Frank Lloyd Wright's Striking Pop-Cultural Legacy

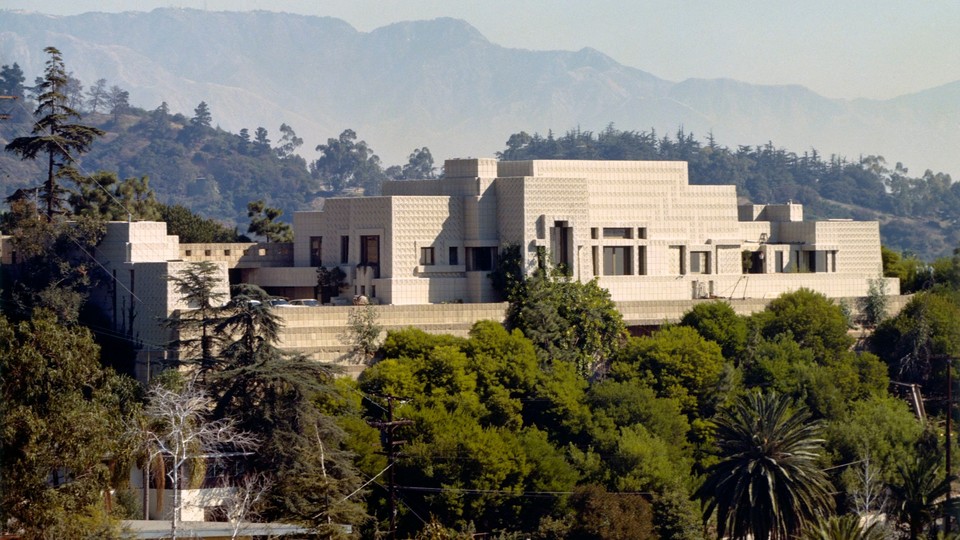

150 years after the architect was born, the Ennis House is a testament to his continued influence—particularly onscreen.

The apartment of Rick Deckard in Blade Runner. The titular House on Haunted Hill, where Vincent Price’s character invites guests to survive a night of frights and win a fortune. The penthouse setting of Twin Peaks’s faux soap opera “Invitation to Love.” The Great Pyramid of Meereen, prominently featured on Season 6 of Game of Thrones.

These TV and film settings span decades and genres, from science fiction to horror to fantasy. But they have one crucial connection: They all either filmed in, or were directly inspired by, one private residence in Los Angeles: the Ennis House, built in 1924 by Frank Lloyd Wright. Stone-colored and covered with intricately patterned tiles, it looms imperiously from atop the Los Feliz hills—and, as the Historic American Buildings Survey described it in 1969, “appears from the distance as a tremendously large monument rather than a two-bedroom dwelling.”

Wright, who was born 150 years ago this year, may have gone too far with the Ennis House; it’s a dramatic, not particularly inhabitable example of how far he would go in his experiments toward developing regional styles. But as a paean to striking grandeur, it has had a beguiling effect on its viewers. And it’s a remarkable example of why, nearly six decades after his passing, Wright is still considered the preeminent American architect, who has been described as “a mass of contradictions” but also as “a maker and mirror of the American century.” The Ennis House is a mostly unconsidered piece of that legacy, but incorporated into pop culture again and again it serves as a peculiar and living testament to Wright’s unique contributions to the visual landscape—in real life and onscreen.

On the cusp of building the Ennis House, Wright was in an unusual place professionally. The architect’s career was seemingly secure. He had made a name for himself in Chicago, winning important contracts and making bold statements, like Unity Temple in Oak Park. But large-scale success eluded him. By the early 1920s, Wright was returning from a multi-year stay in Japan and hoping to establish an office in Los Angeles. He was already using the practices he’s best known for, now referred to as “organic architecture”: the blending of indoor and outdoor, transitions between rooms bursting from small spaces to vast halls, modular building elements, unique patterns for each project that integrated ornamentation into construction, and the use of local materials and colors.

At this point, it was almost a decade before Wright would build Fallingwater—the private residence in the western Pennsylvania woods dramatically cantilevered over a waterfall that would finally put him on the cover of Time and permanently in the national spotlight. To his great frustration, Wright wasn’t being offered the most prominent projects available. To remedy this, and because he saw an immense opportunity, he began creating houses in Southern California with his son, Lloyd Wright, and Rudolph Schindler, an Austrian architect. Refining his ideas with each project, Wright sought to create a regional style, taking into account everything from LA’s weather to the latest architectural trends and techniques.

