Blog Post < Previous | Next >

Michael Barnes

Why you shouldn't trust the NY Times on California housing

On Oct. 4, this editorial, “California is Actually Making Progress on Building More Housing,” appeared in the online version of the New York Times. The author is editorial board member Binyamin Appelbaum. It was so full of errors and misconceptions that I felt obligated to respond.

I wrote this rebuttal for two reasons. First, I wanted to set the record straight on many contentious housing issues that newspapers such as the NY Times, the LA Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle deliberately distort. Second, I want to stress that these mainstream newspapers are unreliable and that you should be skeptical of the competence and the intentions of their editorial boards.

The article contains links to cited documents, which you also find in the PDF version here: bit.ly/3Fy3CEN

Excerpts of the story appear indented and in quotes. My comments are inserted below each.

My rebuttal

"One big reason for the chronic housing shortage in America’s most prosperous regions is that state governments have ceded control to local governments that behave like private clubs."

As corporate developers have grown in size and influence, they have begun to chafe at dealing with a multitude of local governments with their variety of regulations. Big developers would prefer to deal with state governments, where they can focus their resources and more easily buy influence.

California’s 482 municipal and 58 county governments are not anything like private clubs. They have open borders with no entry requirements. Under California’s Brown Act, city council deliberations are held in public. The state legislature in Sacramento is far less accessible. At the State Capitol, most deliberations are made in private, and legislation is lobbyist-driven.

The idea that California’s state legislature is more devoted than its local governments to serving the public interest is ludicrous. But while both local and state governments can be far from perfect, the real private clubs are California’s powerful, unelected corporate organizations like the Bay Area Council and the Silicon Valley Leadership Group.

But none of this is new. As eminent UC Berkeley economic geographer Richard Walker noted in a 1981 paper, “Contrary to the reformers’ claims, large-scale residential developments are not demonstrably more efficient, equitable or environmentally sound than small ones.

Similarly, state or regional intervention is, depending on political forces, as likely to suppress popular democracy and valid public goals as to serve them.”

"The state’s political leaders are clearing the way for housing construction by restricting local interference, prioritizing the needs of all Californians — and those who might like to be."

This is not true. “All Californians” include those low-income residents who need affordable housing. The state has been failing to prioritize deed-restricted and other forms of affordable housing for years. When Governor Jerry Brown ended redevelopment funding during the Great Recession, local governments lost their main source of affordable housing subsidies.

This has made local governments convenient scapegoats for Sacramento’s failure to prioritize funding. State Senator Jim Beall (now termed out of office) was one legislator who tried to create a stable source of affordable-housing funding. In 2019 his bill, SB 5, redirected property tax revenue to create a permanent source of revenue. Although supported by cities, labor, affordable housing groups and Beall’s fellow legislators, SB 5 was vetoed by Governor Newsom.

"The California Legislature has passed a set of bills that shift the balance of power toward building. Among the latest batch, signed into law over the last few weeks by Gov. Gavin Newsom, are bills easing the conversion of commercial buildings into homes and banning parking requirements for housing and retail developments near public transit."

Appelbaum first refers to two bills, SB 6 (Caballero) and AB 2011 (Wicks). They take different approaches to encouraging residential construction in retail and commercial buildings that are underutilized post-Covid. Attempts to reconcile the two bills failed, so both were passed, leaving developers and local governments to sort them out during the next several years. The third bill mentioned, AB 2097 (Friedman) is elitist. It bans local governments from requiring parking spaces in any residential or commercial project within half a mile from public transit — even if the transit is just the intersection of two major bus routes that run every 15 minutes during commute hours.

Lower-income workers need cars and places to park them. They typically cannot work from home or use public transportation. They are often construction workers, home health care aids, house cleaners or retail and services sector workers who do shift work. Developers would rather have residents use street parking since this just shifts costs onto the public. But adding parking is not that expensive.

Let’s assume a parking spot costs $60,000 for a builder and that the cost is spread over the 50-year life of the building. That’s $100 a month or about $3.33 a day. Most people in urban California would be willing to pay $3.33 for a parking space in their building, especially if they had the option to lease the space to someone else.

