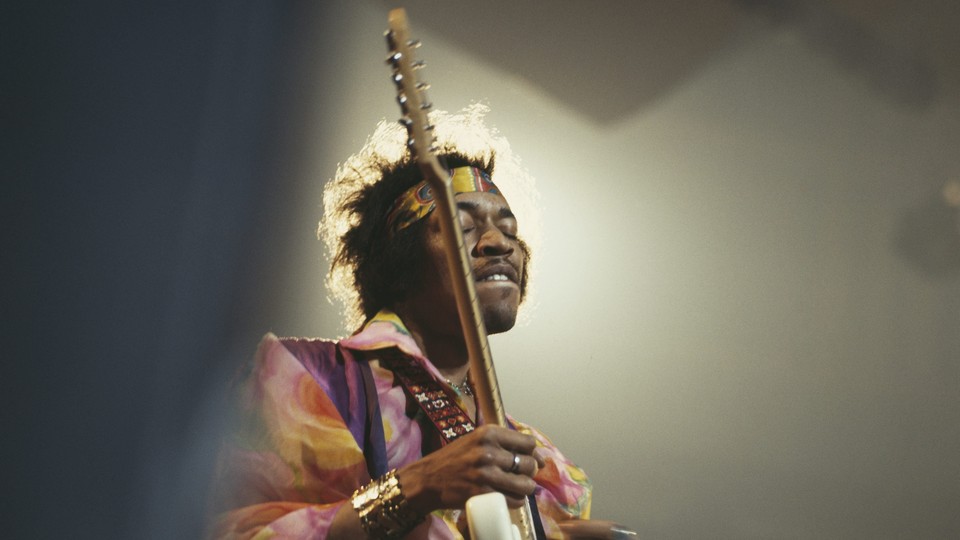

How Jimi Hendrix’s London Years Changed Music

A new book retells the artist’s fairy tale—rising out of deprivation to storm the spires of rock and roll—by considering his influence on the U.K.

“It’s so lovely now,” Jimi Hendrix said in his muzzy mumble, his topplingly elegant, close-to-gibberish, discreetly space-traveling undertone, onstage one night in 1967 at the Bag O’Nails in London. “I kissed the fairest soul brother of England, Eric Clapton—kissed him right on the lips.”

This is one of many groovy scenes recorded in Philip Norman’s new Hendrix biography, Wild Thing. The fairest soul brother, we can be sure, was transported. Hendrix had arrived in London a year earlier, with not much more than the clothes he stood up in, and immediately induced holy dread in the city’s top guitarists. “There were guitar players weeping,” reports the singer Terry Reid of one early Hendrix performance. “They had to mop the floor up. He kept piling it on, solo after solo. I could see everyone’s fillings falling out.” And of them all, Clapton was the toppermost: CLAPTON IS GOD read the spray-paint legend on a wall in North London. Hendrix, who—let’s be real—could have destroyed Clapton with a flick of his wrist, was all humility: He reverenced Clapton’s work in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and (especially) Cream. Clapton, terrified at first—“You never told me he was that fuckin’ good,” he protested to Hendrix’s manager, Chas Chandler, over a wobbling backstage cigarette—fell swiftly and properly in love.

As did everybody else. The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, at every Jimi Hendrix Experience show he attended, would punctually weep for joy: “In whatever dark London vault the Experience played,” writes Norman in a particularly beautiful sentence, Jones “would be visible as a dual glint of blond hair and tear-wet cheeks.”

Norman is a veteran music journalist and biographer, best known for 1981’s Shout! The Beatles in Their Generation, a classy piece of Beatleology that was nonetheless renamed Shite! by a less-than-thrilled Paul McCartney. Wild Thing is good on Hendrix’s meteoric impact on Swinging London (and then the world), the crater he left in consciousness. It’s not quite as good on the precise electric-acoustic dimensions of that crater. But that’s always the challenge with Hendrix: How to describe, how to even verbally gesture at, the extraordinary sounds he made? Or to reconcile this diffident, melancholy man with the Promethean audacity of his art? The best analysis in the book, rather poetically, comes from an unnamed Finnish journalist quoted by Norman, who reviewed a Hendrix show in 1967 and heard “a voice from the reality of today’s worldwide information network that effectively spreads both terror and delight.”