Los Angeles was attractive to Wright for several reasons. The city’s rapid expansion presented a chance for the architect to indulge a growing interest in urban planning. Both Wright and his son had contacts in LA’s film industry, and he hoped to leverage them into new work. According to Merrill Schleier, a professor emerita of art and architectural history and film studies at the University of the Pacific, Wright corresponded with the directors Cecil B. DeMille and Preston Sturges, as well as actors like Charles Laughton. Wright had already explored blending interior and exterior spaces, too—his compound in Wisconsin, Taliesin, was built into a hillside, seamlessly incorporating a loggia and gardens—and sunny California seemed like a natural venue to experiment further with outdoor living.

Wright looked south for inspiration, too. Mayans and other pre-Columbian societies built intricately carved stone structures and enormous, stepped-back pyramids. They also had a rich ornamentation featuring jungle animals and gods. In the 1920s, as Art Deco began to take off, copying Mayan designs was becoming popular with American architects. Wright wanted to incorporate some of those elements in a way that would emphasize LA’s topography and climate, and that was affordable and replicable throughout the region.

The architect thought that an experimental construction technique with concrete—already a relatively common building material, and available in do-it-yourself form for use at home—might be the key. He didn’t particularly like concrete, writing in his autobiography that it was “the cheapest (and ugliest) thing in the building world.” But he did understand the material’s potential and challenged himself to make it beautiful, posing the hypothetical, “Why not see what could be done with that gutter-rat?”

For his new LA projects, Wright developed a system to mold the concrete with metal and knit it around a steel lattice—literally making it into a textile—at the construction site. The blocks were 16-inches square and about four inches deep. They were faced with a Mayan-influenced geometric pattern, and buff-colored, like sandstone. In each of his California houses, from Hollyhock to La Miniatura to Storer to Samuel Freeman, Wright refined the technique. But the first time Wright used the blocks to full effect was in the Ennis House.

In Blade Runner, Rick Deckard, played by Harrison Ford, returns to his apartment, which is clad in Ennis-style textile blocks. The interior set was created by production designers who made a foam mold of the Ennis blocks, then built the walls and ceiling of Deckard’s cramped and dark apartment using the dummy blocks. The effect is impersonal, near-alienating; it’s the perfect futuristic interpretation of a Chandlerian noir detective’s office. (The only footage actually shot on location at the Ennis House is an exterior shot that sees Ford wrapped in a blanket, staring out at a sci-fi Los Angeles, circa 2019.)

Wright’s bold vision may have worked well for Blade Runner, but ultimately Ennis fails at its primary real-life function: being a home. It’s just not suited to everyday living. The house’s unusual windows, inset between rows of blocks, diffuse the bright California light and accentuate the interior’s eerie quality. Some ceilings are as high as 13 feet, making for rooms that can feel cavernous.

Kenneth Breisch, an architecture professor at the University of Southern California, says Ennis is in line with Wright’s other textile-block homes in LA, including the Samuel Freeman House (which Breich is responsible for the restoration of). “I’ve spent a lot of time up there with students,” he notes of Freeman. “It’s cold and damp in the winter. It’s not well heated. And it’s hot in the summer. They’re not very comfortable houses, really, in the end. You’re living in a concrete box, basically.”

According to Schleier, even Wright, an architect who unabashedly iterated on the same idea from project to project, acknowledged that he might have missed the mark with Ennis, saying in a 1954 oral history:

I built the Storer house up on a hill—it’s a little palace. It looks like a little Venetian palazzo. Then I built the Freeman house, and then there was finally the Ennis house, which was way out of concrete-block size. I think that was carrying it too far—that’s what you do, you know, after you get going, and get going so far, that you get out of bounds. And I think the Ennis house was out of bounds for a concrete-block house.