AB 2097’s author, Laura Friedman, enjoys the typical privileges of legislators and older self-appointed urbanists, the majority of whom live in single-family houses. In Friedman’s hometown of Glendale, 63.6 percent of the housing units are apartments, and 74.8 percent of the workforce drives alone to work (2016-2020 American Community Survey). If the residents of Glendale couldn’t park in their own buildings, where would they park and how would they drive to work?

"Mr. Newsom’s administration is working to enforce the laws, as the Times reporters Conor Dougherty and Soumya Karlamangla detailed in a recent article. One example of the state’s enforcement efforts: A landmark measure passed in 2021 allows at least two homes on most residential lots, but cities quickly fought back by imposing absurd requirements on those seeking to build new housing. Among the crazier ones cataloged by The Times: “A covered porch, the signature of an archaeologist, the highest level of energy efficiency and an automatic garage door.”

This is a reference to SB 9 (Atkins). In addition to allowing two units on a single-family lot, it also allows the lot to be split and the construction of two more units with a minimum size of 800 square feet each on the undeveloped lot — even on lots as small as 1,200 square feet. The criticism that some requirements are “absurd” and “crazy” are unfounded without knowing more about their context.

Strong energy standards are often required in new construction in California. An archeology review is common, at least for larger projects, in regions where shell mounds or other native American artifacts and remains could be found. Automatic garage door openers make garages accessible for children, seniors and the disabled.

This is especially important in case of a fire when the garage door may be the safest exit. And covered porches could be part of local design standards, which are allowed under SB 9.

"Woodside, a wealthy town in Silicon Valley, barred duplex construction by declaring the entire community a protected habitat for mountain lions. The state’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, responded with a warning. “My message to Woodside is simple: Act in good faith, follow the law, and do your part to increase the housing supply,” Mr. Bonta said. “If you don’t, my office won’t stand idly by.”

Appelbaum misstates the issue. SB 9 is a messy bill. Nowhere in the bill’s text do the words “protected,” or “habitat” appear. At the time of its first decision to suspend implementation of SB 9, Woodside was simply following the plain text of the law, which according to SB 9 provides exemptions as specified in subparagraphs (B) to (K), inclusive, of paragraph (6) of subdivision (a) of Section 65913.4 of the California Government Code. According to paragraph J, a property is exempt from SB 9 if it is on a site with:

(J) Habitat for protected species identified as candidate, sensitive, or species of special status by state or federal agencies, fully protected species, or species protected by the federal Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. Sec. 1531 et seq.), the California Endangered Species Act (Chapter 1.5 (commencing with Section 2050) of Division 3 of the Fish and Game Code), or the Native Plant Protection Act (Chapter 10 (commencing with Section 1900) of Division 2 of the Fish and Game Code).

Newsom and Bonta didn’t like the breadth of the SB 9 habitat exemption, so they used their influence with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which earlier had included Woodside in maps of mountain lion habitat. After discussions with Bonta’s office, the department changed its mind and issued a ruling that not all of Woodside could be considered habitat.

Unfortunately, Bonta is wrong on the science. By scientific and conservation standards, Woodside is mountain lion habitat. Bonta joins a long list of politicians who distort scientific findings to suit their political agenda. This is disappointing. See these three documents for more information. Two are City of Woodside documents (here and here). This document is an opinion from a conservation scientist (here).

A quick view of Woodside’s expansive open space on Google Maps reveals why another group disagrees with Bonta — the mountain lions. Despite the controversy, they will continue to assume Woodside, its neighbor Portola Valley and the surrounding areas are their habitat.

The events in Woodside took place in late January and early February. By April, Bonta was involved in another SB 9 conflict, this time with the City of Pasadena. SB 9 had created another broad exception for historical and landmark districts. The attorney general attacked Pasadena, but he was wrong to do so. So was the LA Times, which produced a snarky but incompetent editorial.

The city easily showed that its historic and landmark districts, some in place for decades, had met the state and federal guidelines. The letter from the city attorney to the attorney general is worth reading. Bonta worked out a face-saving compromise, but the reality is that he didn’t know the law when he began making unfortunate public comments, and in the end, he lost.

