Blog Post < Previous | Next >

The Organic Chemistry Tutor

The Real Affordability Crisis

“Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth” ~ Joseph Goebbels.

Last week, I wrote about the dismal track record of California’s state housing laws to increase the construction of new housing and the formidable economic headwinds that legislators don’t seem to understand. But, this is only half the story.

Politicians in Sacramento have been wailing on local governments about the need to build “affordable housing” as a scapegoat to avoid dealing with their own public policy failures. In addition to attacking local control of planning and zoning laws, they are even trying to eliminate the citizen’s ballot initiative process in the single-minded belief that their policies are the only answer. But, what if they are just plain wrong?

I’m not talking about the fact that the State Auditor’s Office says Sacramento’s estimate that we need to build 3.5 million homes is a work of fiction (Freddie Mac estimates that the US housing market faces a shortfall of 3.8 million units of housing, so how can California need almost all of them) or that California’s Governor has turned a blind eye to the facts and chosen instead to rely on ginned up studies by international think tanks that are little more than marketing arms for corporate interests.

I’m asking a simpler question. What if the affordable housing “crisis” isn’t the disease but only a symptom of a bigger disease?

The Decimation of the American Middle Class

By now, everyone is familiar with the fact that the disparity between what a CEO of a major corporation makes annually and what the average worker in the average major corporation makes has increased in the past 70 years. But, that disparity has reached epic proportions.

According to Forbes magazine, that disparity was about 20 times in the 1950s (the average corporate CEO made 20 times what their average worker made). As of today, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, the average CEO makes 670 times what their average employee makes.

While executive pay has sky-rocketed, enhanced by stock options and a myriad of other perks, the average worker’s plight has gone in the opposite direction.

