In continuation of TPR's ongoing coverage of state legislative efforts to wrest planning and zoning control from local governments, republished here with permission is the Embarcadero Institute’s plain-language analysis of state housing data, which fails to support the foundational premise of SB50 that increasing housing supply will result in housing affordability. Find Embarcadero Institute’s original report and more resources on local policy impacts of state legislative proposals here.

Gab Layton

"In contrast to claims from some media and academics, state data (from the Department of Housing and Community Development 5th cycle Annual Progress Report) confirms that most of California’s transit-rich urban counties are not resisting housing density."

1. California's Soaring Transit Expenditures are Failing. Why?

About 90 percent of California’s transit is located in 13 counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Marin, Orange, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, Sonoma and Ventura. These 13 counties are home to some of the most densely populated Urbanized Areas (UAZs) in the nation. Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, San Francisco-Oakland and San Jose, for example, are all more densely populated than New York-Newark.

Our legislature favors transit-oriented development (TOD) as the greenest way to house our next generation of Californians, and as a result these 13 counties are the focus of numerous state housing bills. 1. California's Soaring Transit Expenditures are Failing. Why?

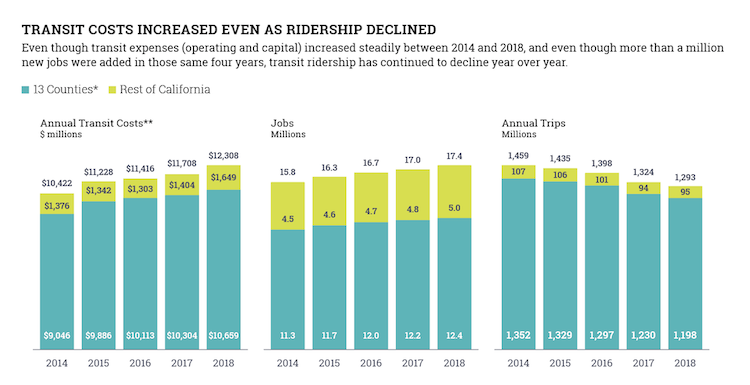

Yet we see a growing mismatch between policy and outcome. While transit costs continue to soar (costs increased by a dramatic 20% over the last 4 years), transit use is in decline. California performs poorly against national benchmarks for transit use.

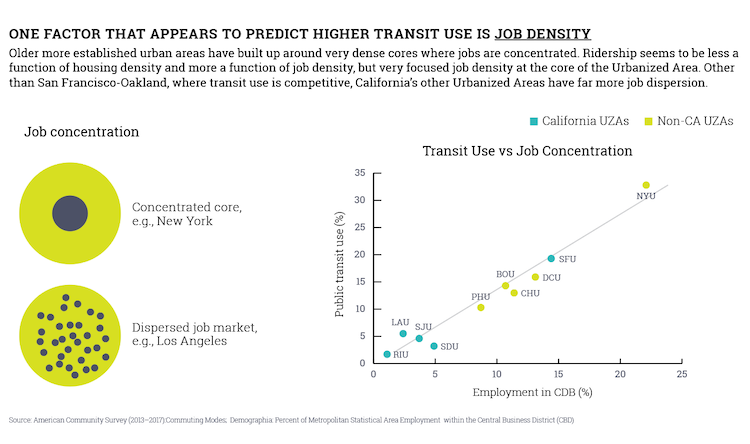

We find a mix of reasons for this. First, California’s transit is largely bus-centric, and buses are trapped in the same traffic as cars. Second, jobs in California are highly dispersed. Transit works best with job density. Commuters are more likely to take transit if they can walk to jobs from transit stops, not if they can walk to transit from their homes. Co-locating jobs can focus commute patterns, creating greater scale and enabling more efficient transit with greater frequency.

States with higher transit use do two things differently from California: their transit is centered on rail, and they concentrate jobs near rail stops.

For more detail on California’s transit mismatch, visit our latest transit report.

2. Most Transit-Rich Urban Counties are on Target to Hit or Soar Past State-Required Housing Approvals by 2025. But These Results are Achieved by Approving Luxury Housing at the Expense of Affordable Housing

In contrast to claims from some media and academics, state data (from the Department of Housing and Community Development 5th cycle Annual Progress Report) confirms that most of California’s transit-rich urban counties are not resisting housing density.

In fact, by 2025, these counties will easily surpass their state-required housing approvals, known as Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA): Alameda, Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Marin, Orange, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano and Sonoma.