The ironic denouement of this SB 9 story is that the bill probably won’t make much difference. According to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation’s study of SB 9, “Relatively few new single-family parcels are expected to become financially feasible for added units as a direct consequence of this bill.”

According to this recent SF Chronicle article, “SB 9 has had limited impact in San Francisco since it went into effect at the start of the year. Fewer than 30 projects have applied using the new law and just three have been approved by the planning department.”

"One of the earliest pro-housing measures that California passed, in 2016, sought to make it easier to add a garage or basement apartment to a single-family home. Local governments tried to undermine that law by allowing applications to pile up, imposing exorbitant fees and writing clever restrictions.

"In 2015, local governments issued 1,205 permits for the construction of accessory units in California. In 2020, the most recent year for which comprehensive data is available, 12,569 permits were issued, according to an analysis by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. And the state has since passed a law seeking to make it even easier to build such units."

The bill, SB 1069 (Wieckowski), not only “sought to make it easier to add a garage or basement apartment,” It explicitly included accessory development units (ADUs). The number of issued permits cited above, 12,569, also requires some context. According to the California Department of Finance Demographic Research Unit, as of April 2020 the state population was 39,538,223 while the number of housing units was 14,392,140. Thus in 2020 there was one issued ADU permit per every 3,146 residents and 1,145 housing units.

However, not every permit results in a new structure, because not all permitted projects are completed. In addition, post-Covid, many ADUs are used as work-from-home offices. Others might become guest quarters, Airbnb short-term rentals, rec rooms, or the teenagers’ bedrooms.

Most are built in high-income areas, at least in Seattle and San Francisco, although this study by the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) paints a more nuanced picture. Many ADUs do not become formal rental units, and certainly not affordable units.

"Mr. Newsom was elected in 2018 on a platform of full-throated support for more housing, declaring that the state needed a “Marshall Plan for affordable housing.” He set a goal of 3.5 million new housing units by 2025, consistent with expert estimates of the state’s need. Meeting that goal would require 500,000 new housing units annually, but last year, in 2021, local governments issued permits for only about 120,000 units. Mr. Newsom’s unrealistic rhetoric should not overshadow the state’s progress."

The 3.5 million figure was based on a questionable calculation by McKinsey consultants. The real experts work in the Department of Finance Demographic Research Unit, and their projections of households (see P-4 here), which are the basis for the projections for housing units, are much lower. It is misleading to state that local governments issue permits. It is up to developers to pull permits.

The process is driven by developers, not local governments. The production of market-rate housing is based on market conditions and profitability. Except for publicly subsidized affordable housing, it is markets that determine the amount of housing, not governments.

"To take one indicative measure, for every 100 lower-income families that rent housing in California, there are about 60 units of affordable housing available, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. In New York — a state that is in the throes of a serious housing crisis by any metric except “Are We Doing Better Than California?” — the comparable figure is still 84 units. (That is, in part, because housing remains more affordable outside of the New York City area, and because New Jersey eases pressure in the metro area by allowing construction along the west bank of the Hudson.)"

It is odd that the west bank of the Hudson is mentioned. According to this NY Times article the west bank of the Hudson is now the most expensive rental market in the U.S. Perhaps now rentals in NY City ease the pressure on Jersey City rents.

One major difference between California and New York is that in California, there is more rural poverty than in the State of New York. New York state does not have an agricultural region on the scale of California’s Central Valley with a large workforce of undocumented farm workers. But for perspective, here are the percentage of rental cost-burdened households in the U.S. and three large states (2015-19 ACS). A household is considered cost burdened if it spends more than 30 percent of its income on housing expenses, including utilities. The affordability crisis is national. In descending order:

55% California

52% New York

50% U.S.

48% Texas

"The crisis also is starkly visible in California, where tens of thousands of people who cannot afford stable housing live in doorways, in their vehicles or in tents pitched on open land."

Yes, but that is also true of Seattle and Portland. NY City has more homeless (78,604) than Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley combined. Los Angeles and NY City have similar numbers of homeless on a per capita basis. The percentage of housing cost-burdened renters in San Francisco is 36.7 percent. In New York City it is 52.1 percent (2016-20 ACS). However, NY City does a much better job of keeping the homeless in shelters. But then Los Angeles has much milder weather.