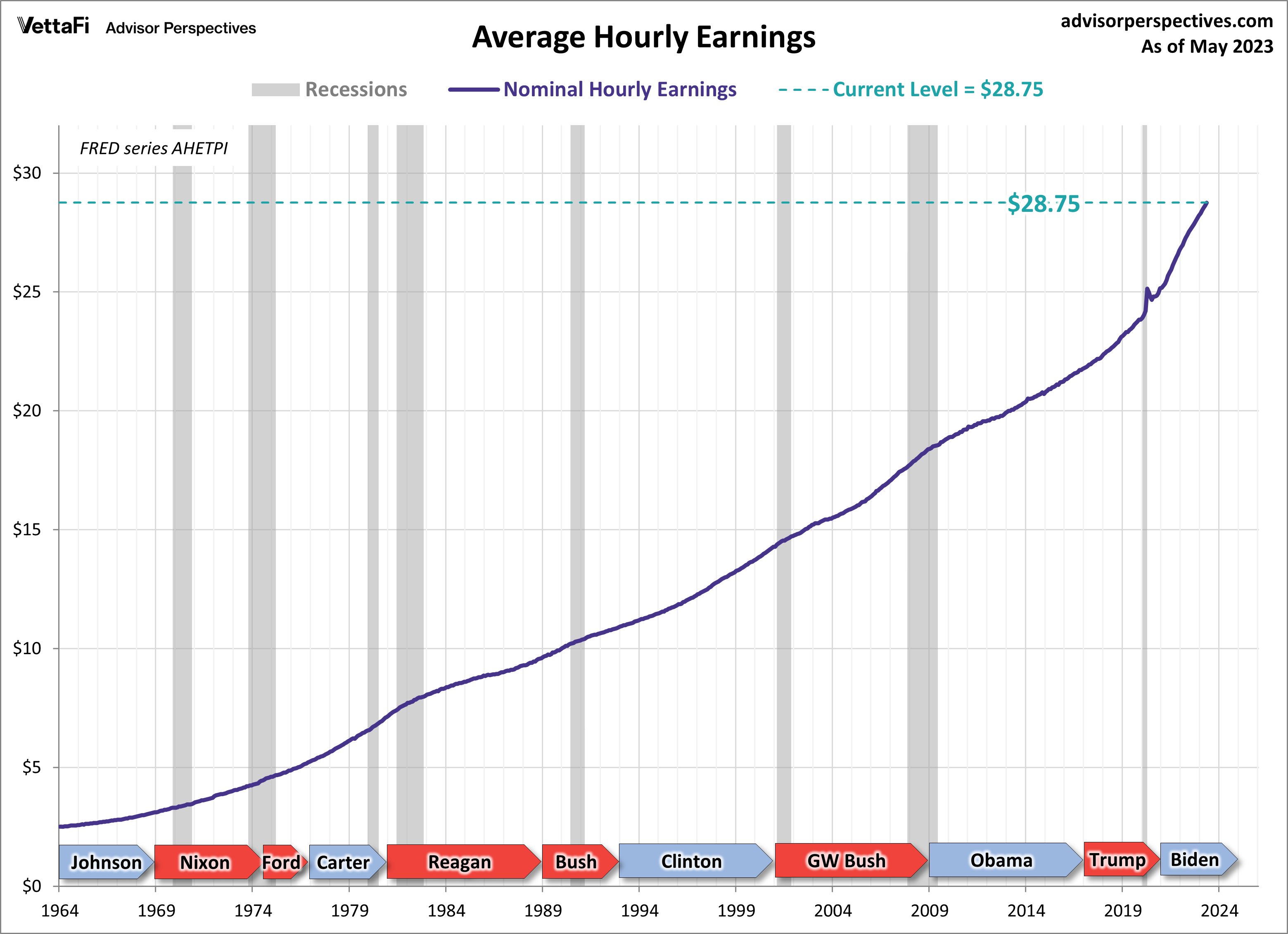

The chart above shows the “nominal” gains in hourly earnings for the average employee in the U.S. On its face, it appears that worker wages have been rising steadily. But, that’s an illusion.

The chart below tells the “real” story.

The hourly earnings of the typical employee in the U.S. have not risen in real, inflation-adjusted terms in decades. (The recent momentary spike above that came in 2020 was when statistical data became skewed by the collapsing economy before inflation took hold.)

As noted by economist Jennifer Nash,

“The Bureau of Labor Statistics has been collecting data on this workforce cohort since 1964. The latest hypothetical real (inflation-adjusted) annual earnings are at $48,588, down 8.0% from 50 years ago.”

Meanwhile, let’s look at housing prices during the same period.

The data above is stunning, even though it’s an approximation because (1) it shows national averages for housing prices, whereas California’s housing prices have moved up faster in the past decades, and (2) the data is more than a year old, and home prices have fallen a bit in 2023, but the overall trend and percentages are undeniable.

“Real,” inflation-adjusted housing prices have gone up at least 100 % since the 1950s (probably 150% in California) while “real” inflation-adjusted wages have gone nowhere. It doesn’t take a room full of PhD's, then, to understand why the average working middle-class family can’t afford a home and has fallen so far behind that they may never catch up.

To put this another way that will help appreciate the magnitude of this affordability divergence, consider that if real wages had even risen by 5% in the past 50 years (which they haven’t), housing costs would still have risen more than 20 times that much, or 2,000% more over that same period, irrespective of temporary supply and demand constraints, booms and busts, high interest rates and low interest rates, varying costs of construction, or anything else.

That considered, how could we not end up with an affordability problem?

Nay-sayers may still argue that housing costs are rising faster because we have not built enough, today, which might make sense if our “unaffordability” phenomenon was confined to housing, but it’s not. It is everywhere and in all things.

The disparity between inflation-adjusted wages and the dramatic rise in the costs of living for most middle-class family necessities, including healthcare, insurance, groceries, energy costs, and a college education are equally out of whack. And, there have been no persistent supply/demand issues to explain those affordability disparities, over time, other than those created by government policies and grossly inequitable tax laws.

Meanwhile, the accumulation of personal debt is rising rapidly, evidence that people are going deeper into debt to maintain their lifestyle, even in the face of rising interest rates when it’s the worst time to go into debt.

(The only savings grace is that a substantial portion of the mortgage debt accumulated in the past few years has been at historically low interest rates, which is not true for credit card debt, auto loans, or student loans, where delinquencies are rising rapidly).

Again, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to understand that servicing that debt makes it much harder to save up for a down payment to purchase a home or to pay rent. How does building more housing increase real wages or reduce personal debt?

Housing isn’t really unaffordable for the average family because of its price. Housing is unaffordable because people don’t make enough money to afford it. And the charts above indicate that this discrepancy is now increasing exponentially.

The question is, why?