What is broken? Has the state set the housing targets too low? Are “density bonuses” (incentives for developers to include a percentage of affordable housing in their projects) set to trigger too low? If the state has set low-income housing quotas at around 40%, but density bonuses trigger at 10%, that leaves cities and counties with the hurdle of subsidizing the remaining 30%. But cities and counties are not allowed to raise funds for affordable housing, and the state redevelopment agencies that previously helped with the financing of affordable housing were shuttered in 2012. Is it surprising then that cities and counties cannot reach their low-income housing targets?

This is a key policy issue for decision-makers: rezoning won't create affordable housing. Affordable housing needs subsidy.

Of the 25 counties falling far behind their housing targets, 20 are largely underpopulated and rural. Sacramento, Riverside and Kern distinguish themselves on this list because they are large and populous, but Riverside and Kern do not have the same transit investment as most of the other urban counties.

If there is a takeaway from the state data it is that urban counties with strong transit generally are having no trouble approving market-rate housing. The controversial Senate Bill 50 (Wiener) was focused on stimulating market-rate housing in transit-rich municipalities, but that does not seem to be the problem. The problem is transit-poor counties can’t reach their market-rate housing targets, and every county needs help with low-income.

The very real problem of subsidizing affordable housing was addressed in Senate Bill 5 (Beall, McGuire, Portantino), which enabled counties to redirect some of their property taxes to subsidize qualified affordable housing projects. Although the bill was passed by both houses in 2019, in the end it was vetoed by Governor Newsom.

Senators Beall, McGuire and Portantino are making a second attempt to address the subsidy issue with SB 795 — Affordable Housing and Community Development Investment Program. This bill, again, attempts to claw back some funding for cities and counties so they can invest in affordable housing. Right now, all income tax goes to the state, and most property tax is assigned to education. Cities are caught in an impossible situation - the state has made them accountable for building affordable housing but the state holds the purse strings, as we found in this in-depth sampling of Bay Area cities.

Separately, more work needs to be done to understand why Sacramento, Riverside and Kern counties are so far behind in their housing goals. Might inadequate transit have played a role for Riverside and Kern? It is important to understand the locale-specific challenges before passing legislation that fixes the wrong problem and sweeps in regions who are not behind.

3. The State Must Be Transparent Regarding Which Housing Target It Believes

Finally, going forward the state needs to resolve inconsistencies in its generated housing targets. HCD (California's Department of Housing and Community Development), in its report California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities (2015) claims that 180,000 units should be approved statewide per year. Yet HCD's formal RHNA target is closer to 140,000 per year. What is behind this discrepancy?

Click here for RHNA targets vs. RHNA achievements, by county.

In addition to that confusion, policymakers are citing, instead of the state's own HCD data, a McKinsey & Company report that wrongly stated California needed 3.5 M housing units by 2025 - a number McKinsey achieved by using the State of New York as California's benchmark. New York's demographics, average household size and key housing data are dramatically dissimilar to California and render New York unusable as a benchmark for California.

So, the state has muddied the waters by citing three possible housing targets:

- The erroneous 3.5M units said to be needed by 2025 which is not based on California demographics and which would have California adding 600,000 homes a year. That’s more than half the supply added by the entirety of the nation annually, yet California represents only 10% of U.S. population and almost half of the 50 states are growing faster than California.

- The state-mandated Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) developed by California’s Department of Housing and Community Development. These allocations are based on California demographic projections and take into account rates of household formation, household size and income, vacancy rates and jobs. Housing need is allocated by city and is applied in a 5-year or 8-year cycle. When these targets are annualized, they require about 140,000 homes per year, 60,000 of which are supposed to be affordable (very low or low-income).

- The same Department of Housing and Community Development's 10-year forecast in California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities (2015) which has the target number at 180,000 homes per year until 2025.

The state needs to clarify which housing numbers it will enforce. If the state decides to reject its own RHNA numbers, it should transparently inform the public and policymakers of its reasoning. And since the state requires cities to annually report their progress on housing approvals, the data and emerging trends should be made transparent to policymakers and the public before the drafting of legislation.

It is clear from that RHNA data that while all 58 counties struggle to reach affordable housing targets, the challenge to build market-rate housing is locale-specific and not statewide. SB-50 targeted transit-rich urban counties, but those counties, on the whole, will hit their housing approval goals or go far beyond without changes in state law. The state should instead investigate challenges faced by the obvious outliers among the most populous counties — Sacramento, Riverside and Kern — to discover the locale-specific challenges they face in approving housing.

- Log in to post comments