Google’s Guinea-Pig City

Will Toronto turn its residents into Alphabet’s experiment? The answer has implications for cities everywhere.

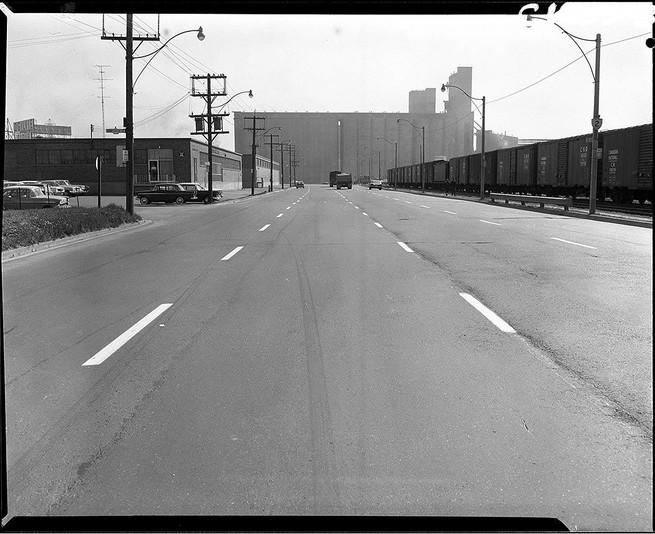

Quayside is a nondescript, 12-acre chunk of land on the southern edge of Toronto’s downtown. It’s just three miles from my apartment, but getting there takes almost an hour by subway, bus, and foot. When I finally arrive at 333 Lake Shore Boulevard East on a windy day in early January, I find a vacant parking lot full of snow. The abandoned Victory Soya Mills silos loom at its edge—a remnant of the city’s industrial heyday. The plot is half of the future site of Sidewalk Toronto, a “neighborhood built from the internet up” by Google’s sister company, Sidewalk Labs. Lake Ontario is frozen and it’s colder than the surface of Mars the day I go to look at the site.

It’s a far cry from the vision that fills the Sidewalk Toronto webpage, where a crisp video shot on a sunny day makes the Victory silos look cheerful and full of potential. Torontonians in puffer vests and toques describe a vibrant city bursting at the seams. Toronto’s population grew by 4.5 percent between 2011 and 2016. The city tolerates a high cost of living and a low rental-vacancy rate.

According to Dan Doctoroff, Sidewalk Labs’ CEO, these “incredible challenges of growth” can be surmounted with the right application of innovative technology. But Sidewalk Labs’ offer doesn’t come with guarantees or without strings. For locals, an obvious question arises: What’s in it for Toronto?

Sidewalk Labs is the realization of Google’s long-standing dream to “give us a city and put us in charge,” as the former Alphabet executive chairman Eric Schmidt once put it. As Alphabet’s smart-cities division, the company works to “accelerate urban innovation” through technology deployments undertaken in collaboration with cities. Before establishing Sidewalk with Google CEO Larry Page, Doctoroff had served as the deputy mayor for economic development under New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg. He led New York’s two unsuccessful Olympic bids, then catalyzed those efforts into PlaNYC, a large environmental and economic redevelopment plan.

As Sidewalk’s first public project, one of its portfolio companies replaced phone booths in New York with kiosks for browsing the internet and charging phones. The effort sparked concerns over data mining and privacy. In October 2017, it announced its most ambitious project yet: transforming the underdeveloped Toronto waterfront into an affordable, eco-friendly smart neighborhood—a little model town to showcase Sidewalk’s innovative technologies and urbanist ideas. For the privilege, Sidewalk has committed $50 million to a year-long, joint-planning process with Waterfront Toronto, an urban-development corporation.

As with Sidewalk’s kiosks, privacy activists have expressed concern about the sensor systems Sidewalk proposes to run their smart city. But other concerns are economic. It’s common for American companies to attempt big Canadian expansions, which often end poorly. In 2013, for example, Target attempted an ambitious cross-border expansion after acquiring the leases held by a Canadian discount chain, Zellers. It collapsed two years later, leaving behind dead malls and a gaping hole in the Canadian retail market.

Even when such efforts succeed, they Americanize huge swathes of the Canadian economic landscape, draining capital and talent from Canada. This occurred most notably in the 2006 acquisition of the Hudson’s Bay Company by the American financier Jerry Zucker. The Hudson’s Bay Company, which drove the development and colonization of English Canada beginning in 1670, was handed off to a New York private-equity firm, who began a campaign of subsidiary closures, layoffs, and rebranding in 2011. It was this downsizing of the HBC-owned Zellers chain that paved the way for Target’s ill-fated run.

