Blog Post < Previous | Next >

C. LeGras

The Fundamental Falsehood Guiding Modern Liberal Politics

It’s the same one that’s been leading them astray for a century – only these days, it’s worse

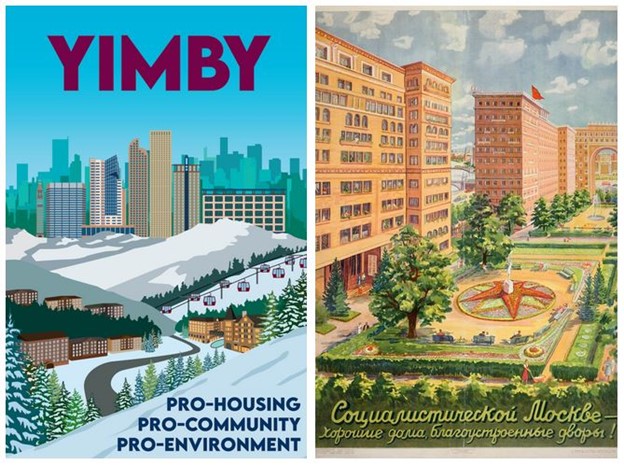

One of the more curious, not to mention consequential, aspects of modern liberalism is its reliance on assumptions that collapse under even rudimentary scrutiny. For example, the liberal “YIMBY” movement (for “yes in my back yard”) assumes that the sole cause of the housing affordability crisis plaguing liberal states like California is a lack of supply. There isn’t enough housing, ergo, housing is expensive. Build more of it, of any type, and prices will fall. It isn’t simple, it’s simplistic.

A robust and growing body of research demonstrates that housing costs are far more complex, involving variables like income levels in different neighborhoods, costs of land, materials, and labor, and market preferences. More fundamentally, the YIMBY theory reduces supply and demand to a meaningless tautology.

Nevertheless, lawmakers in states including California, Washington, and New York have jumped on the YIMBY bandwagon. Over the last seven years, California alone has passed some 400 new laws intended to unleash a new flood of housing supply by limiting or eliminating local zoning, land use, and development rules as well as state environmental reviews. Other bills provide myriad perks to developers of market rate and luxury multifamily housing by eliminating things like setbacks, height limits, floor area ratios, and off street parking.

Supply, supply, supply.

This is all coming from Democrats, particularly liberal Democrats, who until recently were champions of things like housing affordability and accessibility, and, in particular, environmental protections. In contrast these days, California Democrats have embraced trickle-down economics to a degree that would leave Ronald Reagan himself aghast at their audacity.

It’s not just housing. They’re using supply side policies to spur everything from mass transit to wind and solar energy. Everywhere you look it’s “build, baby, build.”

There’s just one little problem: None of it is working.

The YIMBY theory of housing is producing housing that most people don’t want. According to the US Census Bureau, about 82% of Californians live in single family or small multi-family homes (duplexes, fourplexes, townhouses, small apartment buildings). The vast majority of those homes are in low density urban neighborhoods, suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas. This, of course, stands to reason. Most people want space of their own, private or shared front and back yards, gardens, lawns, and trees.

These features aren’t “nice to haves,” enjoyed by the privileged few. They’re fundamental to quality of life.

This isn’t what a majority of people want, but it’s what California liberals are building by the thousands.

Yet YIMBYism is predicated on dense new urban neighborhoods consisting of apartments with no green space. In a very real sense, the movement seeks to turn back time. After a century in which Californians, and Americans in general, flooded out of cities for suburbs, YIMBYs want to claw them back. Which is where the movement rests on another easily disprovable assumption, that, with apologies to Dr. Seuss, a home is a home no matter the type. In other words, YIMBYism is premised on the assumption that housing is fungible.

This is economically illiterate.

A fungible product is one that is identical, or nearly so, no matter the supplier. Commodities are generally close to perfectly fungible. So is currency. The $20 bill in your wallet is identical to the one in my pocket. On the retail side, gasoline is close to fungible. Think of the intersection in your city where there are gas stations on two, three, or all four corners, all offering the same price per gallon. Generally speaking, you don’t care whether you fill up at Shell, Chevron, or 76. You’re going to fill up at the station with the shortest line, or the one that happens to be on the side of the street you’re on.