Housing per se isn’t sufficient to solve the homeless problem. There is a difference between getting people housed and keeping them housed. Many homeless with drug abuse and mental health problems struggle to stay housed.

"And the rise of the tech sector has helped to reshape the politics of housing. Some of the new billionaires may not care how the other half lives, but others, believers in technocratic solutions to social problems, have embraced the proposition that the solution to a housing crisis is more housing. They have pumped money into research, lobbying and lawsuits, constructing a professional class of advocates.

"California YIMBY, founded in 2017, got much of its early funding from the tech industry, including $1 million from the online payment company Stripe. “The dearth of available and affordable housing is a significant barrier to the Bay Area’s economic progress,” the company’s chief executive, Patrick Collison, said at the time. “We think broad policy change will make the most meaningful, widespread and long-term difference in the state’s housing crisis, by allowing developers to build more housing — specifically lower-cost, higher-density housing.”

Appelbaum states that new billionaires are “Constructing a professional class of advocates.” It’s more accurate to say that California YIMBY bought its staff. And “advocates” is a euphemism for lobbyists. California YIMBY uses the services of existing lobbying firms (to see this, click on the link and enter “yimby” as the company name in the search feature). There is nothing technocratic about that. Was Tammany Hall technocratic?

Collison and the YIMBYs make a serious mistake by calling for “lower-cost, higher-density housing.” That is an oxymoron. Density is positively correlated with higher rents. In San Francisco the struggle against density and Manhattanization flourished in the 1980s and resulted in the passage of Proposition M, which restricted the growth of downtown office space. This is not a new issue.

The tech sector is self-interested. Reducing housing costs for their workers would allow them to pay lower salaries, increasing their profits. The affordability crisis calls for subsidized housing for lower-income households. YIMBY support for this has been tepid and opportunistic. “Build baby build” does not refer to deed-restricted affordable housing.

The YIMBYs are a minor league farm team for the Bay Area Council. Louis Mirante, the former Legislative Director of California YIMBY, was recently hired as the Vice President of Public Policy by the Bay Area Council. Here’s an example of a YIMBY group that worked closely with the Silicon Valley Leadership Group.

At an early YIMBY national conference, California State Senator Scott Wiener, with his strong ties to the Bay Area Council and the real estate industry, referred to the YIMBYs as “our shock troops.” (Overheard and noted at a 2017 YIMBY conference by author Zelda Bronstein).

"Cities have deep pockets to resist the state laws; this tech-sector money means that proponents now have deep pockets, too."

The Bay Area Council, real estate interests and big tech have always had deep pockets. It is grossly misleading to say that California’s 482 cities have deep pockets, or that they use them to resist state laws. Many cities struggle to provide basic services and to set money aside for unfunded pension liabilities. Perhaps Appelbaum could prepare a list of cities and counties in California that he thinks have deep pockets.

"One of the most important tools in California’s arsenal is a law requiring local governments to make room for enough housing to meet projected demand. The law lacked teeth until it was modified in 2017."

Appelbaum is referring to the Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA). This process has always been a nearly useless but very expensive unfunded mandate for cities. Every eight years even small cities must spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in staff and consultant hours to prepare these reports. In 2018, State Senator Wiener carried SB 828, a bill sponsored by the Bay Area Council and the Silicon Valley Leadership Group. This bill helped create new and wildly unrealistic RNHA housing targets.

"Shortly after Mr. Newsom took office in January 2019, his administration became the first to take action under the strengthened law, suing the Orange County city of Huntington Beach. The city had created a plan in 2015 that included room for 413 units of affordable housing. Then, in response to local opposition, it reduced that number to just 70. Huntington Beach settled the case by agreeing to allow the construction of more than 500 units of low-income housing. In an interview last month, Mr. Newsom said the lawsuit was meant as an early demonstration of his “fanatical intention” to increase the supply of housing in California. “It’s a question of political will,” he said."

It is not a question of political will, regardless of what Newsom thinks. Newsom’s predecessor, Gov. Jerry Brown, was far more skeptical that the legislature could reshape housing markets. Regarding Huntington Beach, I’ve read many versions of this story. Huntington Beach is the poster child for resistance to Sacramento. It is an exception.