It’s hard to know exactly what Wright meant by “out of bounds.” For living in? For widespread public adoption? But decades later, a way in which Ennis was definitely in bounds was as a dynamic set for film and television. In Blade Runner, the house—and the facsimile version of it built for interior shots—is an ideal fit. It feels both futuristic and like it’s from an ancient civilization, a sensibility that Schleier, at the University of the Pacific, calls “archeological.” The geometric patterns on the textile blocks could be seen as Central American, or as reminiscent of circuitry. The blocks look both earth-wrought and machine-made, which they are. Through its specificity, the Ennis House has acted as a pop-cultural cipher: It blends into the multiracial future depicted in Blade Runner and as a lair for the undead in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

In Buffy, the house serves as the Crawford Street Mansion, ostensibly an unoccupied Southern Californian mansion, which isn’t too much of a stretch. But in the Buffyverse, the house is a headquarters and hideout for vampires (first Angelus, and then Spike and Drusilla). As in Blade Runner, the production designers created a faux interior that would match the exterior of Ennis House. Logically, it’s another great match—from the outside, Ennis looks like a place that doesn’t get a lot of vampire-disintegrating sunlight.

A production that uses the actual interior of the Ennis House to great effect is Twin Peaks, in its original two seasons. A cult masterpiece famous for its weirdness and ambience, Twin Peaks mostly takes place in the foggy darkness of the Pacific Northwest. The series’s interiors, as in the Great Northern Hotel, are typically timber, rugs, and antlers. For the show within a show, the cheeky soap opera called “Invitation to Love,” the director David Lynch and his crew chose to shoot on location at the Ennis House. The mansion’s concrete-clad rooms provide a useful contrast to help differentiate between the two settings, with Ennis serving as a splendidly Lynchian backdrop: creepy but credible.

Other factors contributed to the Ennis House appearing onscreen a lot. Proximity to Hollywood didn’t hurt, and later, the nonprofit responsible for the house at times needed to raise revenue. An earthquake in 1994 caused damage, but according to Breisch, “the textile blocks have always been a problem. They tended to erode.” Augustus Brown, the owner of Ennis throughout the ’60s and ’70s, made things worse by applying an epoxy to many of the concrete blocks that locked in moisture and exacerbated their deterioration.

In 2011, Ennis was bought by the billionaire Ron Burkle. Terms of the sale prescribe the rehabilitation of the building, and at least 12 days of public access each year. Burkle’s plans for the house, including its future use as a set, are unknown.

Regardless of the countless times the Ennis House has been immortalized on film, Wright’s textile-block structures were not the big break the architect was looking for. Hollywood contacts were not enough. Wright headed back east and would not build in California again for years. He would briefly go into bankruptcy the year after Ennis, taking him into the difficult years of the Great Depression.

Even before that period, as he was working on Ennis, Wright found his personal life in tumult, thrown into darkness: In short order, his mother died, he married his partner, and then they separated because of her morphine addiction—all before he finished Ennis. It’s possible that these events influenced the way the house was built. Breisch points out the stark difference between the plans for Ennis and those for Doheny Ranch, an ultimately unbuilt Southern California suburban development. Of the latter, he says, “It’s just shortly before [Ennis], but before a lot of the problems that he had. It’s still sort of Mediterranean, and optimistic in a way.”

Intentionally or not, then, Ennis may be Wright’s darkest project. The architect always carefully planned out how visitors would approach his buildings, but few are as imposing to the viewer as Ennis. “You drive for a ways,” says Breisch. “On these curving roads, up to the canyons, and then you kind of come around a big curve and you’re looking at the other side of the house, from the roadway. It kind of looms in front of you. It is an experience just getting to the house.”

The house is somber in other ways, as well. While the architect’s knowledge of the Mayans was superficial and arguably appropriative, perhaps he knew—he was always careful with the small details—that they typically used their temples as tombs. That built-in mood, more than anything, may explain the success of the Ennis House: It could fit any bill as a location, as long as it was home to monsters, villains, or anti-heroes. Though many kinds of movies and shows used it as a setting, pulpy, genre projects in particular gravitated to its unusual cinematic possibilities.

But just as Wright aestheticized and embellished concrete, experimenting as he went, films and television shows recontextualize the Ennis House for their own purposes, too. As video production technology continues to evolve, the uses of Ennis become even more abstract. Deborah Riley, a production designer on Game of Thrones, has said that the Great Pyramid of Meereen is based on Wright’s textile-block houses. The show’s interior scenes are mainly shot in Belfast, Northern Ireland, but Riley and other designers created sets in the style of Ennis, with help from computer-generated visual effects. And so, for an exterior shot featuring Daenerys Targaryen on a terrace of the pyramid—nowhere near Ennis, but inspired by it—the stone got a once-over in postproduction that turned it into that familiar, patterned concrete. The textile-block houses, in various states of disrepair, live on through the recycling of the ideas they’re built on. Nearly a century in, Ennis house is just getting started.