In reality there is no such thing as a purely fungible commodity. There are tiny variables even with gold bullion — form (bars vs. coins), sale method, storage method, and assay marks — that can slightly affect its value. The $20 bill in your wallet might be torn to the point that you have to go to the bank and swap it for a new one.

The farther you move up the economic ladder from basic commodities, the less fungible the products in question become. Housing is near the top of that economic ladder. No two homes are exactly alike, because every home is located in a different place. Differences may be minimal — think of tract homes in a planned development, or apartments with identical floor plans. Still, each one will have a few slightly different characteristics, like different views, different exposure, different noise levels, different levels, different orientations, different distances from the elevator, etc.

Likewise, different units have different neighbors. It’s much different living next door to a 25-year-old heavy metal fan compared to a retired 75 year old widower. There are also intangibles: Even if you’re looking at identically laid out units in the same building, or different houses in a tract, each one just feels a little different.

Moreover, there’s no such thing as “the housing market.” There are many different housing markets. That’s not semantics: The 22-year-old single recent college grad renting her first grownup apartment is in an entirely different market from the 30-something married couple with a new baby who are looking for their starter home. The heir to a $100 million fortune looking for a Bel Air estate is not competing with the small business owner shopping for a townhouse in Pacoima. And so forth. Yet YIMBYism blots out these myriad differences, on the demonstrably, obviously false assumption that “housing is housing.”

Suffice it to say, not the same.

The same goes with transportation. Liberals have all but declared a holy war on the personal automobile, that foundation of modern economic mobility. Again, we see the assumption: Transportation is transportation, no matter the form. They argue that a light rail or bus line, even a bicycle or your own two feet, are all just as good for getting around as a car. This is, of course, insane. A car is superior in nearly every conceivable way. The only variable in which transit, bicycling, or walking come out on top is emissions, and cars are getting cleaner all the time.

No matter. California liberals have been expanding mass transit at a dizzying pace. More trains, more buses, more jitneys. LAX is about to open a “people mover,” boldly deploying 1960s transportation technology in 2026. They assume that if they spend $3.34 billion on a 2.25 mile rail loop (which works out to nearly $1.5 billion per mile), tens of thousands of people will opt not to drive, ride share, or taxi to the airport, which if you’re smart enough to book a flight outside commute times takes around half an hour from pretty much anywhere in L.A.

Instead, millions of passengers will spend three times as long lugging their carry-on down the street to the nearest bus stop, make a couple-three transfers, then slog another mile to the airport itself.

That’s not hyperbole: I’m writing this post in Santa Monica at 8:30am on a Wednesday. According to Google Maps, if I left for the airport in a car right now, I’d be walking into the terminal in 24 minutes (assuming I’m not parking my own car at the airport, which only madmen do these days).

In contrast, to use transit I would have to 1) walk 0.4 of a mile to the nearest bus stop, 2) wait however long for the bus, 3) ride that bus for four stops, which would take about six minutes, 4) get off that bus, 5) wait however long for the second bus, 6) ride that bus for 29 (!!!) stops, which would take about 45 minutes, 7) get off that bus, and 8) walk 0.9 of a mile to the airport. If I timed every stop and transfer perfectly, I’d be walking into the terminal in 1 hour and 23 minutes. Also, it’s raining right now.

The people mover, when it opens after years of delay, will shave the walk to the airport. So let’s call it an hour – again, assuming perfect timing. What possible incentive do I or anyone have to go through that enormous hassle, aside from saving a few bucks (thanks to L.A.’s absurd airport fees and rides hare policies, a round trip to LAX from much of the city isn’t cheap; about $80 before tips)? You don’t even have to use ride share; as the old saying goes, true love is driving a family member or friend to LAX. Better still, that family member or friend or ride share driver is considerably less likely to stab you than a lunatic vagrant on the bus.

Also not the same

California’s political class spends billions to build it, and no one comes. Despite splurging some $50 billion on transit expansion over the last 25 years, ridership was hitting all-time lows even before the pandemic sent transit systems into death spirals around the state, from BART in the Bay Area to L.A.’s Metro system. Because not all transportation, as it turns out, is created equal.

This post occurred to me as I was reading stories about the immigration raids and resultant protests and riots downtown over the last five days. Not the raids and riots per se, but the policies that preceded them. Yet again, we see the underlying liberal assumption: immigration is immigration, no matter what form it takes.