It’s a conservative city, a throwback to the days when Orange County was a Republican stronghold. Compare Huntington Beach to San Francisco. According to housing advocate Calvin Welch:

A full 63 percent of San Francisco’s current housing stock is price controlled, either by local, state or federal regulations. In 2015, 242,000 of San Francisco’s 383,000 units were price-controlled:

- Rent control: 174,000 units

- Non-profit developed permanently affordable housing: 31,000 units

- Below-market units: 2, 300

- Residential hotel rooms: 19,000 (either non-profit or unable to be converted to market rate)

- Section 8 vouchers: 9,500 units

- Public housing: 6,000 units

Appelbaum repeatedly makes the mistake of painting all California cities with the same brush. It makes no sense to lump together two California cities as different as Huntington Beach and San Francisco.

"The state has created a Housing Accountability Unit to pursue similar cases. The budget is only about $4 million a year, but Jason Elliott, a senior adviser to Mr. Newsom on housing issues, said that by holding local governments accountable, the unit could facilitate more construction than the billions of dollars the state spends annually on building subsidies. In August, the unit announced an investigation of San Francisco, where it takes an average of 975 days to obtain a construction permit — when one can be obtained at all."

Since the end of redevelopment funding in the Great Recession, the state has not consistently spent billions of dollars “annually on building subsidies.” It did spend billions on Covid related programs, but this was one-time money. See this, more here. Care must be taken when assigning blame for the length of time it takes for developers to pull permits. Delays can be caused by both the city and the developer.

Contrary to what Appelbaum stated, in San Francisco developers have pulled many building permits. The State Dept. of Finance shows that San Francisco added approximately 4,500 housing units in 2022, and 4,100 the previous year. Almost all of these were in multi-family buildings.

"Mr. Newsom’s will for battle is not boundless. Shortly after taking office in 2019, he proposed withholding state transportation funds from communities that failed to meet housing goals. It is a sensible idea, echoing President Biden’s proposal during the 2020 campaign to condition some federal infrastructure funding on changes in local zoning to allow more construction."

This was not a sensible idea, it was an arrogant, unforced error by Newsom. In 2017 State Senator Beall (D-San Jose) authored SB 1, a transportation funding bill that relied on increasing the state gas tax. The bill was carefully constructed to build broad support and promised to dedicate all the new gas tax revenue to transportation projects.

The bill caused an uproar among anti-tax conservatives, and an Orange County Democrat who voted for the bill, Josh Newman, was successfully recalled (he later ran again and won his old seat back). Next, a voter-initiated ballot measure, Proposition 6, was placed on the Nov. 2018 statewide ballot to rescind the gas tax. The initiative failed.

After all the work to pass the original bill and fight off the initiative, Newsom stepped in and clumsily threatened to withhold gas tax revenue from cities that did not meet his housing goals. That caused another uproar. Newsom’s idea was denounced by both Republicans and Democrats. Patricia Bates, Orange County Republican and former Senate Republican Leader, called it a bait-and-switch. Newsom withdrew the idea.

"But the willingness of California’s state leaders to override the obstructionist proclivities of local governments in the service of the broader public interest is making a real difference. Similar courage is needed from political leaders in New York and other states where it has become unreasonably difficult to build housing in the places where people want to live."

