, anymore.

In that environment, human values have always been vulnerable, but somehow we kept it cobbled together until recently. For most, the financial collapse of 2008 was the signal that the game had changed, though the previous charts show that the cracks have been forming since the 1980s.

This event and Washington’s gross mishandling of the outcomes – enabling corrupt financial institutions while throwing working people under the bus – has been followed by state governments desperate to remain solvent, to grow their revenue base and create jobs. This has only served to “feed the beast” that created the crisis in the first place, and further shifts the bulk of the financial consequences on wage earners and savers.

If a system always favors capital over people, the only solutions considered will be those that increase profits, which by its very nature will always choose short-term returns over long-term investments. No solutions that involve long-term planning will be equally considered.

Today’s soundbite-driven body politic is synonymous with this quick fix mentality. Ironically, the YIMBY solution is much like the tax cuts for the rich / trickle-down theory, because both are founded on the belief that markets can cure everything. They won’t.

In fact, the irony is that if we continue to rely only on competition and markets to save us, it actually will increase the need to expand the “welfare state,” because without education, healthcare and empowerment more and more people will be left behind.

Our problems are not simply economic ones. GDP is not a reliable gauge of society’s health, wealth or longevity.

If raising the GDP was the only thing we had to do to ensure our collective future, we could just hire every unemployed person and set them to cutting down the Amazon rainforest and strip-mining the life out of our oceans. We’d all make lots of money for a while until we all gasped our last breath of oxygen and died.

Some will argue that our record low unemployment rate disproves my allegations. But, they forget that when the Soviet Union’s economic system collapsed, they technically had an unemployment rate of zero: everyone had jobs but the majority of its citizens were doing “make work” and desperately poor.

Our system is capable of creating its own version of that.

If we only spend money on building infrastructure without investing in people, their education, skills and health, all we will accomplish is creating short-term workarounds. The underlying affordability challenges will remain.

Unless we recognize this, we will never be able to make the long-term investments in people, needed to fundamentally address our social, educational, healthcare and housing affordability challenges.

What a colossal waste

Anger and resentment about our affordability crisis has reached a boiling point. Feelings of unfairness that can drive people to demand socially-destructive legislation (like SB 827) and cast aside democratic principles, just to get what they want, right now.

History has shown that when a political system fails, people start to attack each other, like an autoimmune disease, rather than the things that caused its demise. The pain, injustice and the resultant loss of faith fuels paranoia, suspicions and gullibility, and ultimately turns neighbor against neighbor.

The only difference this time is this progression is cyber-enabled and more prone to manipulation and abuse. All of this has historically led to rash decisions and yearning for anyone who can just “get the trains to run on time.”[1]

This is why ignorant politicians are starting to turn on technology companies and mislabeling their pubescent missteps as evil and monopolistic. But, they are not the problem. In fact, they pay some of the highest wages and offer some of the best benefits in the world. Henry Ford would be proud.

They are not monopolies in the classical sense, achieving what they have by predatory pricing. Companies such as Amazon have achieved their dominance by simply providing consumers with a faster, cheaper, better version of a global marketplace or digital department store. In the past decade, new technology platforms like EBay and Amazon have probably enabled the creation of more small entrepreneurial businesses than all traditional large corporations combined.

Better technology makes predatory, anti-competitive practices unnecessary. And, if you think Facebook or Twitter is invading your privacy, then just turn it off and don’t use it. I guarantee you, your life will not end.

I’m not saying that technology companies are perfect or are not capable of criminal behavior or abuse of their power, or that its CEOs are not just as greedy as any other tycoons who got rich quick, throughout history. They are.

But, if the issue is about our overall affordability crisis, we’re placing blame where it doesn’t belong.

The plain facts are that unless we bring the many who suffer the consequences of our current technological-driven disruption along with the few who benefit from those consequences, the many will eventually drag everything down to the lowest, most simplistic, common denominator that will turn back the clock to darker times and threaten of our democratic institutions.

If we really want to address affordability issues, we’re all going to have to roll up our sleeves and get down to the hard work of figuring out how to do that.

Clever soundbites will get us there.

[1] Attributed to why the fascist Benito Mussolini was elected to power in Italy in the mid-20th Century.