Concerns about the economic stability of the project are reasonable, given that Sidewalk’s plans are hypothetical. Other recent smart-city attempts, like the Bill Gates–connected Belmont, Arizona, project, have chosen unincorporated greenfield locations for maximum freedom—and to avoid extended politicking about logistics and market disruption. But Sidewalk prefers to work with existing cities, harnessing their infrastructure and populations without the costs and risks of building their own. If successful, the results could offer significant benefits to Sidewalk and Alphabet. Doctoroff sometimes talks like Jane Jacobs, but as he told The Verge last year, “We’re in this business to make money.”

Quayside—pronounced KEY-side—is part of Toronto’s Eastern Waterfront. Formerly dominated by industry and shipping, it’s now comprised mostly of brownfields prone to flooding from the lake and the Don River. For decades, revitalization projects have been proposed for the area, each promising to unlock Toronto’s potential as a “world-class city.” Some have been successful, including a restoration of Sugar Beach and a housing and infrastructure effort built for the 2015 Pan American Games. Others have been slow-moving disasters, like the Gardiner Expressway, a multigenerational boondoggle that many Torontonians think should be dynamited or buried.

Waterfront Toronto, the urban-development corporation that owns the majority of the Quayside site, is the most recent organization to take on the challenge. Publicly funded by the Canadian federal government, Ontario’s provincial government, and the city of Toronto, its governing board is appointed, not elected, and composed predominantly of wealthy individuals—many of whom are involved in real-estate development. Since 2001, its mission has been to revitalize the area around the Toronto harbor through development, environmental remediation, public-transit expansion, and site-specific public projects. Having expended 1.5 billion Canadian dollars in seed funding, Waterfront needs a new partner with deep pockets to continue its mission. That makes Sidewalk’s $50 million commitment (about 63 million Canadian dollars) all the more attractive.

In March 2017, a request for proposals sought an “innovation and funding partner” to help Waterfront Toronto take on Quayside. The goal: to transform the area into a “highly sustainable mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhood” that would create jobs and provide affordable housing in a city where one-bedroom condos in the downtown core routinely sell for 500,000 Canadian dollars.

Waterfront wouldn’t tell me much about the selection process, although they did confirm that some local and Canadian firms submitted proposals. Sidewalk Labs went further. It submitted a 200-page response, including a “project vision” laying out a “new type of place” in tempting detail: Modular, dynamic buildings that could be adapted to new uses throughout the day; subterranean utility channels filled with robots whisking away garbage; and outdoor spaces designed to minimize the impacts of bad weather. Sidewalk Toronto would be affordable and entrepreneurial, incubating start-ups from Sidewalk’s portfolio, Canada, and around the world. The proposal envisions a vibrant collection of neighborhoods spreading over the entire Eastern Waterfront, devoted to arts, commerce, and urban innovation—including Google’s Canadian headquarters and an “urban innovation institute” as anchor tenants.

Upon the announcement of the agreement, Toronto Mayor John Tory enthusiastically endorsed the vision, saying, “By having Sidewalk interested in coming here, we’re building up our credentials as the place to be in the world.”

But the terms of the deal aren’t clear. What the public does know is contained in a four-page summary. The agreement entails a year-long “initial joint planning process,” during which Sidewalk and Waterfront will develop a Master Innovation and Development Plan for Quayside. This will need to be approved by the boards of Sidewalk and Waterfront and ultimately the relevant government authorities. At the end of the planning year, either Sidewalk or Waterfront could walk away. Sidewalk will commit $10 million to fund the planning process; an additional $40 million in payments will be triggered as Waterfront meets certain conditions, including the beginning of a massive flood-protection plan necessary before any development can take place—let alone the on-site installation of sensors, cameras, and other smart objects for the urban future. Sidewalk stands to benefit from 1.25 billion Canadian dollars in environmental spending committed by the city, the province, and the federal government to remediate the floodplain.

Still, Toronto might enjoy tangible benefits under the terms of the agreement. Among them, Sidewalk has offered to “facilitate” a commitment from Alphabet to bring Google’s Canadian headquarters to the site as an anchor tenant. Sidewalk Labs’ representatives clarify that this involves “helping Google Canada find appropriate space” on the Eastern Waterfront. What this commitment means in terms of jobs and economic impact is unclear. In 2016, Google opened a new engineering headquarters in Kitchener-Waterloo, where Canada’s top engineering school is located. At 185,000 square feet, it’s more than a third the size of the entire Quayside site. Google’s existing Toronto office consists of five floors on Richmond Street and mostly handles sales, advertising, and business accounts. Google confirms that the current plan is to move the Richmond Street offices—around 300 employees out of Alphabet’s 75,000 globally—to the site, with little expansion for the time being. This move would be attractive to Waterfront, as it would move a large office to a part of the area that can feel deserted. But when compared to the promise, the impact seems limited, at least for now.