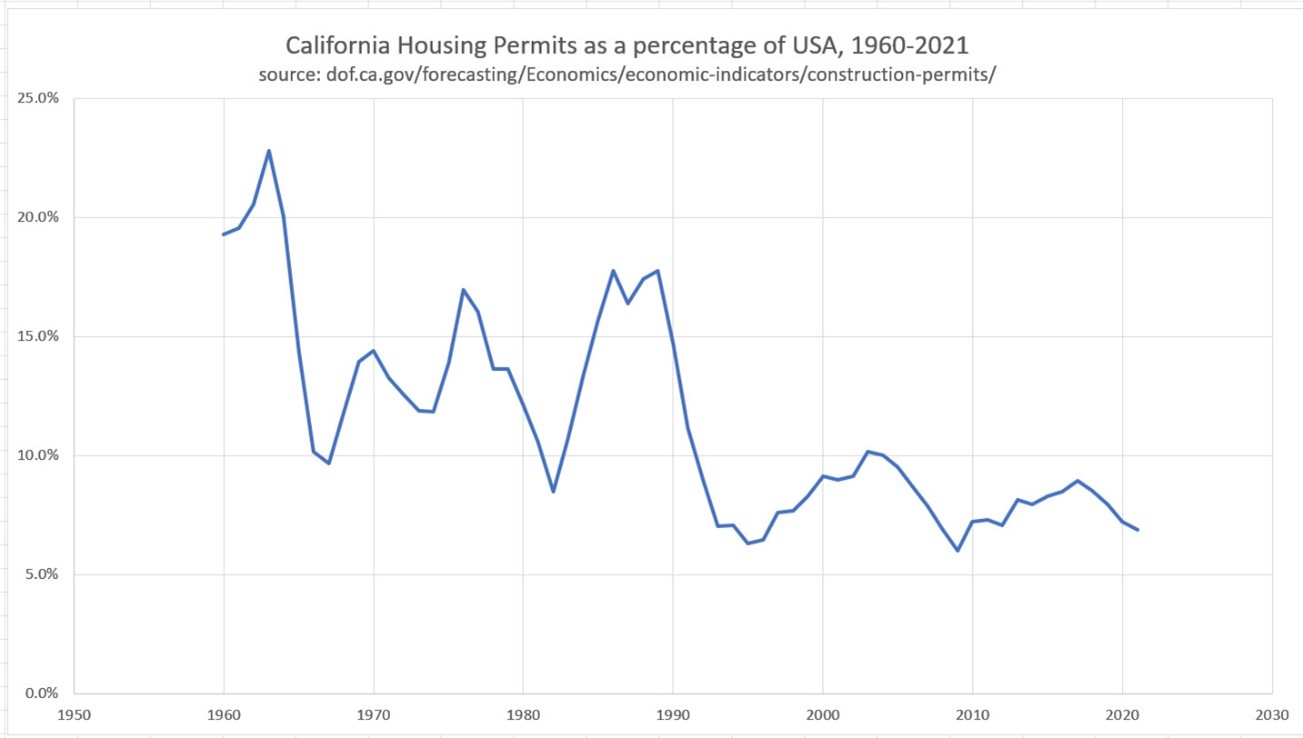

It is difficult to critique Appelbaum’s final statement above because he seems to inhabit an alternative reality, one that he has made up from scraps of news and opinions that he has glimpsed, like the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave. But from the graph below (data here), it doesn’t appear that California’s residential building sector is rebounding, at least not compared to the rest of the United States. The graph starts its most recent decline in 2017, the year of the first 15-bill housing package in Sacramento, when the torrent of housing bills began.

Applebaum’s editorial is condescending, intellectually lazy, and credulous. He would have benefited from hiring a few internet-savvy students to do some fact checking for him. But why bother to check facts when you already know what you are going to write?

There is nothing courageous about Gov. Newsom and the legislative leaders who genuflect to private corporate organizations like the Bay Area Council and the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, developers, big banks and the landowners who envision endless economic growth. Their goal is growth, not rectifying California’s affordability crisis.ABOUT MICHAEL BARNES

My

background: After earning my B.A. and M.A. in economics in the early

1980s, I served for 2.5 years as a budget and economic analyst for the

State of Washington in Olympia, WA. I came to Berkeley in 1989 as a

Ph.D. student in economics, but my interest in the social sciences faded

while my interest in the physical sciences grew, so in 1996 I switched

career paths and joined the UC staff.

I retired in 2017 after spending the final 11 years of my UC career as the science editor for the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry. The College is immensely proud that the last three of the seven female winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry — Francis Arnold (2018), Jennifer Doudna (2020), and Carolyn Bertozzi (2022) — were all either students, faculty members, or both at the College. I have had the privilege of interviewing and writing about all three.

I served on the Albany City Council from 2012 to 2020, and I stay involved with local govt. issues. Finally, as an avid cyclist, I have cycled or walked in 42 of California’s 58 counties, traveled by car through another 13, and have failed to visit only three.