It appears that our system is just not working for an increasing number of people. It is not educating them, feeding them, keeping them healthy, or offering them opportunities to get a leg up. At the same time, state and national politicians are digging in their heels and defending their status quo and the protocols and procedures that protect their fiefdoms and powers. The dysfunction is palpable.

As a result, anxiety and resentment are rising, while the all-consuming blame game that has taken over political discourse is leading everyone off into the weeds.

It would be a huge mistake to ignore all this in the belief that things will just work themselves out. However, there is yet another twist to this conundrum. The inequity we’re seeing around us may be the result of larger forces that are not fully being considered in the calculus.

The chart below was compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. I think it woefully underestimates the magnitude of the jobs that will soon become obsolete but it’s a place to start.

There’s little doubt that basic service and administrative jobs are being rapidly replaced by computers, software, and robotics. But, this particular estimate was done before the advent of the machine learning/neural network/artificial intelligence (“AI”) phenomenon that is suddenly deconstructing all our ideas about work. When you add AI’s potential into the mix, there is hardly a profession we know of that won’t be able to reduce a sizable percentage of its workforce.

(Ironically, coding, once-considered a bulletproof skill, may be one of the most impacted professions of all.)

When I opened a small architecture practice more than 40 years ago, I had a staff consisting of a receptionist, a bookkeeper/payroll person, an executive secretary, and several architects and draftspersons. In addition, we relied on a bevy of consultants for model building, presentation renderings, various types of engineering, tax preparation, and even a tech consultant to help us “install” office “PCs” and printers when they first became available. Everything had to be printed, physically delivered, mailed, or FedExed, and communications involved a lot of physical meetings.

Today, our nonprofit, Community Venture Partners, has its bookkeeping automated on Quickbooks and its tax and accounting done by an online firm for less per year than our executive secretary was paid for a day’s work (without even adjusting for inflation). Everything is sent electronically, “reception” is voicemail, computers and printers are plug-and-play, and presentation and CAD software are so fast and ubiquitous that anyone can create presentation materials from anywhere in the world.

In sum, one skilled person can now produce almost the entire work output of that office staff in significantly less time.

All this will not happen overnight, but as “AI” matures and it integrated into our workflow, the need for a few highly skilled people will increase disproportionately, but the need for all other workers will be dramatically reduced. What happens to all those individuals—uneducated or unskilled or too old to change--caught in this historic disruption that began with the arrival of personal computers, was super-charged by the advent of the Internet, and is about to launch us to almost inconceivable heights as AI and quantum computing transform the definition of a "job?"

How can an economy, predominately made up of service jobs and knowledge workers, an economy which has already largely automated the actual production of “things,” survive this job destruction? Without robust, middle-class participation in our economy, housing our population will be impossible.

In that context, one has to ask if housing unaffordability is really being caused by not building enough housing or is it a consequence of ongoing rapid change, dislocation of capital, and a societal metamorphosis: a gigantic socioeconomic caterpillar shedding its old skin to be reborn and something entirely new?

These are not just academic questions. Because if this is what’s really going on, we need to stop pointing fingers and quickly work together to address these challenges in completely new ways. Barring that, we risk everything getting out of hand and unimaginable, negative consequences, which more and more include severe environmental impacts.

Yes, we can do things to alleviate income inequality. Anyone who is making over $10 million a year who thinks they can’t afford to pay more taxes does not have a tax problem, they have an emotional problem that needs professional help. But these kinds of relatively minor adjustments aside, what someone is paid will always remain tethered to that person’s economic output value. And that can’t be “socially engineered” away by political rhetoric or some fashionable ideology.

As important as all the crises that we hear about in the “news” may feel, most of the problems society is currently squabbling over are not the ones that matter. We are in danger of becoming so wrapped up in our personal hopes and dreams and fantasies and responsibilities and needs and feelings and fears and hatreds in the moment that we risk losing the ability to see more than a few feet in front of us.

But the future will be here faster than we think and the odds that we will be prepared for it are not looking good.

Bob Silvestri is a Marin County resident, the Editor of the Marin Post, and the founder and president of Community Venture Partners, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit community organization funded by individuals and nonprofit donors. Please consider DONATING TO THE MARIN POST AND CVP to enable us to continue to work on behalf of all California residents.