The framework agreement also calls for an “Urban Innovation Institute” at Quayside. Sidewalk’s vision document seems to see it as a quasi-academic organization, “a place for collaboration and discussion, and an unprecedented opportunity for faculty and students to test their ideas in a real urban environment.” But it doesn’t talk about partnering with any of Toronto’s many universities and colleges. It’s unclear whether this would be an academic research unit subject to an academic ethics review board, or a private resource where researchers would work on Sidewalk’s technology portfolio. Sidewalk’s spokesperson told me the matter had not been settled.

Micah Lasher, a former New York City official in Michael Bloomberg’s administration and the current head of policy and communications at Sidewalk, strongly emphasized the ongoing nature of the planning and consultation process. “I would be circumspect about placing too much weight on any given idea in that [vision] document, because any given idea might not make its way into the final plan,” he told me. “We’re talking with lots of folks.”

To facilitate those interactions, a public-engagement plan offers many ways Torontonians can engage. They include live-streamed talks, public roundtables, Sidewalk Toronto “pop-up stations,” a “design jam” with architects and planners, and a two-day CivicLabs workshop on “issues like mobility, housing, and inclusion.” Interested citizens can also send their children to a free “Sidewalk Toronto Summer Kids Camp.”

Even so, it’s unclear how much of an impact ordinary Torontonians will be able to have on the project through these outreach mechanisms, many of which sound more like marketing efforts than public meetings. According to the plan’s timeline, most of the initiatives won’t get off the ground until March or later anyway. And the power struggle over who gets to decide the future of the largest city in Canada is just beginning.

Sidewalk has made it clear that its interests extend beyond Quayside; it has designs on the entire Eastern Waterfront, which totals over 800 acres—an area as wide as the island of Manhattan and almost as big as Toronto’s downtown core.

The company’s lengthy response to the RFP outlines a massive urban undertaking, with Sidewalk’s portfolio of companies and technologies making up its infrastructural core. The vision document emphasizes that Sidewalk’s technology—its carbon-negative energy solutions, affordable housing, and autonomous-vehicle playground—can only operate efficiently at the scale the entire Eastern Waterfront provides. Without the Eastern Waterfront, much of Sidewalk’s smart-city dreams become unrealistic.

If the Sidewalk Toronto project were implemented as described in the vision document, the area would become some of the most heavily surveilled real estate on the planet. Sidewalk describes neighborhoods “over-provisioned” with “a broad range of sensors” to “enable parallel experimentation with multiple technology approaches.” Data from these sensors would be stored and processed to feed controls for everything from the ambient temperature of buildings to crosswalk signals to the assigned uses of adaptable private and public spaces. As the Eastern Waterfront is optimized to Sidewalk’s standards, whatever those are, the tech underlying also benefits, primed for redeployment in other locales.

When I asked about data gathering, Lasher responded, “We’re not going to gather up all Torontonians’ data and sell it, we’re not building Sensorville.” But in this case, the sale of resident data might be of less concern than its use. Residents and visitors to the Sidewalk site would provide valuable benefit to Sidewalk, allowing their daily lives to help optimize technology for Sidewalk’s broader commercial venture. Harvesting data from citizens, including children and those in need of affordable housing, is an aspect of the Sidewalk Toronto project that deserves careful thought.

If “ubiquitous sensing” (Sidewalk’s term) is a goal within the Sidewalk Toronto neighborhood, its effects are already being felt in the rest of Toronto. Doctoroff is talking about launching tech pilots “right now” in different locations around the city, beyond Quayside. These pilot projects would let Sidewalk show off its tech and drum up enthusiasm over a long planning cycle. They might also normalize the experience of being a free-range experimental population within the city. If Toronto residents become accustomed to encountering Sidewalk pilots all over town, they might be less leery of the built-out neighborhood if it arrives.

The Sidewalk Toronto vision document is extremely detailed—dazzlingly so for a parcel of land Sidewalk doesn’t even really have permission to think about yet. It’s a clever move. Most of the media coverage of the deal has parroted Sidewalk’s claim to the entire Eastern Waterfront. The tech press covered Google’s 800-plus acres of autonomous cars and modular buildings as if the groundbreaking was imminent. But according to Waterfront, the signed deal doesn’t even include development rights for Quayside, let alone the entire parcel. Sidewalk has defined the terms of the conversation, placing government and critics in the position of responding to Sidewalk’s techno-utopian picture book, and casting themselves as enemies of innovation if they dispute it.