The other challenge with Hendrix—a challenge for us, now—is to part the beaded curtains and the veil of dope smoke, to pierce the purple haze and reckon with him politically, aesthetically, and culturally as a Black artist in his time. Charles Shaar Murray did a musicologist’s version of this with 1998’s Crosstown Traffic: Jimi Hendrix and the Post-war Rock’n’Roll Revolution, but the canon of Hendrix biography, in my opinion, still awaits a book with the historical heft and acumen of David Remnick’s King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero—a book, in other words, capable of mapping the larger forces of which Hendrix was the electrified nexus.

Hendrix came out of the blues, but he harnessed feedback; he cut his teeth as a road guitarist with Little Richard and the Isley Brothers, but he was drawn to the spaciest frontiers of acid rock, which he transgressed and then exploded. Courted by the Black Panthers and the subject of an FBI file, he was a Black man whose most urgent communications to America were made in the form of heaven-scraping noise. Racism is almost a fully formed character in Wild Thing, popping up all over with demonic buoyancy, here in a thoughtless characterization from a ’60s journalist (“Jimi ... could pass for a Hottentot on the rampage”), there in the menace of the segregated South, which Hendrix knew from touring. Norman is sensitive to the racial context, except when he isn’t. A passing portrait of the young Clapton gives rise to the most regrettable sentence in the book: “Blues music had rescued Clapton from despair in leafy Surrey as surely as it had any beaten and starved Mississippi slave.”

Where Wild Thing succeeds, sometimes spectacularly, is in its retelling of the Hendrix fairy tale: the story of little motherless “Buster” Hendrix, pigeon-toed from years of too-small shoes, rising out of deprivation and the blue-cold Seattle winter to storm the spires of rock and roll. The details have a strange glimmer—neglectful Al Hendrix, as if anticipating his son’s otherworldly dexterity, is born with an extra finger on each hand. Music chases the boy from the beginning: “He’d tell Grandma he had all these weird sounds in his head,” his brother Leon tells Norman, “and she’d swab out his ears with baby-oil.” In early manhood, he joins the 101st Airborne, and experiences the trippiness of jumping out of airplanes. “It’s almost like blanking and it’s almost like crying,” Hendrix says later, “and you want to laugh. It’s so personal because once you get there it’s so quiet.” Then he hits the road with his guitar. Writes Norman, “Curtis Mayfield expelled him for accidentally damaging an amplifier. On tour with Bobby Womack, his behavior was so exasperating that Womack’s road manager brother threw his guitar out of the bus window while he was asleep.” Later, his fame achieved, Hendrix makes an awkward visit to his old high school in Seattle. A kid asks him how long ago he left: “Oh, about 2,000 years.”

Hendrix carried sadness with him all of his short life, a kind of emotional dispossession for which he compensated with sartorial flamboyance, huge amounts of sex, a keen interest in UFOs, etc. It also poured through his guitar, of course. And a sadness sets in as one reads the last two chapters of Wild Thing. It’s the sensation of Hendrix slipping out of the story, out of this world, out of the hands of another biographer. Jimi Hendrix passed into oblivion in September 18, 1970 in a London flat, unattended, having taken 18 times the recommended dose of a German sleeping pill called Vesparax. Leon, whose life had become a kind of shadow version of his older brother’s, got the news in jail, jail-style: He was “waiting to start his shift in the kitchens, when a fellow inmate shouted to him that his brother was dead.”

Could Hendrix have been saved? Possibly. Did he want to be saved? Who knows. His friend Eric Burdon, of the Animals, thought not: “He died happily and he used the drug to phase himself out of existence.” But Chandler, the man who four years earlier had brought Hendrix to England, would not countenance the idea of self-destruction: “Out of the question.” For us, 50 years on, Hendrix seems simply to have vanished, oh so wastefully, into the maw of a ’60s-flavored contingency, his evanescent personality finally dissolved in a random suspension of pills, carelessness, appetite, desolation. What he left us with, meanwhile, can never die.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.