The seasonal migrant worker who crosses the border at harvest time then returns home is no different from the worker who comes here illegally to work for a few years, send as much money home as possible, then return. The two of them are no different from the family who come here illegally with plans to stay forever and seek residency then citizenship. And they’re all indistinguishable from the cartel or gang member who comes here with criminal intent. We’re just supposed to accept “immigration,” as if millions of people from a hundred different countries comprise a monolithic whole.

For every action, a reaction. Americans got fed up. They got sick of being called racists for the sin of wanting a modicum of order and control at the southern border. You know, like pretty much every other civilized country in the world. They started to resent the howls of bigotry in response to concerns about the bad actors among those masses crossing the open border. Even doddering Joe Bide was talking tough about immigration when he ran for reelection.

Also not the same.

Which is where we arrive, at last, at the fundamental fallacy in modern American — and for that matter, global — liberalism. It isn’t a liberalism that most of us recognize. Liberalism used to stand for acceptance and tolerance, a fair shake for working and poor people, environmental stewardship, and open-mindedness.

Unfortunately, for the last century a mutation lurked in that otherwise healthy political DNA: Marxism.

Until the last 15 or so years it was latent, manifesting primarily in a smattering of university and college classrooms, certain union halls, and a fringe of the arts. It was a slow-growing cancer that implacably took over more political cells, that is, more classrooms, more union halls, more creative output. To paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, it took over gradually, then suddenly. Suddenly, we went from reckoning with the less savory aspects of our national history to a radical movement to effectively erase it as irredeemable and replace it with a collectivist utopia.

The essential core of Marxism is, of course, class. Workers are workers, owners are owners, financiers are financiers, etc. Marx’s overarching assumption was that people of the same class automatically shared the same interests. As members of the proletariat, the farmer, the bricklayer, the factory worker, the blacksmith, the bus driver, etc. were socially and politically indistinguishable. The mason working on office buildings in Moscow was no different from the one building grain silos in Siberia. And so forth. A proletarian is a proletarian, be he an Italian plumber or a Chinese rice farmer. To return to the previous premise, under Marxism human beings become fungible.

Modern liberalism has expanded this fatally flawed premise to nearly all aspects of human existence. Housing is housing. Transportation is transportation. Immigrants are immigrants. All can be categorized, classified, and, ultimately, controlled.

Except, of course, they cannot. That’s because outside literal scientific classification of species, life doesn’t operate according to tidy categories and rules (even in biological classification there are confounders; as Robin Williams once joked, God created the platypus to screw with Charles Darwin). The harder modern liberalism tries to organize the entropy of human existence, the farther it strays from the essence of what it means to be human. That’s why we are seeing a form of authoritarianism on the left that is as worrying as the Trumpian authoritarianism of the modern right.

If liberals in California get their way, we will ride those buses, like it or not, we will live in those indistinguishable, soulless shoe boxes in dense urban cores. We will restrict ourselves to “15 minute cities.”

Totally the same

American liberalism began to lose its way in the 1960s. For the first time, a generation of young people, particularly young men, went to college in large numbers. They did so at the exact moment in history when the American academy was being deeply influenced — one might say infiltrated — by European Marxists, anarchists, and other radicals, the likes of Louis Althusser, Herbert Marcuse, Jean-Paul Sartre, Antonio Negri, Michel Foucault, and a host of others.

These armchair revolutionaries preached class warfare and proletarian uprising. To vulnerable young minds, they explained everything from segregation to the war in Vietnam. It was heady stuff. It was also almost uniformly wrong.

No matter: The die was cast. For the next six decades Marxism and anarchism spread through the academy like a cancer. We’re going on a fourth generation of college graduates who spent four, five, or more years imbuing the tempting rhetorical ambrosia of romantic revolution. Those graduates became professors themselves, they became writers, creators, and inventors. More than a few of them became business leaders. As a consequence the Marxist lexicon is now second nature, so much so that many of us don’t even notice. We don’t talk about “employees,” we talk about “workers.” We compare “capitalism” to “socialism,” often negatively. We have a “labor movement.” And, of course, we accept as received wisdom that one’s class largely determines their destiny.

Whether we can unteach ourselves some of this language remains to be seen.