The power of storytelling is nothing new to Doctoroff. In Greater Than Ever, his new book on his time in the Bloomberg administration, Doctoroff talks at length about preparing detailed, emotionally affecting presentations to sell city officials and private funders on the idea of a New York Olympic bid in 1996. Doctoroff’s presentation invoked West Side Story, Lincoln Center, Central Park, and the Statue of Liberty to convince his audience that “hosting the Olympics could spur New York’s next big leap forward.” Sidewalk’s vision document plucks on similar urban heartstrings, anchoring itself with hand-drawn illustrations of hyper-local Torontonian landmarks and icons. Sidewalk Labs plays on Toronto’s anxiety about its standing and future to argue that Sidewalk is the “jump start” needed for Toronto to be a “dynamic city stepping ahead.”

In his book, Doctoroff explains how the 1996 presentation deliberately offered extreme detail and emotional appeal to try to close the deal. The Sidewalk vision document follows the same rhetorical model. Not only will the Loft buildings be readily convertible to different uses, but they will also be insulated with mycelium! Not only will trash be swept away by autonomous robots, but here’s a cute drawing of them! By laying out a vision of the future in such detail, with such charm and techy charisma, Doctoroff and Sidewalk are narrowing the scope of conversation.

When I press him on the matter, Micah Lasher downplays the concern. He calls the 200-page proposal “a snapshot in time of some ideas and values.” He cautions that “many of those ideas may be discarded” during the next nine months of consultation and planning.

But Waterfront Toronto representatives have identified, in interviews and at public events, the scope, depth, and detail of the Sidewalk response to the RFP as key to their winning the deal. As one Waterfront official described it to me, “Sidewalk, at the end of the day, put together the infrastructure, the technology, the thinking, the funding, and the real estate. They were able to pull the whole thing together. And that’s why they came out on top.”

Perhaps it’s more useful to review the vision document less as a promise, and more as a statement of Sidewalk’s urbanist ideology. It offers a blueprint for Alphabet’s idea of a city, whether in Toronto or elsewhere.

Take real estate, for example. The document emphasizes affordable housing and a diversity of planned neighborhoods. But the reconfigurable buildings Sidewalk proposes are structured in a way that seems to preclude long-term, individual ownership of an apartment or a storefront. Residential and commercial spaces appear to be designed for brief, transitional tenancies, built for “ongoing and frequent interior changes around a strong skeletal structure.”

One-bedroom micro-apartments, ranging from 540 square feet to a claustrophobic 162 square feet, feature heavily in Sidewalk’s “affordable housing” solution, along with “innovative financing structures” like collectives and communitarian housing. A page of the vision document is devoted to these tiny dwellings, complete with sample floor plans. Mt. Carmel Place, a micro-housing development in New York, is cited as precedent. There units ranged from 260 to 360 square feet, renting at market rates of $2,446 to $3,195. “Affordable” units went for $914 to $1,873.

Are these workable solutions for the “families” the document constantly invokes as Sidewalk Toronto residents? Homeownership is important for the stability of communities, and it is a core component of intergenerational wealth building. Would collective ownership enable that? Likewise, Sidewalk’s emphasis on pop-up shops, fast-cycling start-ups, and next-gen bazaars doesn’t seem to balance innovation with the routine needs of a livable neighborhood. Sidewalk likes to invoke Jane Jacobs, for whom Toronto was an adopted home, when talking about the benefits of flexible zoning. But Jacobs also emphasized the need to avoid fast turnover in businesses and residences, so that stable neighborhoods could develop. The social functions served by a grocery store or a coffee shop can be more valuable than the services they provide, even if they’re not the most innovative or profitable.

When asked whether this apparent design-for-turnover would impact the stability and organic growth of the neighborhood, a Sidewalk spokesperson responded, “Enabling change does not mean forcing change.” On the matter of resident homeownership, they deferred to the ongoing effort, saying, “The specifics of how we achieve a socioeconomically diverse mix of housing [are] going to be figured out as part of the planning process.”

Sidewalk also wants to use the Toronto project as an open acquisitions incubator, growing start-ups it can add to its portfolio of companies or pass on to the “marquee North American VCs” it intends to attract to the project. A Sidewalk spokesperson indicated that the company hoped to attract a diverse pool of investors to the neighborhood from around the world. Importing Sand Hill Road venture dollars might seem like a boon for the city, but the influx of cash has the potential to warp the Toronto tech economy, furthering income disparities and exacerbating the existing real-estate crisis.

If successful, Canadian companies and their founders are also likely to get relocated to the United States, where the dreams are brighter and the paychecks are bigger. The influx of Canadian entrepreneurs, designers, and developers may not seem significant from an American perspective, but their departure can have substantial impacts on local Canadian economies in terms of jobs lost and companies shuttered or never started. One example is the 2015 closure of the premiere Canadian interaction-design firm Teehan and Lax. After its principles were acqui-hired by Facebook, about 40 designers, developers and other creative staff were laid off.

Sidewalk also seems to want to sidestep existing land-use policies to accomplish its goals. It says “outmoded regulations” hold cities back from achieving their full innovative potential. In order for Sidewalk’s “climate-positive,” “adaptable” buildings to be deployed at a large enough scale to be cost-efficient, “a new paradigm in the building code” will be required. Likewise, innovations in transport and energy production “may require substantial forbearances from existing laws and regulations.” Sidewalk advocates “outcome-based” building and zoning codes, a style of regulating construction and development that relies on modeling and real-time monitoring to allow “flexible buildings” to be used for a broad range of uses in real time.

Prescriptive zoning, Lasher insists, “reduces vibrancy of use and it makes it hard for neighborhoods to adapt over time.” When I ask about specific ordinances and regulations that could be replaced with real-time-monitoring-enabled, outcome-based codes, he cites legal dispensations for autonomous cars and zoning forbearances that would allow light manufacturing (such as woodworking studios) to be placed in residential areas. But ultimately, Lasher insists that the matter will be resolved in collaboration with city policy makers.

Sidewalk is careful to say that the wealth of detail in its vision document is speculative, an example of how things could go on the Eastern Waterfront. It seems that the only thing they know for sure is that Sidewalk Toronto can’t be built to its fullest innovative potential under current methods of city management. By asking preemptively for regulatory dispensation, Sidewalk is making clear that the Toronto city government may not know enough to regulate its own fate, at least not right now. Sidewalk’s “city of the future” might best be compared to a special economic zone, an area of regulatory exemption that allows it to innovate to its heart’s content, beyond the normal laws of its host municipality.

Denzil minnan-wong, a Toronto deputy mayor, has strongly criticized the organization’s handling of the deal, saying it’s lacked transparency and meaningful consultation. He is the only member of the city council who also sits on the Waterfront board, and thus the only member who has seen the agreement between Waterfront and Sidewalk. In December 2017, the Toronto city council approved its own planning framework for the Eastern Waterfront, unrelated to Sidewalk Toronto, which instead focused on expanding film production and studio space to support the Toronto film industry. A city councilor said Sidewalk had overstepped their bounds. And in a Toronto city council executive committee meeting in late January 2018, a visibly frustrated Minnan-Wong argued for the release of the agreement text to the council, saying, “I know enough about the agreement that I think you would like to know more about the agreement.”

Waterfront and Sidewalk have been closed-lipped about what this means for their mutual aspirations. Micah Lasher says that Quayside is still a “historic opportunity.” But he also claims that the site is just a “pilot.” Is Sidewalk biding its time, waiting for Toronto to come around to its way of thinking over the coming year of presentations, discussion groups, and summer camps?

The company denigrates planned communities, which they say “address needs that are already out of date by the time construction is complete.” But Sidewalk Toronto would be a planned community. It might not be Levittown, but the envisioned technological interventions direct some lines of thinking and foreclose others. Perhaps Sidewalk doesn’t dislike planned communities so much as other people planning them.

Its vision of what a city should be appears to be an entity under Sidewalk’s wing, bursting with potential that Sidewalk can properly channel if granted the freedom it deserves. In this model, cities, people, infrastructure, and culture become resources for reincorporation into Alphabet’s corporate aspirations. The company appears to justify that claim on the grounds that American venture capital, the opportunity to play with the latest tech, and the chance to win Google jobs is worth trading for the keys to the city.

But back at 333 Lake Shore Boulevard East, where it’s colder than Mars, the current reality doesn’t seem so appealing either. There’s nothing here now, and some would argue that any development here would be an improvement. If Google and Sidewalk want to dump $50 million on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, why kick up a fuss?

Instead of asking if this specific plan has promise, it might be better to pose more general questions: Who are cities for, and who gets to decide how they grow? Sidewalk Labs hopes the answer is technology companies. But the city still has a shot at responding to this assumption. The answer might have implications well beyond Toronto—eventually, it might impact cities everywhere.